The ocean lay black beneath a sky streaked with smoke. No moon. Just a few stars pushing through the haze, their light dimmed by burning oil platforms on the horizon. On the ship’s bridge, radar screens glowed red. The consoles swept green — slow, steady, watching.

Nobody spoke.

Just the soft click of instruments. The low thrum of systems beneath our feet. Waiting.

The sea looked calm, but the ship shifted in slow, uneven motions — a sway more felt than seen. Below deck the engines pulsed, low and steady. Like an animal waiting to break loose.

We were deep in a declared conflict zone. Two of our ships had already been hit. One had nearly gone down. Lives lost. Bodies unrecovered.

It was 1988. Operation Praying Mantis marked the largest U.S. naval engagement since World War II. The Russians shadowed us from the south. The Iranians launched missiles and scattered mines.

Rumors floated through the mess deck that we’d taken on nukes in Diego Garcia. Nobody said it out loud. Just whispers — scuttlebutt without a face. Heavy. Unshakable. The air felt different after that. Tighter. Harder to draw. As if something unseen had slipped aboard and begun to feed off the oxygen.

I was the Master Helmsman aboard a nuclear cruiser. I’d been on the bridge for hours. None of us had slept more than a few hours a day for weeks. I was one of three sailors trained to steer during combat — through minefields, under fire, during live launches. Every fraction of a turn mattered. Nudge the helm too far and we weren’t just off course. We were dead.

“Helm, stand by. Maneuver incoming. Fire control tracking.”

The familiar jolt in my chest — fast, tight, like my heart was trying to tear its way out.

The next order came.

“Two degrees right rudder.”

“Two degrees right rudder, sir,” I said, hands locked on the wheel.

I eased the helm to starboard. Smooth. Deliberate. No room for error.

The ship responded like a living thing, slow and massive, shifting against the sea.

Then — silence.

I held the helm steady as we slowed to a stop. The ship’s engines hummed low, the bridge wrapped in shadow. For what felt like hours, we sat motionless. Only the faint crackle of the radio broke the stillness.

Then, from somewhere deeper — something appeared.

Not fear. Not doubt.

A smell.

Faint at first. Not diesel. Not the brine of sweat or the smoke of burning oil.

Yeast.

Citrus.

Orange blossom.

Easter. Charter Oak Avenue. 1972.

I was just a kid then, running wild with the Particelli brothers and a handful of neighborhood kids. We spent whole days roaming St. Helena — balancing on train tracks, building forts by the creek, swapping stories about the usual terrors: quicksand, rattlesnake strikes, black widow bites. Or the worst of them all — our mothers calling us home by our full names.

By dusk, we’d drift east toward the big white barn at the end of the street. Something about that place felt older than the rest of town.

The Napa Valley Olive Oil ‘Factory’

Tucked at the far end of Charter Oak, the building looked ancient — broad and whitewashed, surrounded by olive trees knotted with time and citrus trees heavy with fruit. In spring, bees filled the air with sound. The smell of orange blossoms rode the breeze like a promise.

We’d push through the old screen door, its hinges groaning like it had a voice of its own, and step into the dim light. Cement floors worn smooth by generations. Old tracks cut into the concrete to catch runoff from pressing seasons long past, still faintly scented with fruit and iron. The walls were layered with yellowing business cards. A stone press squatted near the back beneath a curling poster of Rome. The air was dense — salt, vinegar, meat. Strings of dry salami swung from rafters like garlands. Prosciutto hung above the counter. Cheese glistened under wax paper.

Mrs. Lucchesi Particelli stood behind the counter — compact, sturdy, always smiling with her eyes. Her family had been pressing oil here for decades. Nothing much had changed — not the tools, not the prices, not the sense that the room itself was holding its breath between stories.

She’d slice thick rounds of salami and hand them out like communion. The first time, I refused — too strange, too grown-up. The others laughed at me and tore into theirs. Eventually I gave in. One bite — sweet, chewy, salty. I never looked back.

But that day she handed out something else.

Golden bread, braided and brushed with egg, topped with colored sugar and flecks of citrus peel.

“Pane di Pasqua,” she said, smiling. “It’s for Easter.”

We stood in a circle, chewing slowly, eyes wide. That bread was different. Not just sweet — it carried history. A whisper of something deeper. A world older than the one I’d come from.

That’s what surfaced as I stood at the helm, hands slick with sweat. Not the missiles. Not the rumors. Not the trawlers lurking just off radar.

Bread.

Home.

Traditions.

And then I thought of Lynn.

She was my girlfriend then. Now my wife. Her family grew grapes in Rutherford — another old name, another thread in the valley’s long story. She sent letters that smelled faintly of fennel, tucked inside coffee cans packed with pieces of home. Cookies wrapped in parchment paper. Baked things full of chocolate and nuts, topped with citrus zest. They arrived warm from the sun, dented from the helicopter-mail drop, sweet with memory.

One bite and I was back. Not just home — but among the citrus trees, in the hush before dinner, friends running barefoot down dusty driveways. Light slanting low. The air warm and slow.

I held my breath as the ship moved into firing position.

“Steady,” the captain said, his voice flat. He turned toward me, held my eyes for a moment, then looked away.

Below, the launcher groaned into motion. A low grind of hydraulics echoed through the bridge — one slow clunk after another. I felt it through the soles of my boots. Each jolt moved up through my legs and into my chest.

No one spoke.

Outside, the water barely stirred. Even the ocean seemed to wait.

I kept the helm centered.

A bead of sweat slid into my eye, and I blinked hard. The radar screen pulsed red and green in the darkness.

The tension sat heavy — not sharp, not loud. Just a low, pressing weight, like a storm crouched just offshore.

Later, after, time folded in on itself.

I sat with my back against my locker, the tin in my hands, unsure if the sun had risen or if night still held. A soft dent ran down one side. The lid was warped from the journey. I peeled it back slowly. Inside — five cookies. A little crushed. One cracked clean through.

The scent rose up — orange, butter, a hint of honey.

Her note was tucked beside them. The handwriting was steady, the loops and lines as familiar as breath.

“Happy Easter. The citrus trees are blooming. I miss you.”

I read it once. Then again. The ink had bled slightly, the way it always did on the paper she used.

Somewhere on the ship, something heavy shifted into place. The vibration moved through steel, through floor, through bone.

I stayed where I was.

There were still hours before my next watch duty on the bridge.

I thought of the other sailors — of everyone pulled into this conflict. The ones who wouldn’t make it home. The ones whose names I’d never know. I thought of those whose decisions had sent us here.

I picked up the cookie that had cracked clean through and held it to my nose.

Butter. Caramelized sugar. Orange flowers. A trace of fennel?

Water lapped against the hull — even and slow, like oars in water, like the steady tick of some distant clock.

I closed my eyes and slowed my breath.

In through my nose. Down into my chest. Hold. Release.

Even with my eyes closed, the memory of the red and green lights pulsed — steady, unrelenting.

I closed my eyes tighter. Until everything had gone black.

Then I could hear bees.

Wind in tree branches.

A screen door creaking.

A woman humming, slicing salami in a cool, dim room.

I took another bite but didn’t chew.

The citrus lingered — not just as a taste, but as a scent, as a place.

I didn’t swallow. I just let it rest on my tongue, until it was gone.

—

Tim Carl is a Napa Valley-based photojournalist.

Poem of the Day

Spring

Frost-locked all the winter,

Seeds, and roots, and stones of fruits,

What shall make their sap ascend

That they may put forth shoots,

Tips of tender green,

Leaf, or blade, or sheath;

Telling of the hidden life

That breaks forth underneath,

Life nursed in its grave by Death.

Blows the thaw-wind pleasantly,

Drips the soaking rain,

By fits looks down the waking sun:

Young grass springs on the plain;

Young leaves clothe early hedgerow trees;

Seeds, and roots, and stones of fruits,

Swollen with sap, put forth their shoots;

Curled-headed ferns sprout in the lane;

Birds sing and pair again.

There is no time like Spring,

When life's alive in everything,

Before new nestlings sing,

Before cleft swallows speed their journey back

Along the trackless track, —

God guides their wing,

He spreads their table that they nothing lack,

Before the daisy grows a common flower,

Before the sun has power

To scorch the world up in his noontide hour.

There is no time like Spring,

Like Spring that passes by;

There is no life like Spring-life born to die,

Piercing the sod,

Clothing the uncouth clod,

Hatched in the nest,

Fledged on the windy bough,

Strong on the wing:

There is no time like Spring that passes by,

Now newly born, and now

Hastening to die.

About the Author: Christina Rossetti (1830–94) was born into a remarkable Anglo-Italian family of writers, artists and scholars. The youngest of four children, she grew up in London in a household steeped in literature, art and religious thought. Her father, Gabriele Rossetti, was a Dante scholar and political exile. Her mother, Frances Polidori, a former governess, educated the children at home. Christina’s brothers—Dante Gabriel and William Michael—became central figures in the Pre-Raphaelite movement, while her own poetic voice emerged early and proved both distinct and enduring.

Rossetti’s work blends the visual detail of the Pre-Raphaelites with the devotional tone of the Anglo-Catholic tradition. Her first commercially published book, "Goblin Market and Other Poems" (1862), established her as a major literary figure. Her poems often explore themes of renunciation, mortality, memory and divine love—sometimes through fantasy, sometimes through plainspoken reflection. Though often underestimated in her time, she is now widely regarded as one of the most skilled and emotionally resonant poets of the Victorian period.

The poem "Spring," drawn from her 1862 collection, reflects Rossetti’s sense of the season as a fleeting intersection between wonder and loss. Her lyric style — clear, restrained and quietly powerful — continues to resonate with readers more than a century after her death. Though often linked to her male contemporaries, Rossetti’s influence has only grown, especially as feminist criticism has illuminated her nuanced explorations of gender, faith and poetic voice.

Are you a poet, or do you have a favorite piece of verse you'd like to share? Napa Valley Features invites you to submit your poems for consideration in this series. Email your submissions to napavalleyfeatures@gmail.com with the subject line: "Poem of the Day Submission." Selected poets will receive a one-year paid subscription to Napa Valley Features (a $60 value). We can’t wait to hear from you.

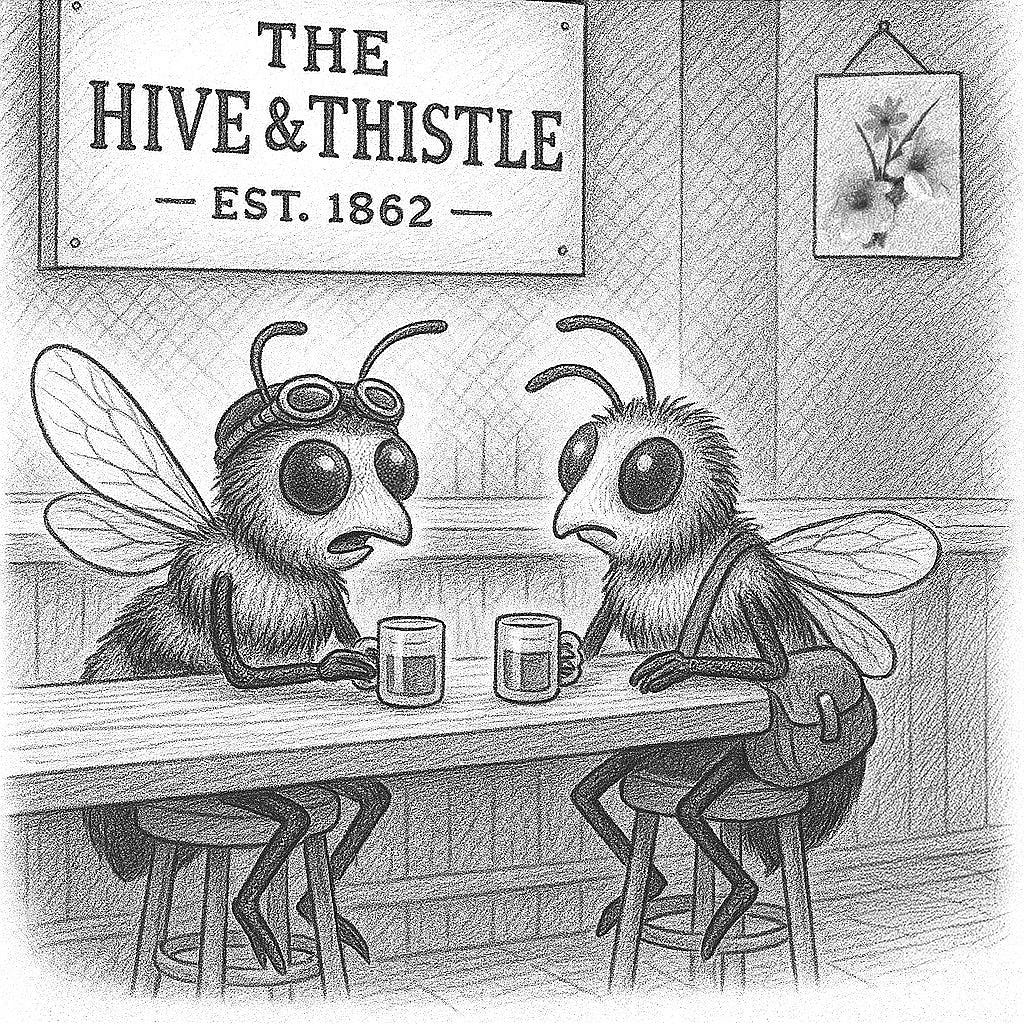

Today’s Caption Contest

Pick your favorite caption or add your own in the comments below.

Possible Captions:

"The orange blossom batch from '02? You can taste the rainfall."

"I used to fly for joy. Now I just fly for rent."

"I don’t want to talk about the chocolate bunny incident."

“The queen says I’m ‘too sensitive’ — like that’s a bad thing.”

“I keep dreaming about wax. Is that normal?”

Last week’s contest results

In “Sunday E-dition: Grave Concerns,” the winning caption was, “Remember, you're the bait. I'm the brains,” with 43% of the votes.

"OK, hold still — we’ll be airborne in no time."

"If this works, we open a school."

"One peep from you and we’re grounded."

“This will totally work."

"Remember, you're the bait. I'm the brains."

Last Week

Tim Carl reflected on the life of Fred Fisher in “Fred Fisher Has Died — A Quiet Force Behind a Family Legacy.” Fisher, who died this month, co-founded Fisher Vineyards with his wife, Juelle, helping to establish one of the few multigenerational, estate-grown family wineries spanning both Napa and Sonoma. A Detroit native with degrees from Princeton and Harvard, Fisher left a corporate path to build a winery rooted in hands-on farming and integrity. Known for avoiding the spotlight, he quietly shaped a legacy that continues through his children’s leadership and the family’s commitment to land and craft. His contributions also extended to education and advocacy for small wine producers.

Sasha Paulsen explored Paul Wagner’s latest novel in the Dan Courtwright Mystery series in her article “Grave Concerns.” Wagner, a Napa Valley author and longtime wilderness enthusiast, once again set his story in the High Sierras, where ranger Dan Courtwright investigates a string of disappearances tied to a rumored treasure hunt sparked by a popular mystery novelist. The plot follows a series of increasingly dangerous Search and Rescue missions as hikers pursue clues to a hidden cache of bitcoin, raising questions about the line between fiction and reality. Wagner emphasized that mysteries, unlike other genres, demand reader engagement and offer a layered exploration of place and justice. The novel also contains a concealed code that, according to Wagner, reveals an unresolved plot element.

Dan Berger examined wine faults and spoilage in “The Spoilage Spectrum,” for California Grapevine. He argued that while wine is celebrated as a cultural art form, it is also a complex chemical mixture vulnerable to flaws often overlooked by critics. Berger highlighted issues such as Brettanomyces, volatile acidity, diacetyl and mercaptans, noting their varied effects on aroma, flavor and perception. He also discussed winemaking practices such as filtration and cold stabilization, which might improve appearance but potentially diminish character. The column underscored the tension between technical control and preserving wine’s expressive depth.

Chris Benz reported on Napa’s efforts to bolster its environmental resilience in “Taking Care of Napa’s Trees.” Jeff Gittings, the city’s parks and urban forestry manager, is leading the development of a 40-year Urban Forestry Management Plan, beginning with an inventory of 35,000 community trees. The plan emphasizes expanding canopy coverage, increasing species diversity and engaging private property owners, whose trees account for 75% of urban forest coverage. Gittings highlighted the multiple benefits of trees, including cooling neighborhoods and improving public health, and underscored the importance of strategic species selection to guard against pests and disease. A draft of the plan is expected later this spring.

Tim Carl reported on the fallout from FEMA’s cancellation of its BRIC program in “Under the Hood: FEMA Pulled the Plug — Now What?” The decision revoked $35 million in federal wildfire prevention funding awarded to Napa County, halting a $50 million public-private initiative already in progress. County officials, including Supervisor Anne Cottrell, condemned the move as shortsighted and dangerous, citing Napa’s high wildfire risk and years of local investment. Despite the setback, Cottrell and other leaders met with federal agencies in Washington to advocate for legislative alternatives such as the Fix Our Forests Act. County staff are now evaluating legal and fiscal options to keep critical projects alive.

Donna Woodward of the UC Master Gardeners of Napa County shared insights into growing summer melons in “Melon Season Is Upon Us.” The group compared three melon varieties — Sugar Cube cantaloupe, Honey Orange honeydew and Alvaro Charentais — assessing their growth habits, flavor and suitability for local gardens. Sugar Cube proved the most productive and flavorful, while the Charentais fell short of its celebrated reputation. Success varied based on space and sunlight, with some gardeners reporting poor results. Woodward emphasized patience during ripening and offered guidance for home growers seeking a rewarding, heat-loving crop.

—

Beautiful, Carl. Time moving between two worlds, motionless, almost breathless in one, eternally familiar and beckoning in another. The breadth and depth of your work continues to impress.

Thank you.

Doug Murray

Tim, As always , held in deep suspense, lost in your world of words, senses enlivened and breathing suspended as you transport us into the core and soul of you and your experience. You are an inspiration of a life lived completely… and in exquisite references…