NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — As California vineyard temperatures inexorably rise, some wine grapes that grow in once-temperate climates may be unable to reproduce similar wine characteristics that emulate past vintages because of these increases. As a result, the style of some wines may change noticeably, which might have a negative impact on wineries that have long made certain wines that they want to display as a house style. Solving the problem of increasing temperatures includes the search for cooler vineyards.

Some grapes have long been identified as preferring cooler climates, such as gewürztraminer, riesling, Grüner Veltliner and pinot noir. Efforts to grow them in warmer regions have usually resulted in mere curiosities and occasionally utter failures.

Several other grapes prefer cooler climates but may be grown satisfactorily in moderate-climate areas and still produce good wines. Among the varieties that prefer cool regions are semi-aromatic grapes (such as pinot gris, viognier, vermentino, arneis, and albariño) as well as pinot blanc, chardonnay, grenache blanc and sauvignon blanc.

As vineyard temperatures increase, most of these varieties will continue to produce satisfactory wines, although styles might change over time. Some aromatics may shift from minerally, citrus and tropical fruit to more richly endowed scents such as peach, apricot and honey. And alcohols may increase.

One important strategy for wineries seeking to avoid higher alcohols is to investigate the removal of alcohol. Technologies now exist to permit alcohol removal in various sophisticated ways that actually improve the aromatics of the wines and create better harmonies and balance. Even some European regions that have always delivered wines with racy acidity and minerality might have a hard time trying to coax those elements out of their terroirs.

(Side note: Importers and fine wine shops have long told me that their best buyers of French, German and Italian wines are winemakers!)

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

To address this problem of changing aromatics as temperatures increase, wine scientists suggest that it might be a good idea for growers to plant grape varieties in cooler locations. There are several ways to define exactly what a cool climate is. No single definition is universally accepted.

I asked Don Neel, one of California’s most thoughtful grapevine authorities, his definition of cool-climate viticulture. For more than three decades, Neel has been publisher/editor of Practical Winery and Vineyard Magazine.

“You’ve entered into a fabulous subject,” Neel said, “but you really can’t do it in one article.”

After giving me several examples of cool-climate wine areas, Neel implied that the subject was so large that it might take a book or even two.

“Certainly, Oregon is a cool climate, as is upstate New York, of course all of New Zealand … and Anderson Valley in Mendocino County, and higher altitudes like Colorado and parts of Lake County. But in California, Anderson Valley is one of the better examples of a cool climate wine-growing, although it has had some climate variation over the last five to 10 years.”

Neel also talked about cool climates being related to the number of days from bud burst through veraison (fruit coloring on the vine).

Some formerly cool regions now may not be as cool because they are areas “prone to heat events late in the growing season, as late as October.”

Also, trying to define a cool climate for grape-growing should not be confused with “cold-climate” regions. The differences are significant. Petaluma-based winemaker/wine consultant Clark Smith said he defines a cold climate as one where winter temperatures are so cold that vinifera grapes (French varieties) cannot survive. In some cold climates vinifera grapevines die. In those locations specialty hybrid grapes today make some excellent wines.

Defining a cool climate is a rather complex subject, one that has intrigued winemakers and winegrowers around the world for more than a decade. Next Jan. 26–28, the 11th International Cool Climate Wine Symposium will be staged in Christchurch, New Zealand.

I once wrote that Australia’s Clare Valley was a cool region even though daytime temperatures can be excessive. A year later I visited the Clare Valley and took a vineyard walk with a grower. The temperature was well over 90 as we walked up a rise. It was about 3:45 p.m., and the grower asked me where my jacket was.

“In this heat?” I asked.

“You’re going to need it, mate,” he said.

By 4:15 p.m. the temperature had dropped by roughly 20 degrees. and by 4:30 the wind had kicked up and the temperature had dropped into the 40s. The grower said nighttime temperatures in Clare were cold year-round.

Decades ago, one of the coolest regions in Sonoma County that grew pinot noir was the southwestern tip of the Russian River Valley around the village of Freestone. Vineyards there were so close to the Pacific Ocean that marine influences slowed down grape maturation to a crawl. Ripening grapes there as recently as 2006 was daunting; only adventuresome growers risked it.

Today another cool region for chardonnay and pinot noir is the Petaluma Gap, which was certified as an American Viticultural Area in 2017. It runs from Bodega Bay on the coast and includes a wine-defined area as far east and south as San Pablo Bay at Sears Point.

But it isn’t so much the cooler temperatures in the gap that affect the vines as it is the wind. Constant winds from the Pacific Ocean reduce the rate of grapevine photosynthesis, creating a slow, measured and long maturation. Grapes remain on the vine a little longer, developing additional flavors. Wines made in the Petaluma Gap are some of the best in California.

But cooler temperatures and wind are not the only conditions that define a cooler climate.

David Strada, who was once in charge of marketing New Zealand wines throughout the United States, knows about cool-climate grape-growing. He suggests that cool climates can include places where daytime temperatures rise significantly, but where the diurnal differences (the day-night swings) are radical, such as 50 degrees or even more.

“Diurnal differences can be important, but no matter the size of the difference, the evening temperature also has to be low enough to make a difference,” Strada told me. “In some areas, it gets so hot during the day that vines actually shut down.”

He adds, “In New Zealand … I think high and low temperatures have to be considered at each stage of the growing season … Low temperatures can lead to a sluggish start. Every year it seems that New Zealand has a heat spike in late January or early February. But it rarely goes above the high 80s and usually lasts only a day or two. Compare that to California or Spain or Portugal.”

All of New Zealand is a cool-climate – on the North Island (such as at Hawkes Bay and at Martinborough to the south) and on the South Island, where several unique wine-growing areas are cooled by three massive water sources: the southern Pacific Ocean, the Tasman Sea and the Antarctic Ocean.

Because New Zealand is relatively small and has oceans completely surrounding both islands, marine influences, including significant wind, are a constant feature. I have experienced strong winds on both islands. The constant east-west winds are why cabernet sauvignon is rare in New Zealand. The grape really calls for warmer growing conditions, such as in Napa Valley.

However, within the last 20 years cabernet from New Zealand has become quite an “in” purchase for wine-lovers. Arguably the best New Zealand cabernet is from Te Mata Winery in Hawkes Bay, whose fabulous Coleraine sells out every year. The scant number of Coleraine bottles that make it here sell for more than $70 a bottle.

Napa’s valley floor vineyards rarely have enough cooling to provide the conditions that once existed annually and that allowed for production of more balanced red wines that were made decades ago. Some of that, however, might very well be a choice of winery owners and winemakers to harvest later.

Though vineyard temperatures inevitably will rise, there are several strategies that could be employed by some wineries to create slightly cooler wine-growing than now exists. Some of these techniques may entail more expense and may not seem to be worth exploring, but those with enough funding could find some of these strategies to be worth pursuing.

Canopy Management

Richard Smart, who passed away in early July in his native Australia, was considered the world’s greatest viticultural expert specializing in managing the canopy of leaves that help to protect grapes from direct sunlight – a critical aspect of protecting fruit from excessive sun exposure that can cause sunburn that alters flavors.

Too much direct sun also can negatively affect the acid and pH balance of the resulting wines. There are in-winery ways to make wines that avoid some of the negative aspects of sun exposure, but many of these tactics are considered to be just a way to salvage growing errors, a way to solve a problem. A better idea is to grow grapes more carefully with less sun exposure.

One way is to retrofit the canopy to provide increased foliage, which provides better shading of the fruit. Experts in canopy management say grapes must be protected better than some of the trellising systems now employed are doing. In many trellises today, creating a significantly larger canopy of leaves creates more dappled sunlight on grapes. Additionally, temperatures inside a managed canopy are a little cooler during the hottest days, protecting grapes better than open (minimal leaf) trellis systems.

Neel also said, “One idea that has been used with some success is putting up shade cloths to block the sun. It has been used in several areas and seems to work well.”

Another idea that has been employed in some older vineyards is to use overhead sprinkler systems. Overhead sprinklers (an older form of irrigation that has largely been replaced over the last 50 years with drip irrigation) can be used during the hottest days to irrigate at a time when the plants need a drink and also to help cool the grapes and reduce the possibility of dehydration.

Overhead sprinklers have drawbacks. They use enormous amounts of water, which is not only expensive, but water is a precious resource. After the development of the more economical and environmentally sensitive drip irrigation systems, overhead irrigation was far less employed. Few wineries today use them.

Misting

In the mid-2000s, Beaulieu Vineyard in Rutherford began a multifaceted vineyard trial conducted by Mark Greenspan, founder and president of Advanced Viticulture Inc. It investigated the use of misting technology to spray tiny droplets of water/mist above and under leaf canopies to see if the technique cooled vines and/or grapes. And if it did, was it beneficial for wine quality?

The control group (vines that were not cooled) produced wines with higher tannins and lower acids. Meanwhile, misting over the vine and inside the canopy separately produced cooler fruit and seemed to benefit wine quality. Both misting methods had benefits and drawbacks.

However, it remains to be seen if overall wine quality using misting significantly improved the resulting wines.

In his concluding remarks in his report on the promising misting strategy, published in a 2009 issue of Wine Business Monthly, Greenspan wrote, “…the preliminary results of this trial indicate the cooling power effectiveness of a [misting] system that uses a tiny fraction of the water of a conventional impact sprinkler system. Sounds pretty cool to me!”

Higher Elevations

Worldwide, higher-altitude vineyards are almost always associated with cooler growing conditions. Also, occasionally higher elevations have better drainage. It is generally assumed that higher-altitude properties are at least 500 feet above sea level, but there is no consensus here. Some growers tell me that high altitude starts at 1,200 feet. One Columbia Valley grower (Washington) told me it started at 1,500 feet. And many people in Colorado simply laugh at those estimates because most Colorado vineyards are close to 2,000 feet and usually well above that.

Higher elevations tend to be cool because of several conditions that do not exist in most valley floor vineyards. Among the differences at altitude: Ultraviolet light is greater, soils are thinner (better for drainage), diurnal temperature fluctuations tend to be greater, humidity levels are typically much lower (reducing chances of rot) and ground temperatures tend to drop more rapidly because of wind.

However, several problems exist with high-altitude grape-growing, which can be much more expensive than growing fruit in flat land. For one thing, vineyards in high altitudes rarely are contiguous, so they can be harder to farm; most are small patches that must avoid erratic terrains, rocks, rills and improper soils and which may be impacted by trees and bushes that need to be removed. There is also the problem of irrigation of young vines until they are fully established, which means trucking water up long trails on barely paved (or unpaved) roads.

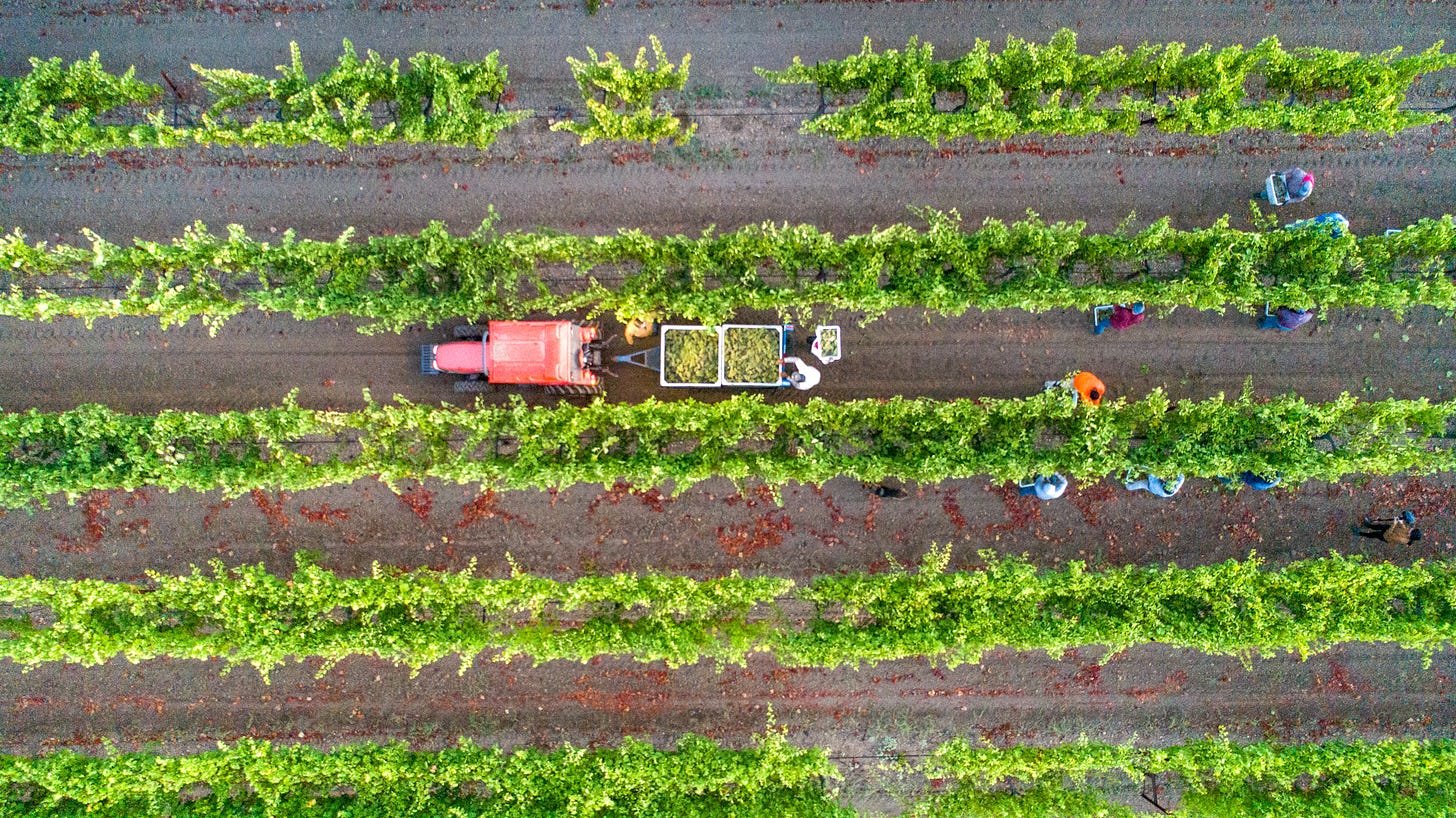

It is also harder to get labor into remote mountain vineyards for the installation of vines with end posts and wires, installing irrigation systems, and dealing with harvesting of fruit and long drive times to wineries.

Also, thinner soils usually are well-drained, which is either good or bad, depending on the grape varieties selected, the age of the vines and other conditions that are unique to higher-altitude vineyards.

The nation’s highest-altitude vineyard is Colorado’s Terror Creek Winery, which overlooks the North Fork Valley at the Gunnison River. It sits at 6,400 feet and produces one of the greatest gewürztraminers I ever tasted.

Climate Zones

UC Davis has long used a five-level index to speak of temperature zones. Regardless of where a vineyard is planted, it is vital for grape-growers to know exactly what kind of climatic zone they are planting in and how to trellis it and farm it both before and after the vines are established. Pre-planning is essential.

According to a 2021 UC Davis press release, the Winkler Index was created in the 1940s by A.J. Winkler and Maynard Amerine. Using rudimentary climate data from U.S. Geological Survey maps (which was the only data available to them at the time), the Davis professors “calculated average daily temperatures to identify five climate regions, from coolest (Region I) to warmest (Region V).”

Some 80 years later, it is obvious that much has changed. For one thing, the Winkler Index did not look at the crucial statistics regarding diurnal temperature swings. Nor did it take into account the length of time that a particular temperature was reached at either its height or its lowest point. That data later was known to be critical for understanding a particular region’s real climate zone.

Starting in 2020, with major funding from Warren Winiarski, founder of the famed Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, a team of researchers at UC Davis began to revise the Winkler Scale . In a news release on the project in 2021, UC Davis said a new climate index was needed because of “climate change, rising temperatures and erratic weather that comes with it, [which] has already limited the accuracy of these regional classifications.

“Napa Valley, for example, was considered Region II [slightly cool to moderate] when the Winkler Index was developed. Now, most parts [of Napa] are a Region III or IV. UC Davis students are [recalculating the scale] … to create a visual tool to show the movement of California’s viticultural regions through the classifications over time.”

Winiarski was quoted in the press release to say: “The development of new methods of measurement would be extraordinarily helpful. With better knowledge of changes in the compositional elements in the grapes … we’ll have better guidance on how to respond in the winery and create the wines we want to make.”

(The project funding link is caes.ucdavis.edu/news/taking-climate-change-vineyards.)

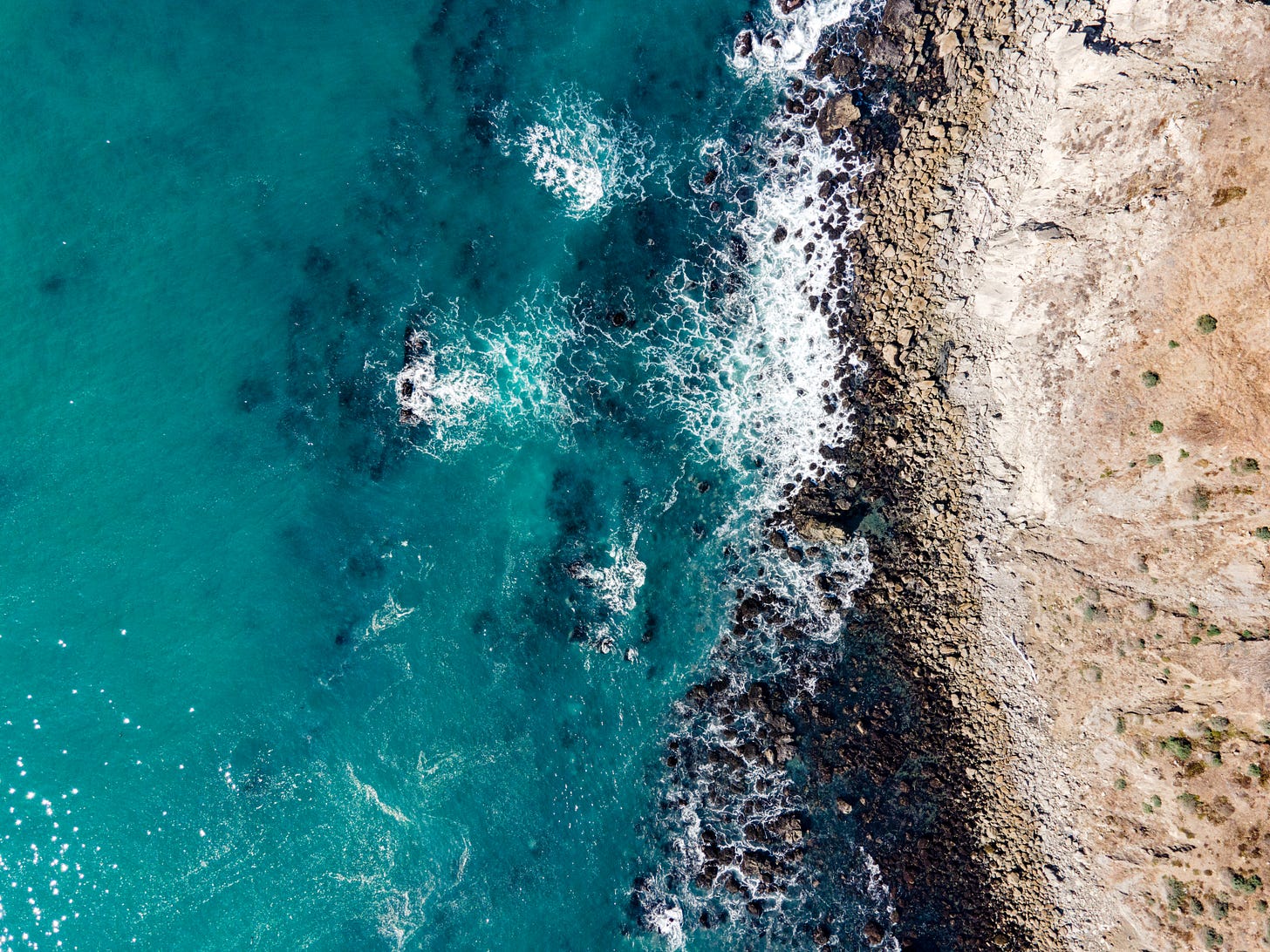

Planting Near Water

Common knowledge in the past about the development of wine regions for making fine wine said that it is best to plant vines near a large body of water. This has been true in many of the world’s greatest fine-wine areas.

Most wine authorities agree that California’s best vineyards are coastal. Oregon has both coastal and waterway influences. Washington is cooled by the vast (1,200-mile long) Columbia River as well as the Snake River, which also benefits the wine country of Idaho. Michigan’s twin upper peninsulas are adjacent to the Great Lakes. New York’s small and large Finger Lakes allow for production of exceptional wines. Germany boasts gorgeous, historic waterways whose river banks are dotted with dozens of wineries. Bordeaux’s large and lengthy (330-mile) Garonne River (which has 25 tributaries) provides remarkable cooling to hundreds of châteaux.

There are many exceptions to the “plant near water” strategy, such as high-altitude vineyards. But if growers are seeking to find cooling influences away from their own regions, planting near large water sources is certainly a valid stratagem.

Cool Climate Clones

Research into various clones of grape varieties has been one of the most fascinating and yet least discussed aspects of growing grapes. Many pinot noir lovers now can talk about the different clones of pinot noir that have been widely planted in the state. Some pinot-lovers say each clone has a unique expression of either aroma or taste. But not all winemakers agree, saying that other factors are at play.

Among the most popular pinot noir clones are Swan, 115/667, Pommard, Wrotham, Mount Eden, Calera, 777 and Martini. And dozens more. Despite general agreement about what characteristics the most widely planted clones deliver, disputes have arisen about what particular clones produce. Some winemakers believe that the site (terroir), the date of harvest and the volume harvested all make far more distinctive statements than do the clones.

However, it is known that some clones for chardonnay, cabernet and other grapes do better in warmer climates. As vineyard temperatures increase, it may be vital to look at various clones of all grapes to determine which clones do best in increasing heat. And Neel also pointed out that recent work into the clones of grenache and syrah have noted differences that may affect how they grow in different climates.

Final Thoughts

Just about every year, grape-growers and wineries face daunting problems that the public will never hear about. It might be a new vine malady (such as a viral infection like red blotch disease), a fermentation aberration, or problem with barrels, bottles, corks, capsules, hoses or trucks.

It all makes for a business model that calls for far more intense problem-solving than any wine consumer could ever imagine. As a result, unpredictable weather issues are just another one of the challenges that winemakers and grape-growers face now and will in the future.

One of the key points is that each individual property has a unique footprint and faces unique confrontations. One reason that many regions of California today face daunting environmental challenges is that their initial decisions may have been made hastily and/or frugally, without expert advice.

One such decision might have been to choose a trellising system without knowledgeable counsel from someone like Smart, who admittedly was expensive but rarely was incorrect. Those who planted vineyards in the last 40 years without professional expertise now may be facing issues beyond simply increasing temperatures.

At the very least, climate change will require many wineries to consider retrofitting their vineyards to create more shading of their fruit to mitigate the negative effects of additional temperatures brought on by direct sunlight on their grapes. All of this does require capital expenditures.

However, the main problem today is that wine sales nationally and internationally are extremely slow, putting enormous pressure on winery revenues. So although now or soon is probably a good time to deal with vineyard redesign, the cost of correcting past errors and planning for future heat-related problems is daunting — especially with wine shelves bursting with competing wines that are being sold at deep discounts.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Wine Discovery:

2023 Saintsbury Mencia, Mendocino County, Alder Springs Vineyard ($38) – Napa Valley pioneering winery Saintsbury has long been recognized for its excellent pinot noirs as well as chardonnays, but the winery recently embarked on an exploration focused on different varieties and fascinating production techniques. This project, called Footnotes, is a classic example of winemaker Tim Colla’s creativity. The website tells part of the story: “Spain's Mencia grape was popularized by the Ribeira Sacra DO, where pitchy, brightly fruited reds are quaffable yet complex. While it is rarely seen in the United States, Colla happened upon some fledgling vines on a recent vineyard walk with grower Stuart Bewley at Alder Springs in Mendocino. When Tim giddily inquired about the grapes, Stuart replied ‘They're for you, Tim.’ Our first ever bottling of Mencia is an exploration of this rare fruit, which somewhat resembles our beloved Pinot Noir. Somewhere between the delicacy of Burgundy and the rustic spice of Rhône Syrah, the first Saintsbury Mencia vintage won't be around for long. Tasting notes: Pure, pitchy red currant fruit on the palate with a floral nose. Savory, pencil-lead minerality adds tension and spice to balance juicy freshness.”

I found the wine structurally fascinating because its alcohol is only 12%, and this makes the mouthfeel similar to the Austrian grape zweigelt with its slight angularity that works well with foods such as grilled sausages. The flavors resemble a crisp gamay grown in a cool climate. Best served very cool. - Dan Berger

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is C: "Caused by upward-moving wind."

"Anabatic" refers to winds that rise up slopes or mountainsides, typically during the day when the sun heats the terrain. In viticulture, such winds influence temperature regulation and grapevine development, especially in hillside or mountainous vineyards. These upslope breezes can moderate heat, enhance air circulation and help reduce fungal pressure — all beneficial in a warming climate like Napa's.

The term "anabatic" derives from the Greek word anabainein, meaning "to go up." It entered meteorological and geographic use in the early 20th century and has since found relevance in agriculture and viticulture. Understanding local wind patterns, including anabatic flows, is key to site selection and canopy management, helping growers adapt to increasingly volatile climate conditions.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.

You need to write about why the industry is suffering with no tourists because California is too expensive and the Governor has failed ! This Governor is killing this State and family businesses are going under and Newsom is off in La La Land with supporting those from not America. Just drive down Hwy 29 .. ghost towns and no one on the road all the way up to Calistoga.