Wine Chronicles: The Mediocratization of California Fine Wine

By Dan Berger

Article Thumbnail: California’s fine wine industry, once modeled on classic European styles, has shifted toward simpler, sweeter and higher-alcohol wines that appeal to mass-market tastes. Decades of weak wine education and marketing pressures have eroded complexity, leaving many serious wine drinkers to look abroad for authenticity. Sauvignon blanc illustrates the trend with many domestic versions losing the grape’s distinctive character. While some producers still craft ageworthy balanced wines, the broader market reflects what Dan Berger calls the “mediocratization” of fine wine.

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — The standards from which we learn about fine wine emanate largely from Europe.

That is the character of wines I was reared with. When I bought a bottle of Chablis, Puligny or Pouilly-Fuissé in the 1970s, it was dry (as a good chardonnay should be) and had no oak or very little. Alcohols were well under 13%; a few were below 12%. Even the most opulent Montrachets weighed in at 13%; anything higher was seen as an aberration.

It was roughly this way with almost every traditional wine I can think of, including most California versions that came along later. There is no comparison between today’s California versions of the classic European varieties and the originals.

In the intervening decades, California has changed the template and almost never for the better. I believe most of the changes have been for worse; many are aberrations. In the last two decades, I have spent far more money on European wines than on Californian and mainly because of the issue of authenticity — or rather a lack of it.

(And frankly, if the better-quality wines of Canada, Australia and New Zealand were more readily available in this country, my wine-buying assortment would differ even more radically. But that’s a really long story.)

Simplicity sells; complexity is difficult to explain…

This is not to say that California does not produce a lot of great wine. It does and did decades ago. But over time, the number of truly fine varietally and/or regionally interesting wines here that aimed to replicate classic models has declined precipitously. Today what constitutes truly fine domestic wine that even pays lip service to the original models is infinitely small. Most of the real classics are hard to find.

Napa Valley has hundreds of wineries. I believe, obviously cynically, that 80% of them have chosen to tread the path of least resistance because it is the best way to stay alive. And frankly, I cannot criticize them. Wineries have to sell wine to stay in business, so they make wines that appeal to the consumer. And most consumers seem to love wines that are simple.

Because wine education in this country has been so poor over the last four decades, most wine buyers have never been told about wine’s basics. Congress imposed a warning label on all alcoholic beverages in 1988, and at the same time told wineries they were prohibited from encouraging anyone to buy their product – especially if that message was based on scientific research showing specific health benefits of moderate consumption.

As a result, industry-sponsored wine education declined precipitously, leading to the present situation where many consumers don’t know much about wine and don’t care about such incidental details as complexity.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

Today’s wine sales are in the dumpster. Nothing is selling; some believe the industry soon will evaporate. Of course it will not. Wine has been with us for thousands of years, and I believe the current downturn soon will abate and things will be back to normal, probably within a year.

But I believe changes are needed in the styles of many wines. Some suggestions will be made here next week. And because the upcoming harvest poses so many dilemmas, now is a key time for some serious reimagining of what the fine-wine business is really all about and what the future holds.

I wrestled with the idea of tackling this subject because it is so enormous that not only would a book-length discussion be insufficient, but it would take a pliable format to accommodate the frequent (daily?) changes that we may see from area to area, grape to grape, brand to brand.

One U.S. winery has solved many of these problems. The world’s most sophisticated wine company, which now calls itself simply Gallo, probably knows more about wine and especially marketing than just about any other. Gallo’s website says it imports wines from Argentina, Chile, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, South Africa and Spain.

It makes a tremendous amount of wine here, at all price points, marketing them under probably dozens of brand names. It employees some of the most skilled winemakers anywhere. Are most Gallo wines great? Not by a long shot. But Gallo has done massive consumer research, and it offers quality products in a wide range of styles and prices. Most of its wines are good values.

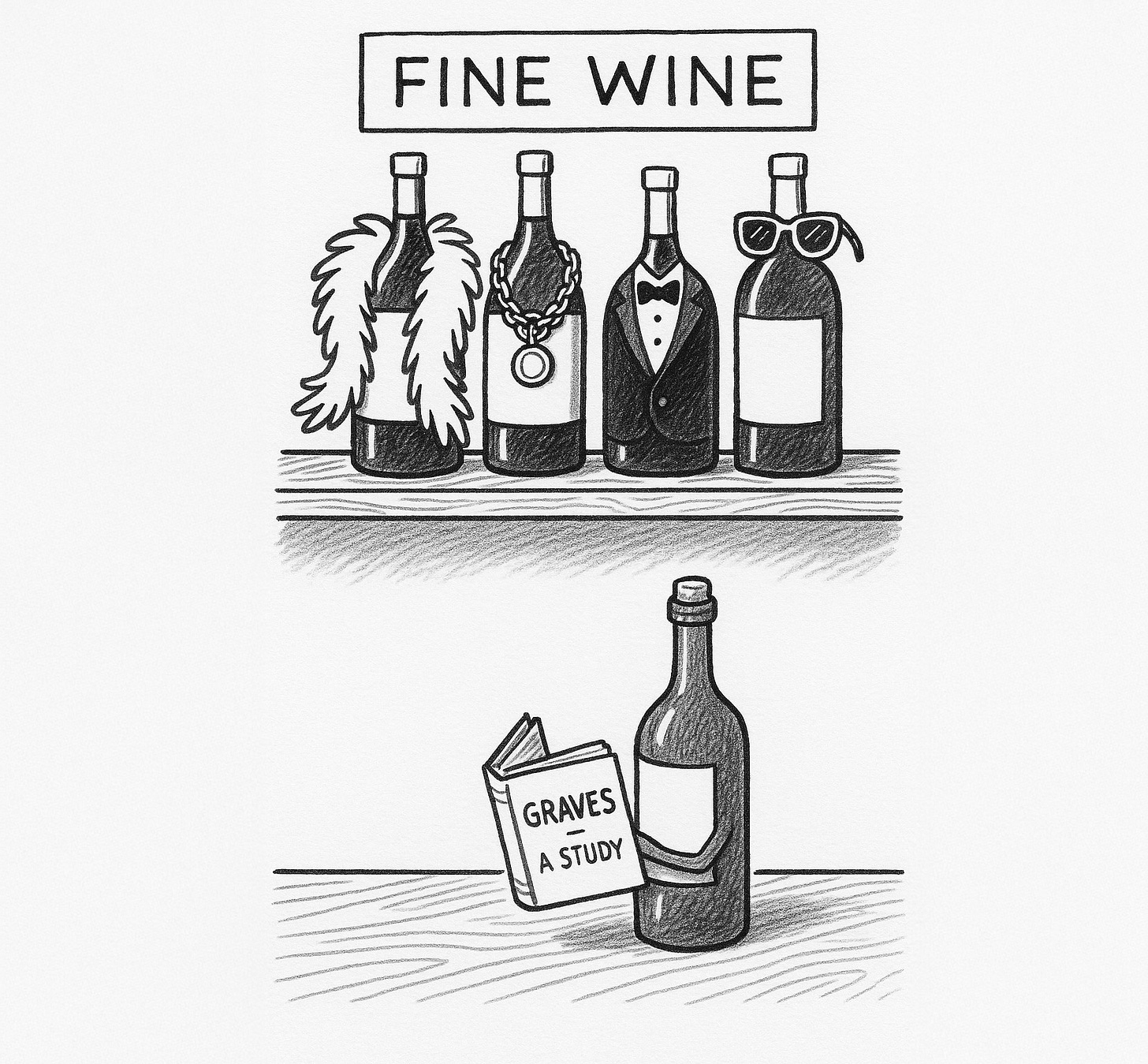

As for “fine wine,” it is almost impossible to define the term. I could name 100 California wines that now sell for outrageous sums, and I would not deign to consume a drop of any of them. I do not consider these to be fine wine. Most are confections, trifles.

The category of “California fine wine” cannot be defined by price. In some ways, the more you pay the less you get. By contrast, European classic wines typically are bought by wine-knowledgeable people who are willing to pay outrageous sums for truly great wine – classic examples of regional personality. High demand for wines of scant production increases their prices.

Many of California’s iconic wines’ prices are set by the producer rather arbitrarily.

Here, any winery that tries to make a fine wine that represents a European model soon is defeated by the notion that it will not sell. Because of the lack of wine education, few Americans know what to look for in a fine wine. Most want to know only the basics, which include: Does it taste any good? And that often comes down to: How sweet is it?

Simplicity sells; complexity is harder to explain and often misunderstood. Without a cultural framework for understanding wine, many buyers view even a $10 bottle as expensive, unaware of the value tied to aging potential or terroir. And today’s wine salespeople rarely have time to teach the nuances — history, place, personality — that define fine wine.

Appreciating a fine wine takes time to savor and absorb it. When was the last time you had dinner that lasted beyond 22 minutes? Most people here eat to live; social media beckons. In Europe, people live to eat; dining is almost a religious experience. Dinnertime dialogue is an endangered species. (The discreet 1981 film “My Dinner with André” was made by a French director, Louis Malle, not an American.)

The best strategy to explain the differences in Old World styles from then to now is by grape variety. We'll start with one grape to illustrate. As will be evident, further examples may be unnecessary.

“The Blanding of Sauvignon Blanc”

One of the world’s greatest grapes originally was one of its least explicable. Decades ago, sauvignon blanc was a newcomer’s challenge. It was green, herbaceous and often displayed idiomatic aromatics such as bell pepper, canned green beans, asparagus and cilantro, and was savory – very dry and the complete antithesis of chardonnay.

Because of this dichotomy, I was mystified, about 1980, when a northern California wine writer bizarrely referred to sauvignon blanc as “poor man’s chardonnay.” Huh? The grapes were diametrically different from one another; you could never mistake one for the other.

Fifteen years later, as the wine columnist for the Los Angeles Times, I wrote a column about what I saw as a growing drawback: Domestic wineries were producing sauvignon blancs that had none of the grape’s endemic aromas. Many SBs were astoundingly neutral.

My column said the grape had been so manipulated that most SBs were stripped of character. The column was sent to my editors. A friend on the copy desk, Greg Sokolowski, wrote the above clever headline. I have used it over the years without giving credit. (Thanks, Greg!)

I cannot be certain, of course, that the “blanding” of all California grapes began about 1990, but it’s a guess. Every grape has good and bad points, and California can still produce some exemplary specimens of varietally precise wines. But we can also screw them up.

Unfortunately, greed has a way of changing the template. I have long argued that the best examples of Eurostyle wine in California come from cooler climates. And most of the great cooler-climate vineyards in California have been ripped out to accommodate faster sales of mediocre wine.

We have lost cooler-climate syrah, zinfandel, gewürztraminer, dry riesling, distinctive cabernet, sauvignon blanc and several brilliant sparkling wine grapes. Those who prefer more classically oriented wine are not being served. To solve the problem, many of these potential California-wine buyers have switched to the European versions.

I realize that most wineries need to make wines that sell to a broad market – the broader the better. And when a winery thinks it might be feasible to scale back the style of wine to more emulate a European model, saner (more marketing-savvy) heads prevail. This happens when someone notes that American wine-buyers buy simplicity.

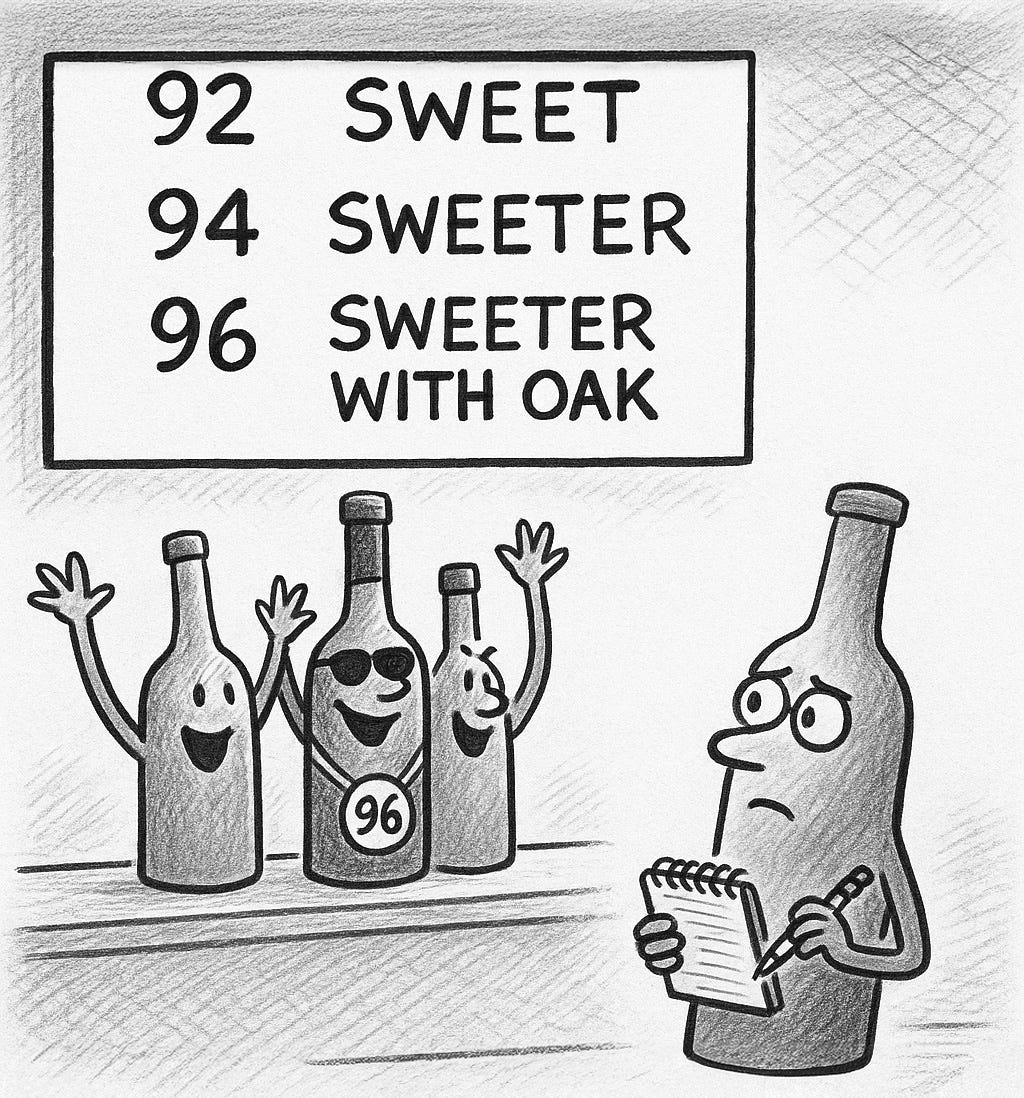

Over time, the U.S. market has consistently rewarded simplicity, while complexity has remained a niche preference. Multifaceted rarely succeeds in the broad market. And the European model is generally about complexity and regional identity and minerality and food-compatibility. Simplicity is what made the 100-point scoring scheme so popular. It is why Americans adopted it with such zeal that it amazed even some of its most ardent skeptics, most of whom later adopted it themselves. (I never did.)

In our primary example, sauvignon blanc, even though the grape variety has in it the seeds of its genetic persona, which includes herbal components, decades ago growers figured out that growing huge crops, removing weak shoots and other vineyard deceits had the effect of dampening the intense varietal aromas that Americans, who knew nothing of the European model, disliked and misunderstood.

One more factor in California’s failure to make distinctive SBs is high alcohol. The best sauvignon blancs I have tasted in the last 25 years are all about 13.% alcohol, with some less than that. This is not a coincidence. Too much alcohol gives the wine the impression of sweetness, and when that is added to low acidity and actual residual sugar, the result can be unappealing. Far too many domestic SBs weigh in at 14% or more.

About the same time that most California SB was becoming more alcoholic and simpler, New Zealand began importing SBs to the United States that were initially considered odd because they smelled more like passionfruit, gooseberries, ripe asparagus, cat pee (!) and one other trait that was most appreciated by American wine buyers: sugar.

New Zealand is a unique spot in the wine world. It has two competing grapevine challenges. It is relentlessly cold and, in most locations, like on the South Island, stiff ocean winds from both east and west slow photosynthesis, exacerbating green elements. Cold and wind also keep acid levels high.

To make the tart wines approachable, a trace of residual sugar often was left in the wines. Then a few cagey New Zealanders figured out that a “trace” of sugar could well be expanded to heaps – and most Americans wouldn’t complain.

The huge success of New Zealand SB in the U.S. market did not go unnoticed by American SB makers. Most began competing with NZ by making their SBs sweeter. There was one problem with this strategy: The domestic SBs didn’t have the acidity that the New Zealand wines had and that were better balanced.

(A few California producers understood that it was important for sauvignon blanc to be balanced. One place where it began to show enough distinctiveness to deliver real varietal character was in the Russian River Valley. Then quality producers from Lake County and then Napa Valley chimed in with more interesting SBs that actually developed nicely with some bottle age. And probably the most classic sauvignon blancs produced in California had always come from Sonoma County’s Dry Creek Valley.)

Though some quality-oriented producers understood how to make fine wine from SB, most volume brands, guided by marketing-desk mentality that required the wines to be sweet, dominated the market.

The result was a lot of bland, uninteresting sauvignon blancs that had only one attribute: They were too sweet. Even in Napa, a few holdouts still make SBs that have insufficient acidity and/or high alcohol and/or excessive oak to be called fine wine. Many Napa sauvignon blancs are drunk as soon as they are released. Often, they are served ice cold. Many Americans think of this grape as a drink-instantly product, which I consider sad.

Sauvignon blanc can age. And often gorgeously. One of the best examples is from Spottswoode Winery in St. Helena. Over the years, I have had several of their sauvignon blancs that averaged in age from six to 12 years. I’ve always found them exemplary.

What’s most appealing about the Spottswoode SBs is that they are fashioned like Graves of Bordeaux, many of which have a reputation for aging gorgeously. Part of that is because most white Bordeaux have a good portion of semillon, but it’s the sauvignon that comes though as the wines develop.

The current Spottswoode SB release is $48 a bottle. In 2017, the Novak family at Spottswoode released a tiny quantity of an estate SB from a 1.07-acre parcel called Mary’s Block, available only to club members. I have not tasted it.

Readers might ask, “Has the ‘Cal/NZ/SB/sugar/alcohol/oak’ formula impacted the wines of Europe?” I am not being coy when I say yes and no. Mostly no, but maybe yes in a few cases.

The European model for classic sauvignon blanc is the eastern Loire Valley, notably Sancerre and its nearby second-cousin, Pouilly-Fumé. Using the word “classic” to define them includes the notion that they are seriously dry, which includes good acidity, lower pH, distinct minerality and alcohol levels in the 12% range. The best of these sell for a lot more than New Zealand SB but nowhere near as expensive as white Burgundy, of course. And the Loire’s crème de la crème age phenomenally.

Generally speaking, the best Loire Valley stars always have flown well under the radar among West Coast buyers. On the eastern seaboard, as well as in Chicago and a few other major cities, Loire Valley SBs have always sold well.

In the last 20 years or so I have noticed a greater interest in these wines by California wine-buyers. I cannot explain how this has occurred, but it may be related to the fact that sauvignon blanc wine-lovers have finally discovered the eastern Loire Valley.

But not every such wine is a winner. One way to assess the quality of a Sancerre or Pouilly-Fumé is to check to see what the alcohol level is. If the label says 13.5%, I would be wary. A point lower is likely to be more reliable.

As for many lower-priced domestic sauvignon blancs, I continued to find a dispiriting vapidness to many of them. I believe they are being made that way because marketing people think simplicity sells and complexity calls for explanations – and Americans don’t have time for or interest in such folderol.

At this point, I could shift gears and discuss several other grape varieties and how they have been forcibly distorted away from classic European models. Instead, next week I will look at how California might restrategize to solve a problem it has created that has led to wine sales stagnation – and what I call the mediocratization of most commercial, widely distributed California wines.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Wine Discovery:

2021 Matthiasson Cabernet Sauvignon, Napa Valley ($85) – There is absolutely nothing mediocre or “modern” (in the worst sense of the word) about this classic, 1970s style of cabernet that shows in several ways why it is one of the Napa Valley’s most perfectly crafted cabernets that is respectful of the region’s heritage. Using fruit from various areas in the valley, Steve Matthiasson designed this wine with early drinkability in mind but potential to improve for 10-15 years. When it was tasted blind by a Sonoma County winemaker a week ago, he declared it to be “pure silk,” explaining that it was superbly made to emphasize a perfect equilibrium between the acidity (so the wine could match with food) and significantly lower tannins than many “bigger” cabernets display. It was crisp without being bitter. The website says, “For complexity and balance, it is composed of fruit from eight State Farm vineyards throughout Napa Valley,” including cooler Coombsville, herbal Rutherford, richer Calistoga, freshness and minerality from Mount Veeder and soft fruit from Oak Knoll. Two industry veterans both liked the structure of the wine based on moderate alcohol (only 12.5%!). Several hours later, with food, the additional aeration had made the wine even more dramatic but in a subtle way. There’s little that’s ostentatious about this exemplary wine. But it’s a gem. — Dan Berger.

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is C: "Failure of grapes to develop."

“Coulure” refers to a viticultural condition where grape flowers fail to develop into berries, often due to cold, wet or cloudy weather during flowering. This results in reduced yields and uneven clusters, posing challenges for growers focused on quantity and consistency.

The word comes from the French verb couler, meaning “to flow” or “to run,” referencing how the unpollinated flowers drop from the vine. Its usage in viticulture dates to at least the 18th century in French wine-growing regions.

While often unwelcome, coulure isn’t always devastating. Lower berry counts can occasionally concentrate flavors in the remaining grapes, producing wines of greater intensity and character. In this way, coulure reminds growers and winemakers that nature’s imperfections sometimes lead to unexpected strengths in the glass.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.

The loss of style and sense of place is tragic. Here are excerpts from a blog I wrote in 2022, with a link to the blog below.

“Having followed the evolution of the California wine industry since 1972, I’ve seen many changes in winemaking styles to appeal to new markets and critics whose rankings drive sales. In the past two decades, one trend is for the higher-priced, higher-scoring California cult wines to be very similar in style – big extract, thick, high-alcohol fruit bombs that lack any sense of place.”

“I was reminded of this recently in reading through various pitches from on-line wine merchants hyping their higher-priced spreads. Here are a few excerpts:

- “Deep color, super-ripe; explosive bouquet; deeply buried tannins; deep, dark and muscular; bombastic youthful richness; explosive aromas; very full-bodied and dense; a show-off style Cabernet! (Explosive aromas); muscular, hefty mouthfeel; deep color, super-ripe and imbued with lots of chewy, chocolate-y tannin; California Power Juice; this red takes no prisoners (nose of unsmoked cigar tobacco, pen ink blackberries).

“Sound appealing? Lots of explosions on the palate, and over-the-top, one-dimensional tongue-gripping wines that can be fatiguing and woefully difficult to match with cuisine of any kind.” More:

https://sandiegowineguru.com/beyond-the-california-cult-fruit-bombs-classic-wines-from-napa/

Happy to read you mentioned Spottswoode as a top notch SB. In my (inexpert) opinion, it’s the best on the market. Getting your hands on a bottle, however….