Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: Clearly Diminished

Why chasing visual perfection in white wine comes at the cost of aroma and flavor.

We Need Your Help

If you’re reading this, you care about independent, locally owned, ad-free storytelling — reporting that puts our region’s stories first, not corporate interests or clickbait.

Join a community that values in-depth, independent reporting. Become a paid subscriber today — and if you already are, thank you. Help us grow by liking, commenting and sharing our work.

Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: Clearly Diminished

By Dan Berger

That bottle of white or rosé wine you’re having tonight: You hope it will be very good. And with today’s wine technology as good as it is, likely you’ll enjoy it. There will be fruit and some complexity – an evening delight. Any good wine should do that. Even modestly priced bottles still can deliver enjoyment and compatibility.

But that wine could have been better. And probably was some time ago. Chances are strong that almost every white wine that is now in the marketplace was better before it left the winery, at least in one respect. That’s because we are all asked to accept that the white and pink wines we buy have been abridged for absolutely no reason relating to aroma or taste.

What’s at play here is a little game that most domestic wineries have been playing since the 1950s and that is not designed to improve anything particularly meaningful to a glass of fine white wine. In fact, it is a tactic to reduce its overall persona.

It is almost exclusively designed to make customers feel that the wine they buy looks good. That’s it. I don’t know about you, but I do not drink a wine’s color. I drink the wine. And the color is somewhat incidental to that goal.

Actually, there are several different things that wineries do that are aimed solely at making wines look better. And many of them are things that no winemaker, if he or she had their druthers, would undertake.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

This takes a little (or a lot of) explaining. For thousands of years, wine was nothing more than fermented grape juice. Then technology entered the picture. A lot of white (and red) wine was either cloudy, hazy or displayed crystals, had sediment and was relatively unstable. It changed bottle to bottle.

And fine-wine lovers were perfectly satisfied with fine wine’s erratic nature. There’s an old saying that there’s no such thing as a great wine, only great bottles of wine. I used to think that was silly. Then I was exposed to the phrase “bottle variation,” and I began to realize that one of the incredible charms of wine was not its consistency but it’s absolutely insane inconsistency.

But inconsistency has no place when it comes to broad market consumer products that people rely on. Just imagine what would happen if Heinz Ketchup or your Big Mac or your Pike Place changed from day to day. Loyal buyers wouldn’t be so loyal. Sales would take a nosedive.

I do not drink a wine’s color. I drink the wine.

American wine consumers see the parallel to wine. If you believe that quality chardonnays should be as clear as a Northwest stream, you are probably unlikely to accept a bottle of chardonnay that has, say, crystals at the bottom of the bottle. For decades, this was a common problem. Real wine-lovers understood and never got upset. And things changed. Here is the genesis.

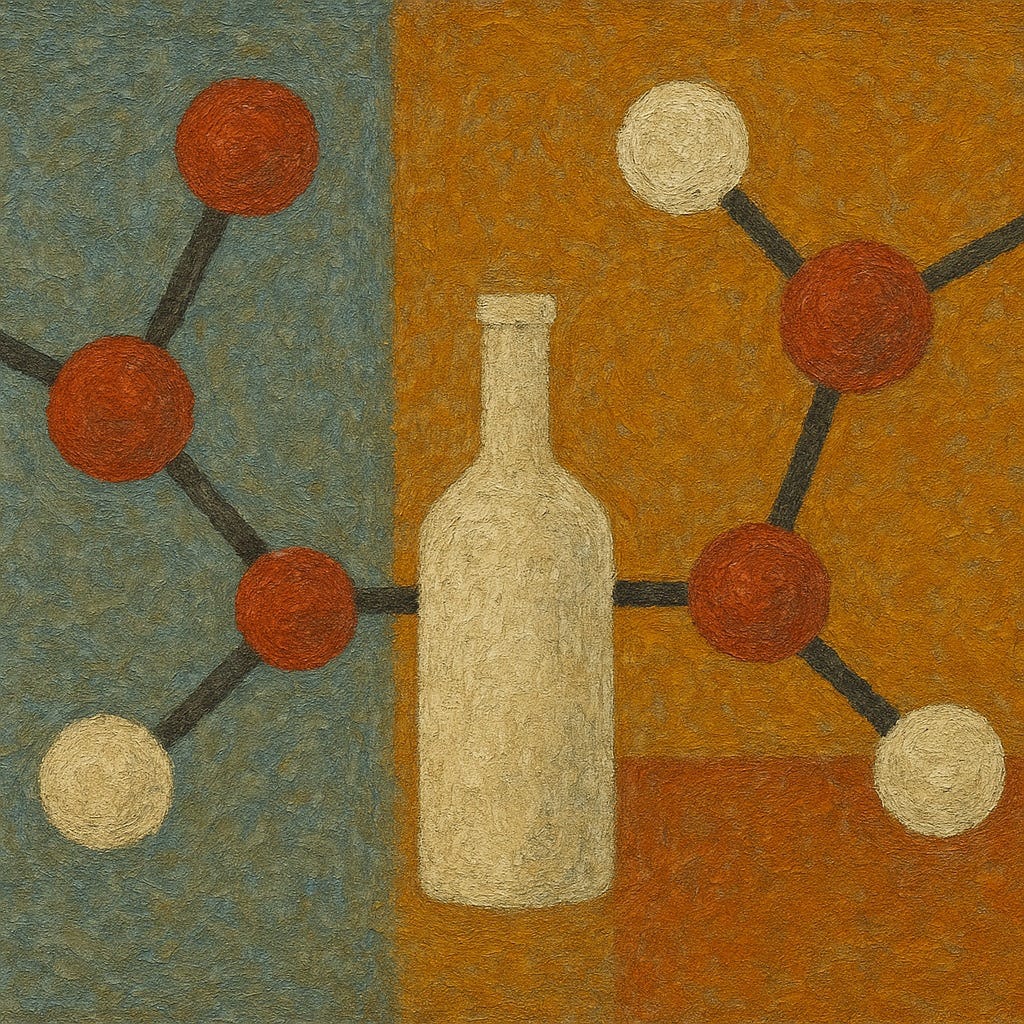

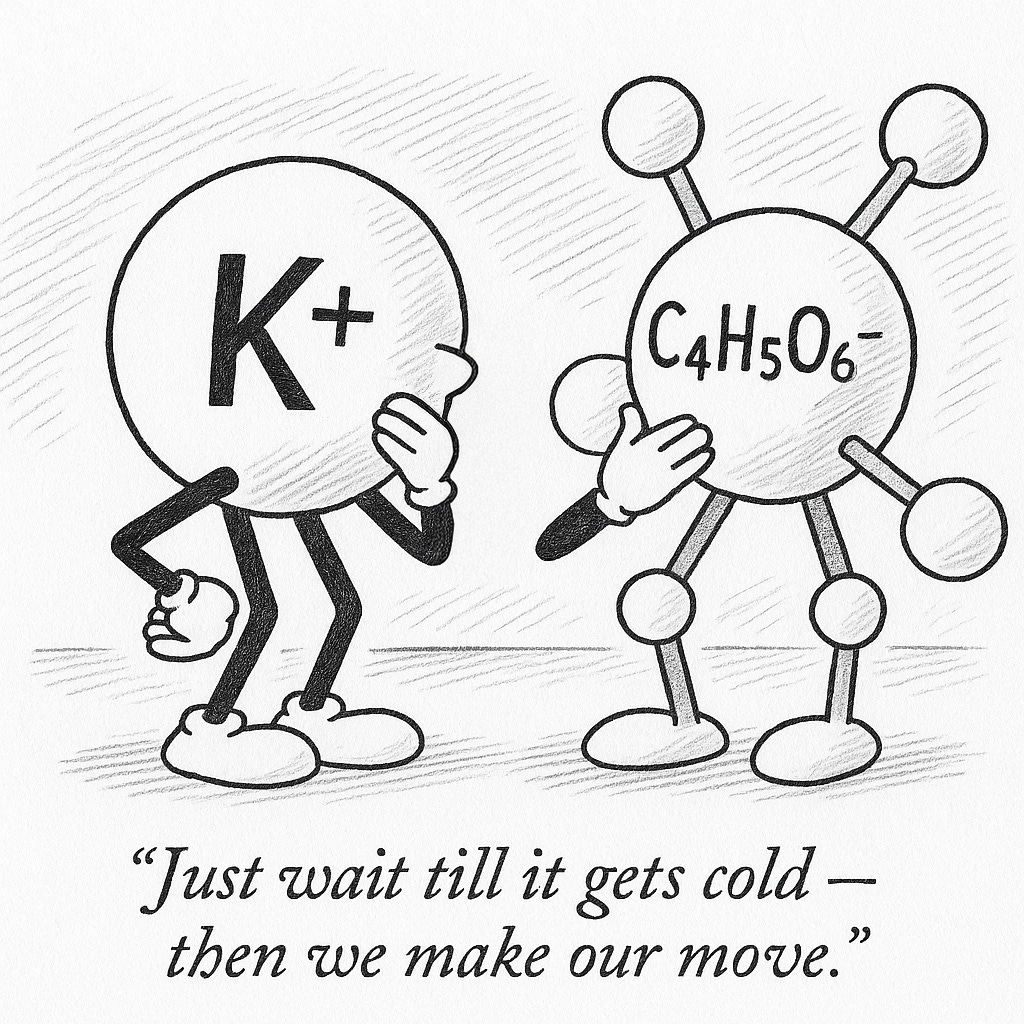

When grapes are fermented, tartrate ions from the tartaric acid in the wine combine with potassium ions to form potassium bitartrate. This element is relatively stable in water but less so in alcohol. And it is really unstable when a wine is chilled.

Depending on the temperature at which it is chilled, potassium bitartrate can drop out of solution and coalesce into crystals. The colder any wine is chilled, the more tartrates are at risk of falling out of solution. The resulting crystals are harmless and virtually tasteless. But, oh, you can see them, and there’s the rub.

In the 1970s and 1980s, before wineries had to deal with this issue — and didn’t — some consumers got upset when they spotted crystals. More than a few people grumbled that their wine bottles had “broken glass” in them. At one point a good friend and winery owner, Peter Friedman, called me to say his wholesaler had moaned that he had received calls from irate customers about his unsightly but otherwise delicious chardonnay.

The problem existed because his winemaker knew that “repairing” this problem before the wine was bottled entailed chilling the wine significantly to remove all possible traces of potential crystals. Peter’s winemaker was reluctant to chill the wine at very low temperatures because he knew that it stripped some of the wine’s flavors and aromas.

Peter solved the problem by printing stickers for the back of each bottle saying, in effect, that the appearance of crystals showed that the wine underwent less processing and was therefore a better wine because of it. Which was an accurate statement.

I have been following this issue for more than 40 years. In 1978, during a tasting I attended, 20 chardonnays had been well chilled in a refrigerator prior to the event. Ten displayed tartrate crystals on their corks. It was my first exposure to this issue. Just a few years later, the “problem” had declined.

In 1983 at a wine-tasting, 129 bottles of chardonnay had been opened by an efficient woman who had placed the corks, wet side up, in front of each bottle. Only 20 of the corks had tartrate crystals, roughly 15% of the group. It was obvious that a lot more wineries were cold-stabilizing their chardonnay. Again, the aroma and taste both were compromised (to a small degree) solely for the purpose of making the wine look better for American wine-buyers

Then in 1990 at another wine competition, 278 chardonnays had been opened. Again, the same woman placed the corks in front of each bottle. I walked down the row, looking for crystals. This time I found only two corks with faint traces of crystals on them, and I had to squint to see them. In both tastings, the wines had been refrigerated overnight to about 40 F.

This meant that more than 99% of the chardonnay I saw in 1990 had undergone cold-stabilization at the winery to eliminate the possibility of tartrate precipitation. Clearly there had been a change from 1980 to 1990 – and a greater change from the 1970s when crystals were far more common.

It’s easy to understand how bothersome this is to someone who cares more about aroma and taste than what a wine looks like.

And the reason I was so upset was that I had a much more graphic expression of this problem in late 1984. St. Clement Winery winemaker Dennis Johns sent me two bottles of his 1983 chardonnay for review. I put one in my garage and the other into a wine rack underneath a staircase, intending to open that bottle for review. I was planning to try the other one in a few weeks.

Early the following morning, I went into the garage and noticed that the “extra” bottle of St. Clement chardonnay had quite a collection of crystals at the bottom. The first bottle did not. I then remembered that the overnight temperature in Santa Rosa had reached 27 F, and checking my min-max thermometer, I saw that the nighttime temperature inside had been 30 F. The second bottle was now cold-stable.

When I tried the two wines side-by-side, the chardonnay from my garage, the one loaded with crystals, was clearly less aromatic than was the wine that I had taken into my home the night before. I called Dennis, who told me that he hated to do any cold-stabilization and that his normal regimen was to chill the chardonnay in a tank down to about 36 F.

Cold-stabilization that goes on in wineries is done at different temperatures. Some wineries choose to reduce the temperature of the wine well below freezing in a tank. A few wineries know how damaging this can be and choose to cold-stabilize at a higher temperature.

(Recently I was told a story I could not verify: Some 40 years ago, a highly regarded Napa Valley winery that specialized in cabernet cold-stabilized its cabernet at about 45 F, which produced a more authentic aroma as well as leaving the acidity without any reduction. But it ran afoul of an industry wine scold, who criticized the wine for being too tart.

Dennis told me he found that if he had cold-stabilized his chardonnay below 36 F, it would really have suffered. And he also said that his sales team at the winery encouraged restaurants to keep their wines at around 50 F.

When winemakers are honest – and I agree not to use the winemaker’s name in print – they usually admit that the lower the cold-stabilization temperature, the more the wine is negatively affected. Higher is better. But a higher temperature runs the risk of tartrate crystals developing in any white wine that later is well-chilled. Doing that frequently results in tartrate crystals. It is one reason that I have heard of high-quality restaurants in Europe (i.e., Michelin-starred) having special wine storage rooms that are not as cold as food refrigerators.

Cold-stabilizing can, of course, be done in some regions of the world without any particular intervention on the part of the winemaker. For centuries in France, Austria and Germany, for example, winter temperatures in wineries have typically been extremely low. Some wine cellars never get above 40 F for months. And if the wines need more cold-stabilization, workers just throw open the doors overnight.

In areas of the world where winemakers routinely cold-stabilize all their white and pink wines, most of them know that simply dropping the temperature in a tank might not work. The procedure requires a nucleation site – a place where crystallization can begin to form. Without it, cold-stabilization might not happen. Decades ago one solution was to add finally ground potassium bitartrate powder to the tank – the same stuff the winery is trying to remove — to get crystallization started.

In recent years, several products have been developed to institute a cold-stabilization process that does not entail chilling. Such additives have become popular with people who make white or rosé wines.

This fixation with appearance seems mainly to be a problem among American consumers. I was speaking with a French winemaker about 30 years ago and asked if the wine he was making for the European market was identical to the same wine that we get here. He said that he had to chill the U.S. version of the wine before bottling.

Another problem that exists with white and rosé wines is what winemakers call protein instability. I have almost never seen this problem in an American-made wine (it’s a haziness) and it never bothers me. One reason I am rarely concerned about a slight protein haze is that in many cases the wine is fine. (Protein haze exists primarily in white and rosé wines. It is slightly more common in sauvignon blanc and gewürztraminer.)

It is related to an increase in the temperature of the pre-bottling liquid, and it can be eradicated at the winery by using a fining technique that employs bentonite, a fine powder made from volcanic ash. But the procedure also reduces aromatics and flavors slightly, winemakers have told me. Most winemakers try to avoid bentonite treatments.

It must be stated here that most winemakers are cognizant of the strategies that lead to better flavors and aromas and more stability in the wines they produce. In almost every case, a treatment that is decided upon isn’t arrived at lightly. But the fact that lawsuits have been filed by not very knowledgeable lawyers over the issue of tartrates in whites and rosés has made cold-stabilization a commonplace practice, even though wines’ aromas and tastes do not benefit.

So you could say that cold-stabilization is really a tactic on which the marketing department relies.

Thirty years ago a winemaker told me that he hated to cold-stabilize, but he said, “Hey, people have been sued over this ‘ground-up glass’ crap, and I don’t need that. It’s commercial suicide not to cold-stabilize. The public is pretty ignorant about this, and there are a lot of greedy lawyers who think they can scare you into an out-of-court settlement – until they find out that this ‘glass’ isn’t glass at all.”

Cold-stabilization is basically harmless. Winemakers will tell you that the average consumer, if given a bottle of a cold-stabilized wine and an identical bottle that had not undergone that treatment, would not be able to tell the wines apart. Those who could identify the differences are knowledgeable wine experts — if such a test were conducted side-by-side using good glassware, an environment unaffected by extraneous smells and both bottles were served at identical temperatures. This could be done in a completely blind test or in a triangular test (two glasses of one and one of the other).

However, since cold-stabilization is almost always done to an entire lot of wine, finding a bottle of that same wine that was not cold-stabilized in order to compare them is probably never going to happen outside of a winery.

The one important exception to cold-stabilization comes from the “natural wine” movement. Since there is no widely accepted definition for what constitutes a natural wine, it’s difficult to know whether a particular natural wine was cold-stabilized. Probably the only way to know is to chill the bottle of a natural wine to about 35 F. But since that will certainly lower the acid level and disrupt the balance of the wine’s flavors, I would not recommend it.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Wine Discovery:

2023 Trefethen Dry Riesling, Oak Knoll ($30) : Dry riesling is the “Claire de Lune” of white wine. It starts out quietly, offering as much eminence as can be achieved unobtrusively in a young wine. Alas, most Americans think that’s all it is. They will drink it young. But Trefethen’s prototypical version, like impressionistic music or a Monet lily pond, calls for introspection and time. Drinking this wine quickly misses its true essence. Lime, grapefruit and delicate tropical notes here are the opposite of ostentation. Although the wine says “dry” in its name, it is not austere but delivers a Granny Smith apple verve in the finish. I adore drinking this wine all by itself. Most people, however, may find it more appealing with creamy cheeses or delicate seafood. Most people also will chill this wine to 40 F. That misdemeanor does a great job of subjugating most of its personality. I prefer it closer to cellar temperature (66 F), at which point it begins to emulate very slightly what it will eventually turn into in a decade: a sublime and prodigiously more complex experience. It is a kind of miracle that Trefethen even planted this variety in the Napa Valley. The family did so, however, because at the time in the 1970s Oak Knoll was cool enough. And it is a tribute to the family’s commitment to history, as well as quality, that it has maintained its production of this rare wine. Far too many Napa Valley properties have removed historic grapes in favor of planting more cabernet. I consider that to be utterly disrespectful to the history and legacy of the valley. This wine represents infinitely more to me than most people who consider themselves to be wine experts will ever understand.

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is C: "Warning colors in animals." “Aposematism” is a biological term referring to the use of bright, conspicuous colors by animals to warn potential predators of their toxicity, foul taste or other defensive traits. First coined in 1890 by English zoologist Edward Bagnall Poulton, the word comes from the Greek roots apo- (away) and sema (sign), meaning "a sign to stay away."

In the context of wine, the metaphorical use of “aposematism” can highlight how winemakers sometimes enhance a wine’s appearance — for example, through cold stabilization to prevent haze or crystal formation — to signal quality and cleanliness to consumers. However, just as a vivid warning color in nature may disguise deeper complexity or danger, an overly polished visual presentation in wine might sometimes come at the expense of authenticity or flavor nuance. This parallel invites reflection on the balance between visual appeal and substance, both in nature and in the glass.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

—

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.