NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — I cannot tell you the number of times a skilled winemaker, someone who spent years taking courses in chemistry and microbiology, who worked in menial jobs cleaning wine barrels and hauling hoses and finally made it to the big time making fine wine, has said to me roughly the same thing:

“Making wine is great. Selling it is a nightmare.” Or words to that effect, often without any gentility and usually with a slightly bitter tone.

Selling wine is not most winemakers’ strong suit; many hate it. Some adapt to its necessity, but trying to understand the marketing of wine, as with any consumer good, has little if anything to do with crafting a fine vintage that theoretically adheres to the personality of the site, the aspirations of the vine and the temperament of Mother Nature in that particular year.

These dilemmas have nothing to do with what various marketplaces demand. Over the decades I have gotten to know three winemakers who dreaded the requirement that they face potential buyers, whether wholesale, retail or consumer. All three men avoided the task industriously.

Operating a winery is not a great idea today. Costs continue to rise and profits are more difficult to achieve.

One hired a public relations company to deal with it; a hired gun ultimately handled every public appearance in which the winemaker would normally be visible. The second winemaker declined all public appearances; on the occasions when he was required to be in attendance, his wife mounted the podium. The third, who was probably agoraphobic, was hired by a huge wine company, where he could hide out at the winery and make wine. He rarely left; his name was never mentioned outside headquarters.

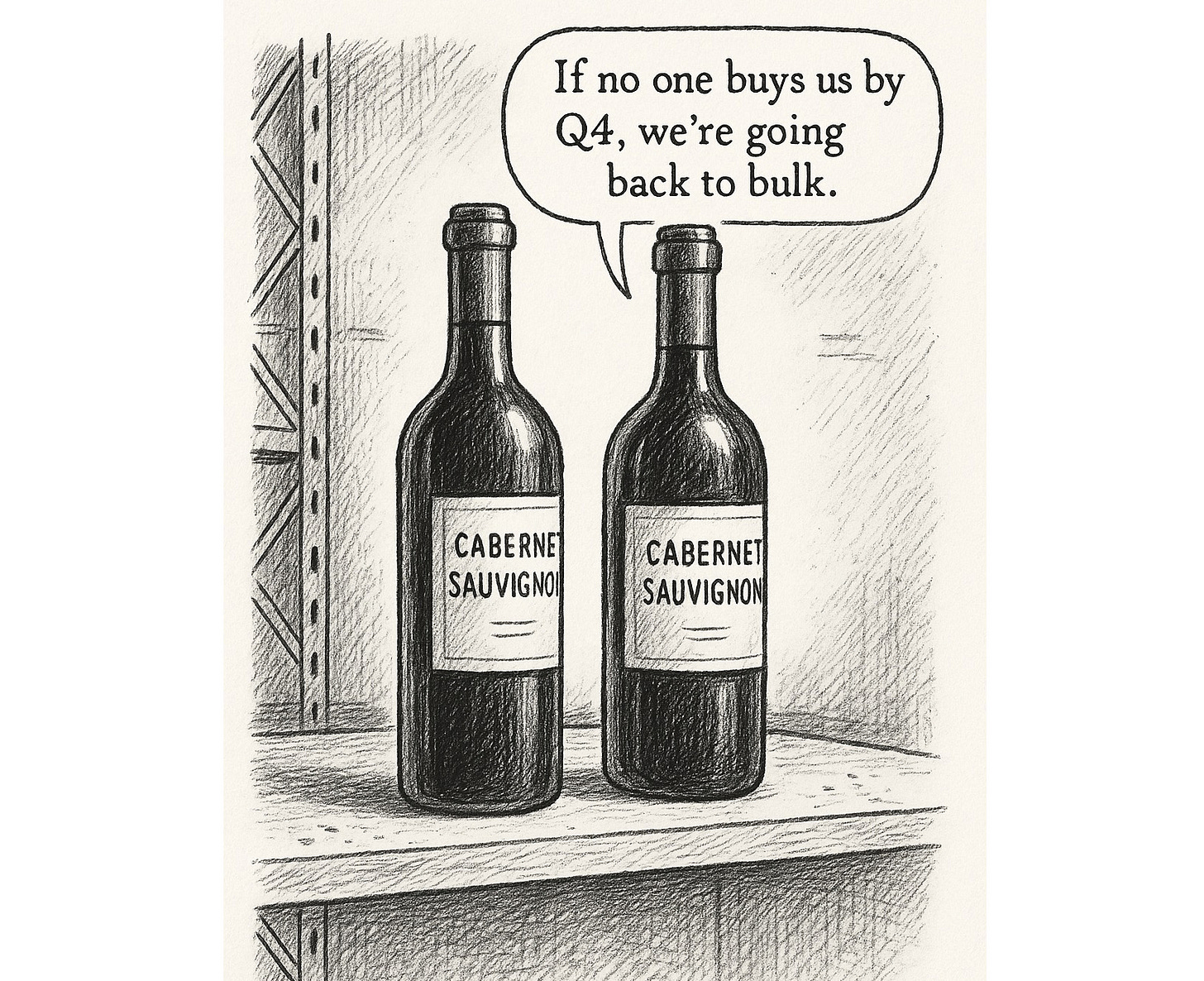

The topic of the last couple of years is that wine isn’t selling. I was chatting with seven younger wine-marketing people two weeks ago. The topic was chardonnay and what constituted quality. The discussion could’ve lasted months. We had only two hours.

After listening to the assembled younger folks (none above age 35), one thing I said surprised them: The current sales austerity we now face has been with us before and will be with us again. There is virtually nothing new, except that today’s situation is worse than I have ever seen it.

And no one has a solution. The fact that it is worse than ever makes it seem as if it is going to be with us forever. And it may well be for a long time. In three industry wine seminars over the last three months, three “marketing experts” (I assume they were; they were keynote speakers) gave several differing opinions about where this is going. Each drew roughly the same conclusion: “I don’t know.” Thank you. Still, there is a reason for some optimism.

But pessimistically, operating a winery is not a great idea today. Costs continue to rise and profits are more difficult to achieve. Just look at what is happening with one of the world’s largest wine companies, which will soon deflate in size.

Duckhorn, a Napa Valley-based success story, is retrenching. Constellation Brands said recently that it was downsizing its wine footprint and selling various wine brands that include Meiomi, Woodbridge, Robert Mondavi Private Selection (not the Mondavi Oakville empire), Simi Winery, 6,600 acres of vineyard land and two lesser wine brands. The buyer was Livermore-based The Wine Group.

Then recently, Republic National Distributing Co. – the nation’s second-largest wine wholesaler – said it would leave California, leaving in limbo several dozen small wineries without any distribution assistance in the state.

If behemoth wine companies see the handwriting, you know their downsizing decision are not surprising or made without good reason, given the past financial success of the companies. People who follow financial markets closely might remember that a company called Canandaigua (the name the company had before it was Constellation Brands) has always been an incredibly successful financial company.

In the mid 1980s, when wine was only a small portion of its business Canandaigua was hugely successful, and its ascension into fine wine included the purchase of the great Mondavi Winery in a deal reportedly worth $1.03 billion. Then in 2015 Constellation paid a reported $315 million to Joe Wagner for his Meiomi brand.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

That was only 10 years ago. A lot has changed since then. To begin with, many people have decreased their alcohol intake or stopped drinking altogether for health reasons.

Another factor is American consumers have switched their allegiances from traditional wine to beverages with lower alcohol levels. Many Americans are shifting away from traditional table wines, Napa’s stock in trade. Many now see it to be too alcoholic.

Just look at the label for just about any upscale California red wine. You will see that the alcohol listed is 14.5% or more. Compare this with typical German rieslings that usually weigh in at less than 12%. (I find it surprising that as California wine declines in sales, there has not been a commensurate increase in riesling interest.)

It has been about two years since Americans began to seek lower-alcoholic beverages. Many have switched to low- or no-alcohol wines and several other products, such as ciders and hard seltzers. Consumers seeking traditional California wines are finding that most of those that are on the market today were made two or three years ago.

Most white wines made in 2023 and red wines made in 2022 or earlier all conformed to the standard model in which alcohol levels were a product of grapevines that had been grown for table wine since the 1960s to be slightly higher than average wine consumers desired in 2024 and beyond.

To begin making lower-alcohol table wines that are attractive to today’s consumers, some vineyard retrofitting might have to be done, and to take effect efficiently may require additional time. Not only will vine-trellising come into purview, but some vineyards may need to pull vines out and replace rootstocks.

That’s not all. There is also the bottleneck that has occurred in the wholesale tier of wine distribution. Meininger’s International had a recent article about jockeying for dominance among wholesalers.

The articled started: “Wholesalers are still scrambling to line up the biggest [wine] producers, even if they have to poach them from someone else. And they continue to drop all but the largest wineries [from their portfolios], leaving any number of established brands – but which aren’t quite big enough, even if they make 200,000 cases – looking for a new distributor.

The greater the consolidation in the wholesale tier of wine distribution the more wholesalers will seek to reduce inventories, in many cases dropping wineries altogether.

It has long been known that wholesalers can hardly do the job of wine marketing (or merchandising) on behalf of all of their smaller brands. Until 20 or so years ago, many large wholesalers had enormous portfolios that included smaller brands.

To represent their smaller brands, especially in major wine markets such as Los Angeles and San Francisco, wholesale companies used to employ wine specialists who knew their small brands in detail and were able to speak cogently about why these wines were selling for as much as they were.

In the last decade, many wholesale companies have focused more heavily on the sale of spirits, which make infinitely more money for them. As a result, dozens of fine-wine specialists have been laid off or reassigned. Several wholesale wine specialists I know tell me that wine sales have suffered as a result of wholesale companies retaining spirits specialists and firing those who specialize in wine.

As wineries lose representation in both retail and restaurant sectors, many have investigated what it costs to hire their own salespeople for major markets. What they usually discover is that it is far too expensive. And wine sales throughout the country are required by law to be conducted through wholesalers. The mandatory three-tier system makes selling wine complicated for smaller wineries.

If a winery is dropped by its wholesaler, one key thing that it loses is access to warehousing and trucking. Also costly is gaining approval to ship wine into other states. Each state has its own alcoholic beverage requirements. What might be a requirement in Nebraska could be different from what’s required in Massachusetts.

And to complicate matters even further, the licensing fees to sell in each state can be prohibitive. And there are 51 jurisdictions that must be considered (50 states and the District of Columbia). Which is one reason that some wineries specialize in only a few states; their wines are not available anywhere else. Some wineries choose to do their own compliance. Professional compliance companies exist to handle details, but this becomes an added expense.

If you were to walk into one of the 100+ locations of Houston-based Spec's Wines, Spirits & Finer Foods, you would be awed by the incredible selection of wines. Carrying such a large inventory in so many locations is expensive. Wines stay on store shelves and in warehouses until sold, which in the case of expensive wines can take time. And time as money.

Economists who look at such businesses where inventories can be economically burdensome often suggest that more prudence in purchasing is essential to staying in business. Some retailers and restaurants now are looking at doing precisely that, recalling the old principle that approximately 80% of a store’s profits come from about 20% of its products.

This 80/20 principle was first introduced in 1906 by Italian sociologist and economist Vilfredo Pareto at the University of Lausanne and later called the Pareto Principle. It stated that roughly “80% of consequences come from 20% of causes.”

About 15 years ago at a wine-marketing conference in Spain, David Francke, who then was managing director of California’s Folio Fine Wine Partners, estimated that 10% of American adults consume about 98% of all the wine sold in this country.

Anecdotally, I hear of restaurants and retail stores throughout the country cutting back on purchasing and relying on existing inventory.

In recent years, both at retail and in restaurants, business managers are asking the not-so-rhetorical question: “Why are we carrying so many chardonnays? Especially when wine sales have collapsed?” And the obvious result is that retailers and restaurants are reducing what they now stock and sticking with the brands and styles that produce more regular sales.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Wine Discovery:

Relic’s 2019 Hyde Vineyard Merlot ($85 per bottle, 149 cases made)

In a region best known for chardonnay and pinot noir, Relic’s 2019 Hyde Vineyard Merlot stands apart. Produced from a six-barrel lot sourced exclusively from the storied Hyde Vineyard in Carneros, the wine shows how site, clone and cellar choices can align to produce a bottling of both precision and depth.

The vineyard’s cool, marine-influenced climate and clay-rich soils offer ideal conditions for merlot. Clone 181, originally from Bordeaux, contributes aromatic lift and vivid color — both clearly present here.

In the glass, the wine is a dark, opaque ruby with a near-black core. Aromatics lean into concentrated dark fruit — damson plum, blackberry and cherry compote — joined by notes of mission fig, baking spice and a trace of bourbon vanilla.

The palate is rich and structured, with black cherry and red currant flavors energized by fresh acidity. Aged 21 months in 50% new French oak, the wine is polished yet fruit-driven. Fine-grained tannins frame a long, savory finish layered with mocha and black olive.

Unfiltered and limited to just 149 cases, the wine is drinking well now but has the structure to age through at least 2029, according to Wine Spectator’s Tim Fish, who awarded it 94 points.

Bottom line: This is a finely made, site-expressive merlot that reinforces both Hyde Vineyard’s range and Relic’s reputation for crafting some of Napa Valley’s most nuanced, vineyard-driven wines. It rewards close attention, offering immediate appeal and aging potential - Tim Carl

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is B: "Elimination of middle agents." "Disintermediation" refers to the removal of intermediaries in a supply chain — such as wholesalers or retailers — allowing producers to sell directly to consumers. The term originated in the financial world in the 1970s, when investors began bypassing brokers, but it has since become highly relevant in the wine industry.

As Dan Berger explains, the U.S. wine market operates under a mandatory three-tier system: producers must sell to licensed wholesalers, who then sell to retailers, who in turn sell to consumers. While this system was designed after Prohibition to regulate alcohol and ensure tax collection, it has become increasingly burdensome for smaller wineries, especially as large wholesalers consolidate and drop smaller brands.

With distributors like Republic National Distributing Co. exiting California, many wineries are left without a sales pipeline. In response, some are pursuing disintermediation by investing in direct-to-consumer sales, tasting room outreach, wine clubs, and e-commerce platforms. While this bypasses the traditional system, it also introduces new logistical challenges — such as navigating 51 different sets of state and federal compliance rules.

In short, disintermediation reflects both a survival strategy and a shift in power — giving wineries more control over how they connect with drinkers, even as the landscape grows more complex.

We hope you enjoyed this week’s challenge and look forward to next week’s word.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

—

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.