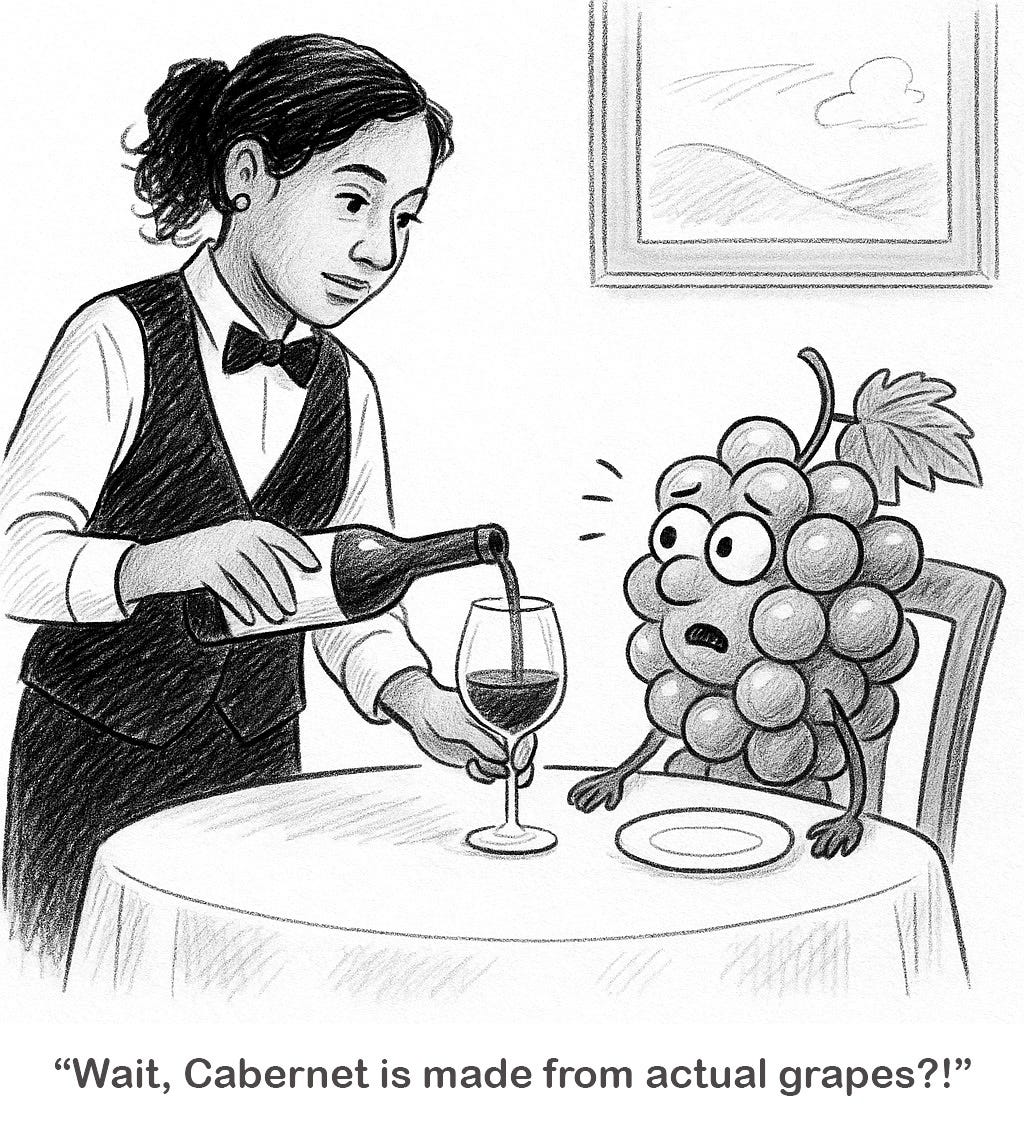

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — A decade or two from now, Napa Valley winemakers will look back on the cabernets of the 1970s and ’80s as “cool-climate” curiosities that bear little, if any, resemblance to the products that began evolving about 2000 into a completely different sort of thing and by mid-century surely will end up tasting more like Port.

The pressures of attempting to make all red wines not specifically for the dining table but mainly to achieve high scores and wines best consumed young began about 1997. What ensued was a strategy to make cabernets that moved away from the classic (balanced), truly dry styles that had been in vogue in California since the 1950s and that were popular with a small coterie of buyers. Most were collectors who aged their cabs.

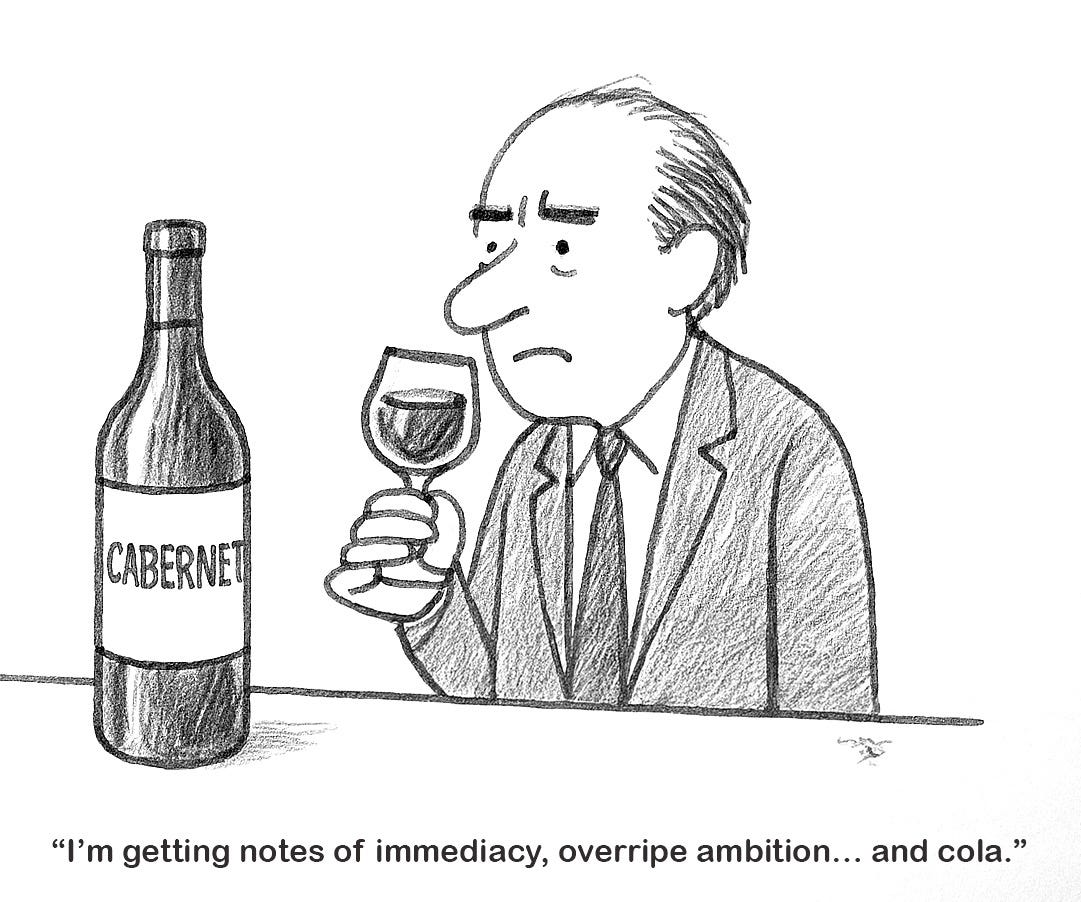

The new strategy includes harvesting grapes extremely late to get more intensity (much of it overripe) because those wines appeal to a tiny group of influential wine critics, most of whom disparaged the earlier, more restrained style of cabernet – even though those earlier wines had proven that they could age gorgeously and were considered to be some of the best cabernets ever made anywhere.

Not so the new stuff. The traditionalists didn’t really appreciate the overt and slightly overdone flavors. They preferred the older style that aged beautifully and had the character of the soil. But they were in the minority.

As the bigger style of cabernet evolved upward and as alcohol levels rose to heights that earlier winemakers would have said were disrespectful to the growers and the grape variety, the other constituents in the wines (such as acid and pH) were compromised, creating an imbalance.

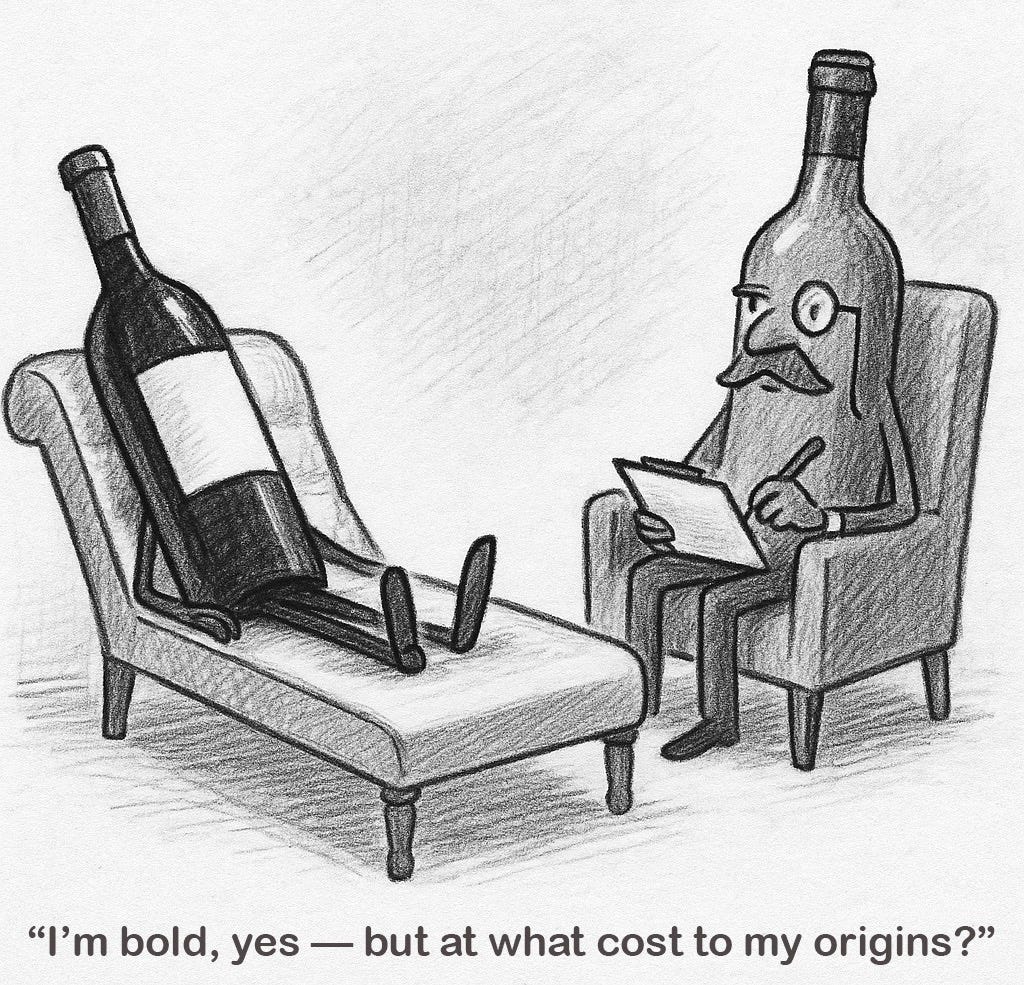

“Great wines taste like they come from somewhere. Lesser wines taste interchangeable; they could come from anywhere. You can’t fake somewhereness.” — Cathiard Vineyard brochure

After a time, the resulting products began to prove that they didn’t age gracefully at all. Most such wines, especially the most expensive, were lucky to be drinkable at age 15. At such a young age, even the best of these wines never showed the complexity that the earlier style developed.

About a decade ago, some observers, including retailers who had been in the business for several years, were beginning to talk about today’s cabernet as a cocktail wine, best served young while walking around, not something you would serve with fine food. They were called, disparagingly, “fruit bombs.”

The real reasons why the style of almost all cabernets changed also had to do with several other factors. One was that many wine-drinkers in the United States haven’t been widely exposed to the traditions of fine red wines, and this has shaped producers’ stylistic choices. In this mode, aging was not required — or advisable.

As the new cabernets became a parody of themselves, the earlier balanced style of wine was roundly criticized by some critics, who were simply not very knowledgeable about California’s cabernet legacy. What the industry was creating, I and others began to see as CINO — cabernet in name only — wines that bore little resemblance to the grape’s classic profile and offered none of its traditional aging potential. Most of the wines had no aroma that reminded traditionalists of the grape variety.

By about 2000, many wine-lovers and collectors began to see the changes in domestic red wines. I began hearing from them. Many said they had decided to look back to France to see if Bordeaux could solve the problems they faced here of excessive alcohol and a lack of character or complexity.

They told me that most California cabernets were simply too sweet, too soft and lacking in any distinctiveness. Some said local cabs had a maddening proclivity to die too young before they ever developed the complexities for which great cabernets and Bordeaux are renowned.

The huge Bordeaux district in France has always produced wines of lower alcohols and better balance, mainly because its continental climate dictates — to a degree — the styles of wine that can be made. And that style is far more conducive to balanced wines, a style of red wine designed to be paired with food and one that will become sublime with long aging in a wine cellar or a properly designed cool space.

Several Bordeaux properties did believe in the anti-historical “richness” concept because a high score will sell a wine faster and for more money. For a time, a few Bordeaux producers made their wines softer and loaded with oak to achieve high scores. It meant making red wines that simply were not very much like Bordeaux. Some of these wines sold well; a few were in such high demand that their prices rose ludicrously.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

However, that tactic only lasted for a brief period of time. Most historically important houses in Bordeaux are so protective of their house style that they rigidly held to their historical roots, and that included dozens of producers who cared more about their wines smelling and tasting like their district than they did about scores. They weren’t willing to compromise their principles to get a high score.

To use an obvious example, three of the finest houses in Bordeaux are Mouton-Rothschild, Latour and Lafite-Rothschild. They are all in Pauillac. Bordeaux purists would say that all of them display a kind of Pauillac-ness, which differs from other districts, such as St.-Julien, Saint-Éstephe or Graves.

This is one of the key differences in comparing California cabernets to one another and a similar tactic in France. In Bordeaux there is a historic emphasis on regional identity going back 200 years or more. By contrast, most California cabs are mainly crafted to get high scores, and that almost never includes even lip service to regional character.

Some Napa producers love to argue that their sub-districts do have unique characteristics based on their soils. However, their case falls apart when you try the wines blind. For the most part, Napa cabernet has been homogenized into a similar — if not identical — format in which varietal distinction and regional identity carry zero weight. It all must be dark, concentrated, with higher alcohol and lower tartness.

The old style is still with us, thankfully, although the producers are scant in number.

The outliers, bless them, have made exceptional wines that lean back in the direction that was popular 50 years ago and still appeals to people who understand why cabernet was made in that style in the first place. I am often asked which properties pay homage to history, and I’m always reluctant to create a list because I might miss a few producers who deserve to be on it.

Still, I owe it to a few heroic producers whose cabernets continue to display an understanding of structure and balance. These traits have always been a prominent feature of their wines. These houses include Corison, Chateau Montelena, Ridge, Smith-Madrone, Frog’s Leap, Spottswoode, Opus One, Mayacamas, Matthiasson, Clos du Val and a few others. I welcome suggestions. (winenut@gmail.com)

From the above brief list of wineries, it is clear that understanding structure and terroir doesn’t require having been born in Bordeaux. All of the California wineries mentioned here have winemakers who worked almost exclusively in California and are respectful of California’s cabernet history. And they understand the connection to Bordeaux.

Two decades ago, while researching a story for Decanter magazine in London, I interviewed seven transplanted French winemakers who then were making wine in California. I asked them about the skills they brought with them that allowed them to succeed with California’s warmer climates and still make classically styled “euro-visionary” wines.

The interviews were remarkably enlightening because each interviewee had a singular message that differed from the other responses. The remarks gave me insights into how best to make a California wine that was respectful of its soil and climate (in a particular year) and to aim for better balance than most California-trained winemakers were doing.

The result of their training was that the cabernets they produced were designed to be aged properly, and if consumed young, they were so beautifully structured that the wines were still enjoyable.

Each of them provided slightly different strategies about what they learned in viticulture and enology schools in France before moving here. The most important details I could glean were their requirement of walking the vineyards leading up to the harvest and then tasting wine, seeking subtle aspects that included what they were picking up from tasting grapes just before harvest in their vineyards.

In none of the interviews was there a single mention of alcohol, oak or intensity. One word that seemed to be universally used was “balance.” I also picked up what I believe was another message: The best wines they were making were not wines of intensity but of personality. And that included most importantly what their vineyard sites provided.

Soon after those interviews, I acquired one or more bottles of the wines from each of the seven French expatriate winemakers and served them blind to several industry friends with some California versions from the above group. Most of the French-winemaker wines were identified as being not from California but from a producer who understood balance and structure. Which implied that many California wines today reflect a preference for immediate approachability, which contrasts with the European emphasis on ageworthiness and food pairing.

It was this extremely subtle element that struck me when I first smelled a red wine from Cathiard Vineyard, a relatively new project. I heard about it roughly five years ago after its acquisition by a French wine family about whom I knew little.

That first taste was a revelation. There was a distinctive Bordeaux sensibility that also included traces of the dried herbs that marked early cabernets from Rutherford, where the estate is located. That initial aroma of the Cathiard wine did not surprise me because the owners of this estate are also the same people who own an esteemed property in Bordeaux, Château Smith Haut Lafitte. This fact becomes important, as we will soon see.

Napa Valley residents might remember that the property the Cathiards now own is the former Flora Springs Vineyard and Winery that sits at the base of the Mayacamas Mountains in the western foothills, a property that the Komes family farmed for five decades, from 1978 until it was sold in 2020.

Daniel and Florence Cathiard’s acquisition of the property was not ostentatious because they knew that several years of work would be required to retrofit vineyards, redesign the interior of the winery, and do additional structural and cosmetic changes to allow for French sensibility to permit a structured and balanced wine to be produced.

And the best way to achieve that was to bring in a general manager and winemaker who understood precisely what making a structured wine from grape varieties like cabernet is really all about. What it is not about is softness and early drinkability.

French-trained Justine Labbé was the choice as winemaker. She and a talented team changed numerous aspects of the winery and vineyards, switching the farming to all organic, converting some merlot vineyards to cabernet, adding special conical fermentation tanks and — above all —bringing in a vision of French character to the California fruit.

This is evident when you smell the wines and taste them, which I believe validates the new project’s primary goal of making structured wines. Cathiard’s wines could be illustrated by an important message that is found in a small brochure that the winery offers:

“Great wines taste like they come from somewhere. Lesser wines taste interchangeable; they could come from anywhere. You can’t fake somewhereness. You can’t manufacture it … but when you taste a wine that has it, you know.”

As proprietors of Smith Haut Laffite, the Cathiards know about this issue that the French call “terroir,” a kind of taste of the place, which is most important for estate wines like those from their own Bordeaux property.

Smith Haut Lafitte is located in Pessac-Léognan, south of the city of Bordeaux. Just over a mile and a half from Smith Haut Laffite lies the gravelly-sandy wine district of Graves, whose wines usually are distinctively rigid, with a sort of gravelly-ness that is part of the charm of local wines.

The Cathiards’ Napa property includes one of the most revered vineyard sites in Napa. It is at the very end of Zinfandel Lane, in the literal shadow of the sloping east-facing Mayacamas range. There are 58 acres planted (on more than 150 acres of land).

One reason this property is special is that it sits facing due east on a sloping hillside. As with many vineyards in this region, the sun begins to sit on the vines sooner each day than it does on the vines planted on the valley floor or on the western facing slopes on the other side of the Napa River. This means that grapes get less overall sun, which means that they are farmed slightly differently and produce a little bit more of the essential herbal components that classic cabernets display.

Another feature of the property, which ultimately will enhance the overall subtlety that seems to be embedded in the wines, is complete control over the aging of the wines in oak barrels. During her multiyear renovation of the property, Labbé created a space where barrels can be assembled from French-grown staves.

This is a critical factor in getting barrels to do exactly what she wants them to do. As such, she works closely with her compatriot from France, Alban Trouvé, the only winery cooper making barrels in the Napa Valley. The barrels are unique to the estate.

As for the vineyards, several of the techniques that came from France include changing the trellising system slightly to improve airflow, which Labbé says provides more control over the ripening cycle. Also, she is cognizant of the increase in direct sunlight as well as higher temperatures and is doing vineyard work to maximize quality.

“We are looking for a little bit more elegance in the wines,” she said, and that is evident in their balance.

That is exactly what I found in the three wines that the company is now making, headed by the winery’s top-of-the-line Cathiard Estate ($395), a wine that displays all of the character of Rutherford. It is loaded with black cherry and herb components that improve with aeration. It is superb.

A wine called Founding Brothers (2022, $225) displays a beautiful structure along with excellent minerality, and a third, introductory style wine is called Hora. (see below)

The Cathiard project will probably not change what others in the valley are doing, but the French sensibility that the Cathiards have brought there authenticate the older style of cabernet. If the pendulum is, in fact, swinging back, this is a positive step in that direction and a validation that Napa can still produce more classically styled wines.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Wine Discovery:

2022 Cathiard Hora, Napa Valley ($125) – There is an elegance here that you rarely find in most Napa Valley cabernets that are this young. Part of the reason is that the blend includes substantial cabernet, merlot (for softening) and malbec (for brightness of fruit). There is a beautiful depth of flavor. And what I really appreciate is that it has noticeably better acidity than many of the more iconic (and more expensive) red wines being produced in the Napa Valley. — Dan Berger

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is B: “Peak maturity of a wine.”

“Apogée” refers to the moment when a wine reaches its fullest expression — the ideal balance of aroma, texture and structure. For wine lovers and producers alike, knowing when a wine is at apogée can make the difference between a transcendent experience and a missed opportunity. In Napa, where the debate over aging potential and stylistic direction is ever-present, the idea of apogée resonates with those who value patience, restraint and complexity over immediacy and impact.

The term comes from the Greek apogeion — apo (“away”) and gaia (“Earth”) — and originally described the point in the moon’s orbit farthest from Earth. French winemakers later adopted “apogée” metaphorically to describe a wine’s highest point of maturity. Its entry into wine discourse reflects a broader sensibility: that great wine, like a great idea, arrives at its moment through time, care and place.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.

Having followed the evolution of the California wine industry since 1972, I’ve seen many changes in winemaking styles aimed at appealing to new markets and critics whose rankings drive sales. You’ve nailed the trend over the past two decades, where winemakers have prioritized scores over style. Their big extract, thick, tannic, high-alcohol fruit bombs taste a lot alike and lack any sense of place.

In contrast, it is possible to find fine California wines with style and a sense of place. The late Maynard Amerine, the legendary scholar from UC Davis, wrote over 40 years ago that the best Napa Valley wines exhibited a similar style in both the nose and on the palate. Some of the characteristics of the “Napa nose” are the classic herbaceousness of Cabernet fruit, cassis, berries, mint, light oak, and hints of spice. As you noted, Bordeaux experts can distinguish wines from Pauillac, versus those from St. Estephe, St. Julien, Margaux, and Pessac-Léognan.

The classic wines from Napa in the 1970s and 1980s (BV Private Reserve, Caymus, Robert Mondavi Reserve, Mayacamas, Phelps, Spring Mountain, Heitz, etc.) had style and alcohols in the 12.5 to 13.5 range mostly. I’ve continued to taste older California wines over the years and been pleased. The wines with lower alcohol content do evolve nicely. As with fine Bordeaux and Burgundy wines, they can age with grace and be paired with a wide range of cuisine, complementing but not overpowering other flavors. Today’s monsters don’t go well with much except ripe cheeses, ribs, and barbecue.