NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — That bottle of wine that catches your eye with a familiar brand name looks like a bargain and it may well be, but check the label to see where that branded bottle that you have trusted in the past is from.

It may not be what you think it is.

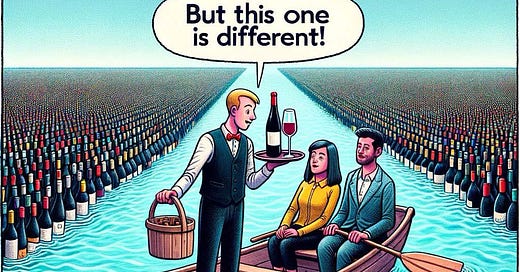

There is so much wine available throughout the world these days, California included, that everyone is thinking up ways to make use of some of the lower-priced excess to produce bottles of wine that have labels that look extremely familiar. In fact, those labels may well be identical to existing brands with pricier wines. Except for one thing: the place where the fruit came from may differ from what it has always been.

These brand extension wines (I call them Brand-X wines) frequently are sold at prices far below the cost of the primary company’s products – which carry extremely similar labels. Unsuspecting wine buyers may see a familiar product with labels identical to ones they have long been familiar with. But the difference is that instead of a quality appellation like “Sonoma County” or “Sonoma Coast,” the regional designation now says “California.”

Such a tactic allows for the blending in of significant amounts of wines from hot inland regions, where grapes are less expensive. That’s because they don’t make wines that are as good as the ones used for the same brand’s primary label that usually come from cooler coastal areas.

This allows a producer to charge a lot less for the wine, which often is proportionately less interesting.

Now this deterioration of quality has an even more pernicious aspect: we are seeing wines that might be carrying an even broader designation than California and may contain bulk wines from many thousands of miles away.

Industry experts say we are beginning to see wines with appellations that say “American,” not just “California.” Such wines may have up to 25% of wine from another country, including a country whose name isn’t pronounceable.

“I think some of these larger producers don’t want the consumer to care where the wine comes from.” - Stuart Spencer, executive director of the Lodi Winegrape Commission

Federal law permits this tactic. It permits an “American”-designated wine to contain as much as 25% imported wine. Which makes it that much more difficult for consumers to get a true handle on what kind of wine is in the bottle. And several experts now say that imported bulk wine today is a significant contributor to some lower-priced existing brands.

“I think some of these larger [wine] producers don’t want the consumer to care where the wine comes from,” said Stuart Spencer, executive director of the Lodi Winegrape Commission. “I think they want [their wines] to be brand-oriented, not place-oriented.”

Numerous grocery and wine stores sell well-known brands that have “American” appellations. I found a 2020 Apothic Inferno red wine, produced by E. & J. Gallo, at Safeway for $17.99. The bottle’s back label says this wine, which is aged in whiskey barrels, has 15.9% alcohol.

I also found a Beringer “Main and Vine” Cabernet Sauvignon listed as American, which sells for roughly $7 per bottle.

The authoritative San Francisco-based Gomberg-Fredrikson Report, using federal records, recently said that 68 million gallons of imported wine came into the United States in 2022 (almost all of it in bulk) compared with 51 million gallons in 2020. This contributed to an already massive oversupply of U.S. wine grapes and wine. The wine “lake” that has been created is so large that lower-priced wines are being discounted radically as wine buyers are shrinking in number.

Speaking with those in the industry, some believe that about 20% of all California wine grapes went un-harvested in 2023, mainly as a result of the oversupply. Prices remained higher than wineries could afford, based on sales projections, and without buyers, growers did not want to incur harvesting costs.

Joe Ciatti, the world’s most respected expert in the bulk wine market, said that roughly 400,000 tons of California wine grapes, largely in the central San Joaquin Valley, went unharvested last year because sales of wine, even at declining prices, are stagnant and inventories are growing. The wine surplus is mainly due to shrinking consumption. Many of those who once drank wine regularly now have switched to beverages with lower or zero alcohol.

Almost all agricultural crops go through over-supply, under-supply cycles. With wine it happens when demand exceeds supply and prices rise. Farmers see the imbalance between supply and demand, so many of them plant more of the crop that’s in short supply, which often then results, in a few years, in an oversupply. And then the cycle starts all over again.

“But it wasn’t over-planting [that created the current surplus],” Ciatti said, “because there really isn’t a lot of new plantings that went in. It is basically driven by less consumer demand, which isn’t normally an issue.”

Ciatti said the current wine glut may last longer than it usually does. “What needs to happen is [grape growers] got to pull grapes out of the ground. And that’s basically in the [Central] Valley – but that doesn’t mean there aren’t excesses on the Central Coast and in Mendocino and Lake County and even a little bit in Napa and Sonoma.”

Spencer in Lodi said all growers are aware of the cyclical nature of their business, “but what’s different now is it’s a global marketplace in bulk wine.” He said bulk wines from several countries are “easily moving around the world and it is eliminating the upside for a lot of California growers.”

Large wine companies are seeking lower prices for grapes because of the glut and Spencer said prices for Lodi fruit adjusted for inflation are declining. “I did a study on grape prices by crush district,” and he said Lodi growers are “getting about $.77 on the dollar that we were getting 10 years ago.”

He said, “I looked at various grocery store shelves and I’m seeing a lot of ‘American’-designated wine mixed in with the ‘California’-appellate wines.” It isn’t always uniform across the same lines of wine: “Some brands that you know, which are traditionally California-based, you’ll see a merlot and cabernet with ‘California’ on the front label, but the same brand’s pinot grigio doesn’t say where it’s from on the front label, and when you turn the bottle around, you find out that it’s either ‘American’ or ‘Product of Chile,’ or something like that.”

This is precisely the case with a Fetzer sauvignon blanc I found at Safeway. The front label gives only the brand name and the variety. Fetzer once was an enormously successful family-owned brand based in Hopland in Mendocino County. It subsequently was sold to a multi-national corporation. Turning that bottle around, I noted on the back label that the wine was from Chile.

Ciatti said that small wine producers can’t use this existing-image strategy.

“What’s happening is that our largest wine companies in California are evolving into global alcoholic beverage companies,” Spencer said. “They are leveraging their sales and distribution networks. … I think some of these larger producers don’t want the consumer to care where the wine comes from.”

“The big guys [producers] feel that the consumer doesn’t care if it’s ‘California’ or ‘American’ so they’re willing to replace [domestic grapes] with fruit or wine from Australia, or Argentina,” Ciatti said. “I think we’re destined to see more of the American appellation, and I think that’s really very sad.”

If today’s story captured your interest, explore these related articles:

Dan Berger's wine country chronicles: The power of pronunciation

Dan Berger's Varietal Views: Delving into riesling's complex profile

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

If the consumer is satisfied with the blended wines sadly, they don't care where the grapes come from. If the price is right also; it's just the ticket for that consumer. I don't drink wine anymore because my taste buds have changed dramatically with age. But when I did drink wine I would buy any Sauvignon Blanc from New Zealand. Never a miss and sooo much less expensive than Napa, Sonoma, Mendocino, etc. I have found that the labeling of olive oil has the same misleading labeling. Read the label and see where your Italian olive oil comes from. The "Product of Italy" is rarely 100% Italian olives. Spain, Egypt, Turkey, California are some of the contributors. Those oils can be delicious alone. Does the American consumer buy them separately? Marketing, cooking shows, and the Mediterranean Diet have made EVOO what to use but it can come from other countries besides Italy. Taste to the individual palette and the price to the individual budget are appealing to the "masses"; the mystic in a bottle of wine has been penetrated by the consumer. How often will a wine consumer reject a bottle of wine because it doesn't taste like the premium wine? How often did that consumer ever taste an expensive wine for comparison?

I read the labels and decide what I need the product for and what I want to pay for it.

as i traveled i found Chilean wines taste fine. I noticed last time I purchased many Napa wines are not all grown in Napa. I drink what tastes good. China has terrible tasting wine!!!