Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicle: The Sample Game

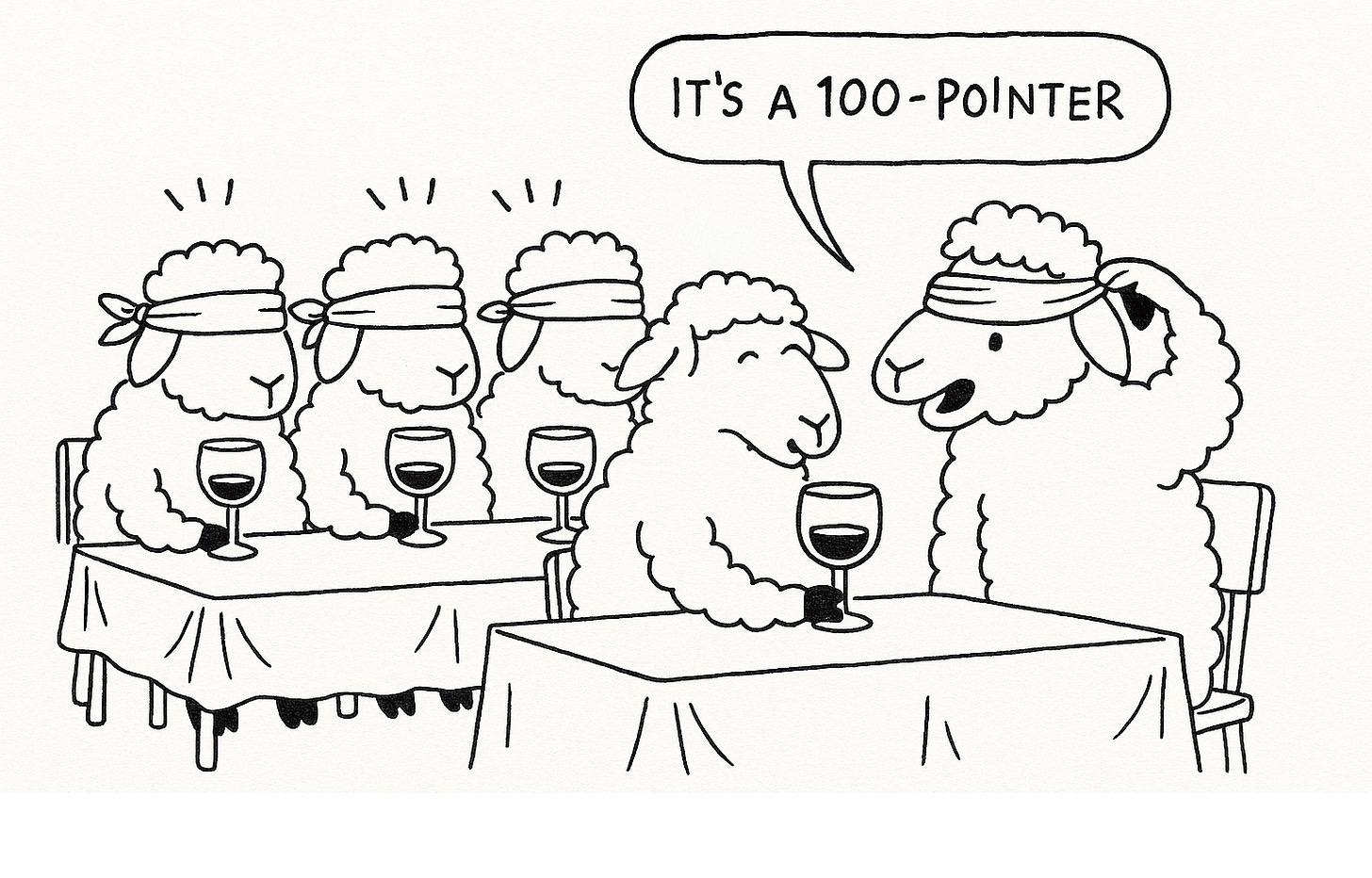

On rumored doctored samples, the myth of the 100-point wine and why what you drink may not be what the critics tasted.

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — It has long been rumored that some wineries disreputably but regularly send special (doctored?) wine samples to certain important wine critics – wines that are specifically assembled to be impressive. According to the gossip, unfortunately these wines do not represent the supposedly identical wines that will eventually appear on retail shops’ shelves, restaurant wine lists or products that are sold directly from the winery to consumers.

The disseminators of these tales say that such wines are “one-offs” specifically designed to impress people who rank wine, especially numerically. The offending wineries hope for a higher score, so wineries that send out “samples for evaluation” are hoping to achieve a high score and thus greater profitability.

Sometimes this is done for certain critics to justify already-existing ludicrously high prices or to bolster a particular brand’s best wine. Or it is done to support what previously has been written about the supposedly exalted brand by other writers.

It is well-known that when one important critic or publication gives an extremely high rating to a particular wine, other publications will try to follow suit. I almost never see one publication give a wine 100 points and another equally glossy magazine give the same wine 77 points. One writer’s 100 prompts others to move their original score (say 93 to 99). There is a kind of follow-the-leader mentality going on here.

I have no idea whether this theory of “doctored sample bottles” has any validity, but it has been in the wind for so long that it has created skepticism about the validity of scores in the view of wine-score cynics.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

One reason I don’t care about this very much is that I have never been interested in others’ points of view about wine quality, especially about the vast majority of iconic California wines (i.e., ultra-reserve cabernet sauvignons). Almost none of these wines holds any appeal for me. As a consequence, I am typically not really welcome in the Napa Valley.

Still, I’m writing a book about cabernet. Honesty and bluntness are my stock in trade. And I don’t mind (and actively prefer) suggesting to winemakers anywhere that they might be misguided, especially when I find that one of their wines misses the point that I believe ignores historical legacy.

I did this recently with a very nice but completely inauthentic semillon from a district well outside of the North Coast. The man who made this wine was pleased that I liked it and was mystified when I suggested that it wasn’t as great as it could be. He took my comments (which were intended to be instructive) in the manner in which they were offered – constructive.

He could see that I was trying to be helpful, and I believe that’s the way he accepted my ideas. He said he had never thought about (or knew anything about) what I was talking about and that he would look into my suggestions. It was a frank exchange of ideas that I hope might lead to a more interesting semillon.

I have also done this occasionally in the Napa Valley about how I believe a winemaker decided to craft his or her cabernet. I do not expect them to change their mode d’expédition, of course, because people’s livelihoods depend on selling the stuff, and the style of wine that I prefer is not necessarily commercially acceptable, especially in places such as Des Moines, Darien or Dubuque.

I know my preferences in cabernet are in the distinct minority. I know, too, that there are numerous wine critics who say exalted things about nearly all of the cabernets produced in Napa. So most of them would probably dispute any allegation that some wineries create special bottlings that are sent to the most powerful critics.

Most wineries know that such a tactic would not work with me. First of all, a while ago, I sent out a memo to wineries asking them not to send unsolicited samples. I told them I wanted only technical sheets that include specific details.

So very few wineries send me samples, but a few who know what I prefer still do. I typically do not solicit review samples. I prefer to do prior homework to reach a point where I’m virtually certain that I will appreciate what the winemaker is dealing with – and that might lead me to finding a product that is acceptable and priced sensibly for my readers.

I may even find something exceptional. It happens.

As a consequence of the preceding, I never gave much thought to special bottlings for certain wine critics. And, frankly, I have no opinion on the matter. I do not use numbers in my ratings as other critics do. My strategy differs from theirs. And I’m sure they don’t care one way or the other about what I say about the wines I love.

As a further consequence, it wasn’t particularly surprising to me when I met recently with a Napa Valley winemaker who was introduced to me by a friend who said that I should hear what she had to say about this rumor of special bottlings designed just for certain critics. It was a subject I did not bring up; my friend did.

This lady has worked at her Napa Valley winery for several years as a winemaker. And she has dozens of friends who also work in Napa and whom she sees regularly. After establishing some parameters, such as my agreeing to keep her name out of any articles that I write about this subject, she agreed to a conversation.

My friend opened the discussion by asking her to talk about special bottles made specifically to go to certain wine critics.

“Sure, most wineries do it,” she said in reply. “It’s very common. Dozens of wineries do it. Usually it’s a high-end wine that they need a high score for.”

She said she had never done it, but the main reason for that is that her winery does not send out samples to anyone. It sells almost all of its products to consumers directly out of its tasting room or to wine club members via the mail. As a result, the winery’s owners do not have the slightest interest in having their wine scored with a numerical rating.

This subject came to mind recently after I read a wine column by the talented British wine writer/analyst Tim Atkin, who said that he had recently read another columnist’s essay that he said “reminded me of a conversation I had in Argentina earlier this year.”

Atkin said, “The person I was chatting with told me that certain producers – he said ‘lots of them,’ but I think he was exaggerating – tailor samples for individual journalists. My disbelief clearly showed.

“‘Don’t be so naïve,’ he smiled. ‘There are Tim Atkin bottles, James Suckling bottles, Patricio Tapia bottles. They choose the style they think you’ll like most.’”

It all sounded awfully familiar to me. In fact, I had a similar experience about 30 years ago in Bordeaux. The episode was funny. I was taken around to various Right Bank châteaux by a local wine wholesaler.

At one exalted château, the winemaker thiefed a sample out of a random barrel, splashed it into my glass and then asked, in French, who I was working for. The gentleman who had brought me to this property translated and said I was with the Los Angeles Times.

The winemaker shuddered. Then he quickly pulled the wine glass from my hand, poured its contents onto the floor of the cave and asked me to follow him to a different barrel. The man who was taking me around the region began to laugh and told the winemaker, in French, that I could be trusted not to write anything disrespectful with any barrel sample because I didn’t make judgments about wines that are still in the barrel. Nor did I use numbers. The winemaker was clearly relieved.

One old rumor says many French houses keep special barrels for certain visiting wine critics. Occasionally, so goes the rumor, the barrels have chalk marks to indicate that a particular barrel is for Critic S or Critic M or Critic P. Cellar workers are admonished never to touch “the M barrel” or “the P barrel.”

The Napa Valley winemaker’s comments about doctored wines at lunch recently were not specific. She declined to name names (naturally), but she said that it was well-known that certain critics liked the smell of new French oak, so particularly oaky barrels would be set aside for those critics. In some extreme cases, she said, specific (legal) additives could be used to “improve” a particular wine.

Atkin weighed in on this in his column last week:

“So much of what I do relies on unspoken trust between me and the producers. Possibly foolishly, I assume that wineries show me what they’ll put on the market.

“Sure, there have been moments when I’ve retasted wines I’d previously given high scores to and thought, ‘Hmm, this isn’t showing as well as it did when I reviewed it,’ but there are always mitigating factors. Was it a good sample? Was hay fever affecting me? What about my mood? Was it the glass, the absence of natural light, the atmospheric pressure?

“Tasting samples from the barrel, it’s a case of buyer – or rather journalist – beware. Years ago, at a château in the Médoc, I asked a cellar hand in French to share the blend for that year’s En Primeur (as-yet unreleased, pre-sale) sample. He started to reel off the percentages like an automaton but then stopped himself.

“‘Sorry, monsieur, that was last week’s blend. No one liked it, so we changed it.’ But bottled wines are different, surely? These are final, final blends. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to expect people to be honest once the wine is finished and ready for sale.”

But what if certain bottles differ from the “regular release” – bottles that the public will never see?

(Then, of course, there are large-production wines that are made in the hundreds of thousands of cases. No winery can bottle, say, 400,000 cases of the exact same wine at one time. Most such large wineries take precautions to make certain that all the different “lots” of wine are identical to the others, but slight or major variations can exist. Which is one reason that it’s extremely difficult to answer questions about the quality of some volume wines that sell for $2 to $3 a bottle.)

The wines I review are tasted either in my office, blind in a wine competition or at walk-around wine events, such as the recent pinot noir festival in Anderson Valley, one of Mendocino County’s premier wine-growing regions. Most of the wines I write about I buy at a local retail store.

I suppose one could make the argument that at wine festivals wineries could bring special wines. But at the pinot noir event that I attended every winery had several bottles of each wine available so they could continue pouring after one bottle had been emptied.

And I witnessed at least a dozen wineries opening second, third or fourth bottles that looked like they had been commercially bottled.

As Atkin said in concluding his article:

“I’m a glass-half-full kind of guy, so I like to think the best of people. I’m not naïve, but nor am I a cynic. After all, what’s the alternative? Lack of trust poisons relationships and leaves the worm of doubt burrowing in your head. So I’ll go on tasting the ‘Tim Atkin samples’ and giving my opinion of them. Fingers crossed, it’s what you end up drinking, too.”

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Wine Discovery:

2022 Markham “The Altruist,” Napa Valley ($30) – Unlike most of her Napa Valley colleagues, Kimberlee Nicholls specializes in merlot rather than cabernet, and one reason for that is that she knows exactly where and how good merlot grows and then how to turn it into a world-class wine. This silky wine could qualify to carry a merlot varietal design designation. By calling it The Altruist, the winery implies the charitable nature it has created using profits that the wine generates. This red blend is exemplary – juicier than a cabernet, and with at least two hours in a decanter it opens up to display some of its 15% blended cabernet herbal notes. Most approachable now, particularly with red meats, the wine is better after 24 hours of aeration. It probably will improve for at least another six or seven years. Bottle Barn in Santa Rosa is carrying this wine for $23.99. — DB

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is B: "Seemingly true but misleading." "Specious" refers to something that has the deceptive allure of truth or authenticity but lacks substance when examined more closely — much like a wine sample made to impress a critic but not representative of what ends up on the shelf.

The word comes from the Latin speciosus, meaning "beautiful" or "plausible," which in turn derives from species, meaning "appearance" or "form." Over time, the word evolved in English to describe appearances that are attractive or convincing at first glance but ultimately false or hollow beneath the surface.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

—

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.