Wine Chronicles: A Case for the Overlooked Wines of the World

By Dan Berger

Article Thumbnail: Today Berger explores how obscure and underappreciated grape varieties offer unique, high-quality experiences that are often overlooked in favor of mainstream formulaic cabernets. He traces the history and geography of rare grapes in the United States, noting how climate, press bias and consumer habits have shaped their presence. Through personal anecdotes and examples he highlights a growing interest in these lesser-known wines and their potential to broaden the wine-drinking experience.

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Federal statistics, which often are unreliable, recently showed that about 60% of the Napa Valley is planted to cabernet sauvignon grapes and that about another 30% is planted to well-known varieties such as merlot, sauvignon blanc, chardonnay, pinot noir (the latter two mainly in Carneros) and zinfandel. And there are smaller amounts of chenin blanc, petite sirah, syrah, riesling and cabernet franc.

Which means that trousseau noir, counoise, refosco, ribolla gialla, schioppettino, lagrein, sangiovese and pinot meunier, combined, represent just a tiny percentage of Napa plantings. And the number of Napa wineries that produce these wines probably could be counted on one hand. Among them are Forlorn Hope, Matthiasson and Lola.

The sad thing is that some winery owners have abandoned historical connections to relatively obscure varieties that once did brilliantly on their properties. Among other grapes that today are about as popular as a mariachi lullaby are charbono, grignolino and semillon. (Heitz Cellar once made a fine red wine from its historic grignolino vines as well as a spectacular dry rosé from the same variety. Alas, that wine seems to have been abandoned.)

Wines from many of the above grapes and dozens of others are so obscure that they have no chance to become popular with those people who buy $300 cabernets. But there is a soundless groundswell for the abstruse, and it is not insignificant. It seems to be growing even without any attention being paid to this category by major wine critics who claim to know a lot about wine.

However, most of the wine press really know mostly about the popular stuff. Most of them know nothing about the fascinating aromas and flavors to be found in blaufrankish, cortese, saperavi, St. Laurent, Frontenac, Brianna, vignoles and Zweigelt. And dozens of other rare-grape wines are now being imported to the United States from places most wine-lovers don’t even know are places.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery wine word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

I recall that in the 1970s, Bolla Soave was extremely popular throughout the United States. But at the time a wine-shop clerk told me he wasn’t sure which was the grape variety, Bolla or Soave. (Bolla was the brand, Soave was the wine and the grape was garganega.)

In my experience, most of these rare-grape wines now are being purchased by wine-lovers who are, they tell me frankly, getting awfully tired of the same old same old. As am I. It seems like most cabernet producers are making cab exactly the same way, formulaically: Every bottle has an alcohol level I cannot abide, acids that are so soft that the wines are flabby and flavors that are manipulated beyond what Mother Nature would recognize as her offspring.

Rare-grape entries can be fascinating – and some of them even have a bible, of sorts.

Seven years ago author Jason Wilson published “Godforsaken Grapes,” which he deftly subtitled, “A slightly tipsy journey through the world of strange, obscure, and underappreciated wine.” At only 320 pages, this charming book details Wilson’s many travels around the globe to try some of the finest obscure grapes that have been turned into consumables.

As short as it is, the book cannot really do justice to some of the grapes that are mentioned above. But Wilson does a commendable job, and his writing is engaging. More intellectually, most of this territory was previously explored in depth by the estimable Jancis Robinson in several brilliant works, including her magnum opus, “Wine Grapes.”

“Godforsaken Grapes” is a superb and charmingly written Baedeker/homage to vinous incomprehensibility and a primer for anyone who wishes to begin exploring exciting wines that get virtually no acclaim from those who believe that the best wines in this world deserve 100 points and anything less is somehow flawed.

In a non-political context, this is tantamount to varietal prejudice. Got a red wine that’s light in color? Give it 82 points and disparage it.

In effect, it is like saying to wine consumers, “This saperavi has a terrific aroma, a perfect structure, it tastes great and probably will be better in a few years, but it deserves only 89 points because, uh, well, it’s only saperavi, after all, and it’s from New York, and I really don’t know anything about it. So although I love the aroma and I love the taste and I love the structure and it went great with my dinner, it’s still not worth more than 87 points.”

It’s just prejudice against the unknown. I wish someone would finally admit, “I just don’t have the time or the patience to research this thing called charbono, so I’ll just give it a mediocre score. I have more important things to do.”

Prejudice against rare grapes and the wines they make is relatively commonplace throughout this country. There are wineries in every U.S. state. Many are where chardonnay and cabernet simply cannot grow because of climate or soil conditions that limit production and make it impractical to grow the French varieties.

This was true for decades in upstate New York’s Finger Lakes, where an extremely limited number of French varieties could grow. Dr. Konstantin Frank on Lake Keuka pioneered using French grapes in his experimental vineyard starting in 1957. I visited his winery at Hammondsport in 1977 and was amazed by the quality of his chardonnay and riesling.

But at that time, 50 years ago, almost every other winery in New York state was growing French-American hybrid grapes such as baco noir, seyval, vidal and Cayuga. And a lot of New York’s native American grape, Concord, was being turned into grape juice and grape jelly.

Minnesota is so cold in winter that vines die, so many Minnesota wineries today use hybrid grapes developed by vineyardist Elmer Swenson that withstand cold temperatures. Similarly, many Texas vineyards decades ago planted grapes hybridized by T.V. Munson. Texas has largely switched to French varieties today, but the Munson varieties continue to be produced by several Midwest wineries, including TerraVox in Kansas City.

As grape-growing techniques improved over the last few decades and as climate change allowed for different tactics, French varieties began being planted in places where they could thrive. Washington and Oregon have always had French varieties, but fine French grape wines now can be found in Idaho, Colorado, New Mexico, Michigan, Ohio, Virginia, Arizona and even pockets of New England.

And not to put too fine a point on it, about a month ago, a friend who works as a consultant poured for me a 2020 cabernet blend that was exemplary. It was made by his client, Hawk Haven Winery in Cape May, New Jersey. It sells for $34 and is one of the finest examples of a Bordeaux blend I have had in years.

Today rare-grape wines are slowly becoming mainstream. Some of these wines are made from grape varieties that once were unknown here but are becoming more widely recognized. Twenty years ago, grüner veltliner was the No. 1 white wine grape being imported from Austria, but it was relatively obscure here and very little was planted.

Today two dozen or more U.S. wineries make one. Two of the finest grüner veltliiners in the country are from Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley at Galen Glen Winery and Umpqua Valley, Oregon, at Reustle Prayer Rock.

Similarly, vermentino from Italy and albariño from Spain both have escaped their earlier classification as obscure because imports have proven to be popular. Today both are much easier to find, including many U.S.- grown versions.

What constitutes an obscure grape differs from area to area. In wine-savvy cities such as Los Angeles, San Diego, the San Francisco Bay Area, Portland, Seattle, New York City, Chicago, Miami, Washington, D.C., and even Las Vegas there probably are hundreds or thousands of people who have tasted wines from 100 or more different grape varieties, which would qualify them to be members of the Wine Century Club.

The website for this informal “society” says, “If you’ve tasted at least 100 different grape varieties, you’re qualified to become a member. If you haven’t tried 100 different grape varieties but are interested in the concept, you’re welcome to all of our events. Please join us in promoting the awareness of uncommon wine grape varieties. We currently have 1,961 members worldwide.” The site shows that there are 1,420 U.S. members. There is no membership fee.

As a dedicated lover of many obscure wines, I can attest to the fact that these wines often provide remarkable experiences that surprise me with exotic characteristics that I find to be remarkable because I thought I knew something about wine. But I’m learning all the time.

I keep my hand in this game by getting together with several wine industry people every week for a lunch at which we all bring something murky. In many cases, the wines are blends. Last week’s surprise white wine was from the Douro in Portugal, a blend of four grapes, none of which I had ever heard of. The wine was delightful, and it was not particularly expensive.

If anyone is looking for a grape to plant that might do extremely well in Northern California, I would definitely recommend areni noir. It is a grape I discovered a few weeks ago. The wine (called Khachen) was made in Armenia. A “regular” bottling is $30; a reserve is $55. I am unaware of any areni growing anywhere in the United States.

Areni is an ancient grape that makes full-bodied red wines in Armenia and Turkey, the area of the world considered to be the birthplace of viticulture. The wine we tried was remarkably dark in color, but the alcohol was 13%. The extraction was extremely high, but the wine did not have the usual tannins associated with dark-red wines.

The aroma was a little like a cool-climate syrah with black raspberry/loganberry aromas and a trace of violets. Wilson, in his book, says the areni grape is named after “an Armenian cave complex where archaeologists found evidence of the earliest known winemaking dating to more than 6,000 years ago.” Since my first exposure to areni, I have tried two more blended wines that included areni and found them both to be exceptional.

I’m not a viticulturalist, but I suspect that areni may have a future in California and perhaps other regions of the country.

Another grape that I believe has a future in California but in slightly cooler climates (i.e., high altitude and/or Carneros) is blaufrankisch. A Petaluma Gap winery, 37 Wines, grows this variety and makes a spectacular red wine from it. Confusingly, however, the same grape is called lemberger in Germany, kékfrancos in Hungary and franconia in Italy.

Wilson has an entire chapter on this variety in his book, and he includes in the same chapter the related Austrian variety Zweigelt, a high-acid grape that probably will not do particularly well with American wine consumers. But I have really appreciated those I’ve tasted.

The success of Austrian grüner veltliner wines here in the last decade has encouraged several of the major producers to begin sending a few Austrian reds to this country, partially because most of them are lower in alcohol and deliver unique flavors. I’ve tasted a few of these red wines and find them interesting and tasty, but the grapes really call for cooler climates than Napa has to offer, except perhaps in the Carneros district.

There are several benefits to buying obscure-grape wines. For one thing, people who make them don’t worry about alcohols being too low. In many cases, alcohols are in much better balance than they are in more expensive wines. Also, prices for obscure red wines tend to be lower than iconic reds. And because the rare-grape wines don’t sell as quickly, consumers are likely to find slightly older vintages, which usually benefits buyers because the wine will have additional maturity.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Wine Discovery:

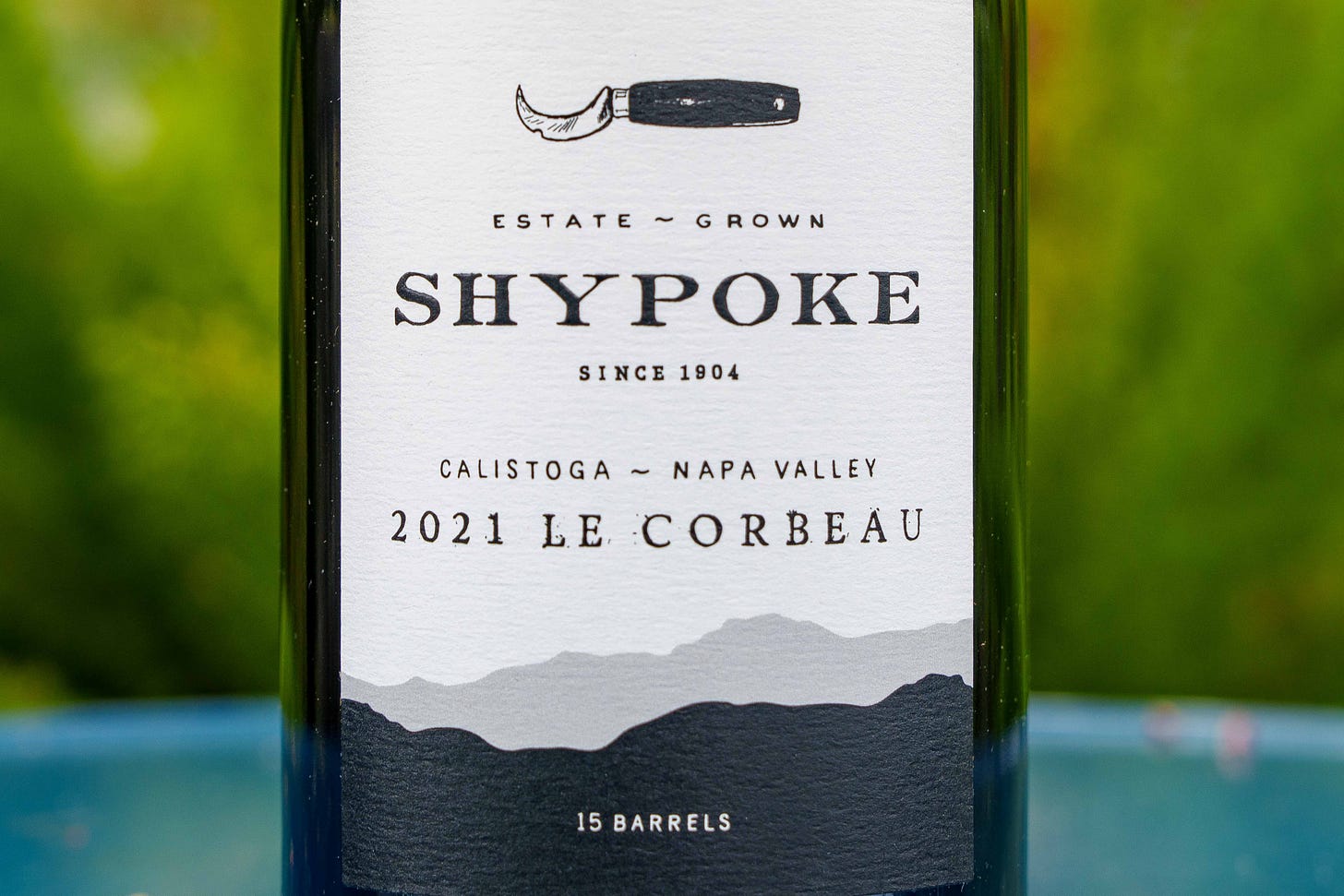

2021 Shypoke Charbono ‘Le Corbeau’ ($45, 15 barrels made) — Sourced from a Calistoga vineyard held by the Heitz (not the St. Helena Heitz) family since the late 1800s, this rare Charbono (or Le Corbeau, as they call it) is crafted by Peter and Meg Heitz using old-school methods that echo five generations of winemaking. Aromatics of cigar box, clove and dried fennel give way to blackberry and cherry fruit, underlined by a subtle streak of vanilla. The palate is focused and textural, with moderate acidity and restrained alcohol lending balance. Pair with mushroom risotto, herbed rack of lamb or Gorgonzola-glazed brisket - Tim Carl.

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is B: “Pressed skins, seeds and stems.”

“Marc” refers to the solid remains left after grapes have been pressed during winemaking — including skins, seeds and sometimes stems. It’s a byproduct with many uses: compost, animal feed, grapeseed oil or even distillation into spirits such as pomace brandy (called marc in France, grappa in Italy). In traditional winemaking, marc can also be returned to fermenting must to extract more tannin or color, especially for robust reds.

The word comes from Old French marc meaning “waste” or “residue,” first documented in winemaking contexts in the 15th century. Though it refers to what’s left behind, marc has long been valued for its utility — especially in peasant winemaking cultures where nothing from the harvest went to waste.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.

Every once in awhile I do a tasting of 'hidden gems' at my wine shop. Recently I included Insolia, Scheurebe, Xinomavro and Malagouzia. The wines always go over well at the tasting, but when the leftover wines go on the shelves nobody buys them.

I love Shypoke Charbono!

There are plenty of wineries producing obscure varieties. At Benessere, we are the only Napa Valley growers of Sagrantino, Teroldego, Nero D'Avola, and Falanghina (so far as we know). And to date we are the only producer of Napa Valley Aglianico. We also have Vermentino. Come explore!