Collapse or Correction? Demographics and Labor at Play

By Tim Carl

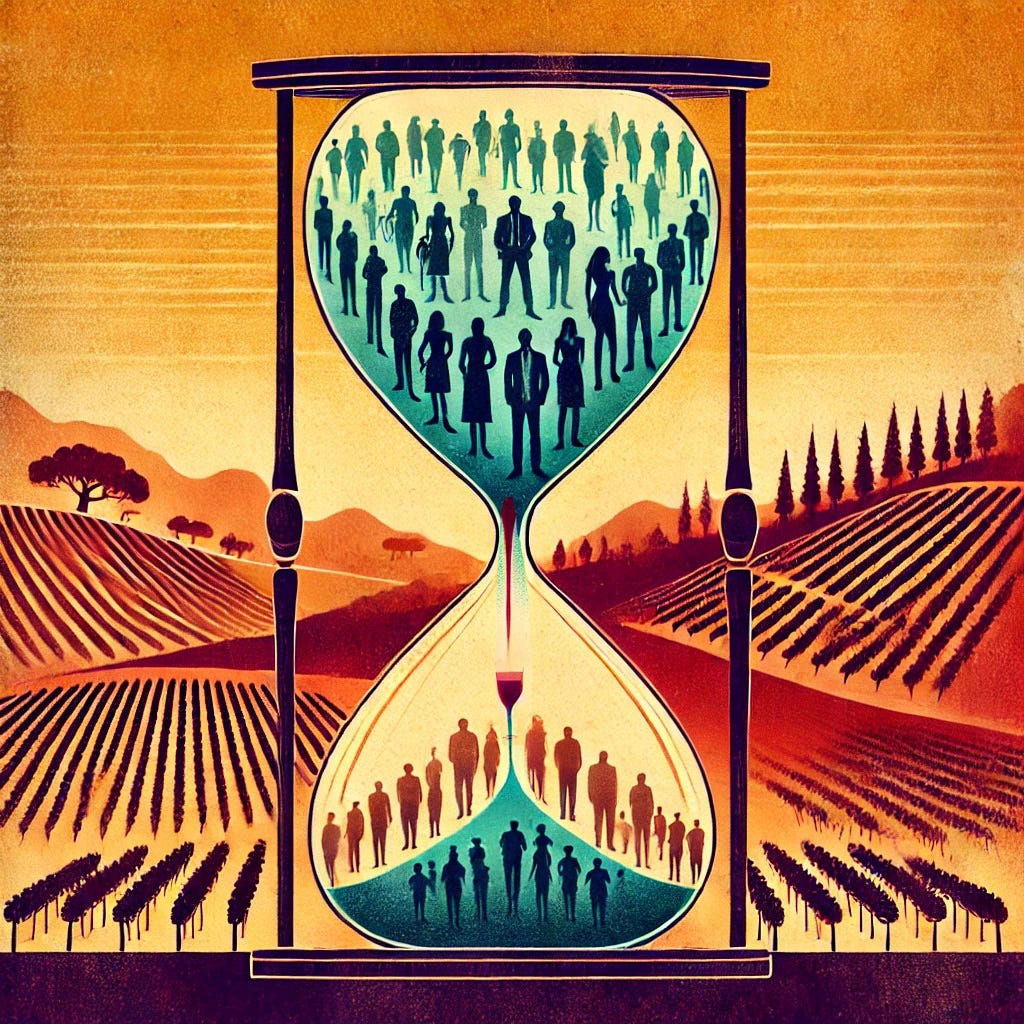

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — For those who believe the wine industry’s recent struggles are due to ineffective marketing, high prices or some ill-defined “neo-prohibitionist” forces, the following data presents a different picture. The industry's challenges are not simply about generating new demand — they are largely structural and population-based. These demographic shifts, briefly masked by an influx of easily accessible capital during the pandemic, are part of a broader, ongoing transformation. At the same time, Napa County's economy, heavily reliant on the wine industry, faces another significant challenge: an aging, shrinking local workforce that compounds the pressure on businesses and local governments.

The Rise and Fall of the Boomer Consumer Base

The success of Napa Valley and the wine industry over the past few decades can be traced back to three key factors: baby boomers’ interest in wine and luxury goods, their substantial disposable income and their sheer numbers. But these favorable conditions are no longer in place, and the industry is now facing a sustained period of decline.

The wine industry's challenges are not simply about generating new demand — they are largely structural and population-based, as an aging consumer base and changing generational preferences reshape the market.

In 2000, baby boomers were just entering their prime consumer years. The population pyramid from that year shows a bulge in the late 30s to early 40s. This group was not only large but also interested in luxury products, including premium wines and fine dining experiences. Boomers, with their disposable incomes, quickly became one of the most valuable customer segments for the wine industry.

By 2010, this consumer base had hit its peak. The boomers were in their 40s and 50s, the prime age range for purchasing luxury wines and indulging in experiences like high-end travel and Napa Valley tours. This was a time when the wine industry saw tremendous growth, driven by this generation's penchant for fine living and their ability to afford it. The 2010 pyramid shows the demographic bulge squarely in the prime spending years, fueling an explosion in demand for luxury products, including wine.

However, the 2020 pyramid tells a very different story. By this point, baby boomers had moved into their 60s and early 70s, ages when both the interest in and physical ability to consume alcohol start to diminish. Health concerns, decreased social activity and the body’s reduced ability to metabolize alcohol all lead to reductions in wine consumption. The boomers, who had long super-charged the industry, are no longer consuming wine at the levels they once did.

The Generation X “Pinch”

In contrast, Generation X, the cohort following the boomers, is far smaller in size, as shown by the narrowing of the population pyramid. The 2020 population data highlights this pinch. Gen X, now in their 40s and 50s, should ideally have stepped in to maintain the wine industry's momentum. However, they simply do not have the numbers to compensate for the steep decline in boomer consumption. The much smaller size of this generation leaves a gap that cannot be filled by traditional means like targeted marketing or price adjustments.

Millennials: A Delayed Economic Powerhouse

Looking ahead, many have pinned their hopes on millennials, a generation almost as large as the boomers. However, the economic circumstances of millennials are vastly different from their predecessors. Although the population pyramid shows that millennials have the potential to be a large consumer base, their economic trajectory is delayed.

Millennials carry the burden of student debt, stagnant wage growth and the economic aftershocks of the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors have collectively delayed their ability to accumulate wealth, purchase homes and, critically, spend on luxury items like premium wine. Millennials are simply not in a financial position to spend at the same levels that boomers did during their peak years. Moreover, their preferences tend to differ — many favor craft beers, spirits and experiences over traditional luxury goods like wine.

Even if millennials were as interested in wine and luxury experiences as the boomers were — and they are not — their economic maturity is delayed by at least five to seven years. Given their current financial constraints, the wine industry is looking at a decades-long decline. The demographic conditions that powered its boom are no longer in place. Gen X is too small to fill the gap, and millennials, while large in numbers, lack the financial firepower to fully support the industry in the near future.

The Exacerbating Effects of Napa Valley’s Aging Population

On top of these national demographic shifts, Napa Valley faces its own local challenges. While the broader U.S. wine industry grapples with population changes, Napa County’s local population is aging at an even faster rate. The 2020 to 2030 projections for Napa County show a clear trend: the population of those aged 18-64 — the prime working-age group — is expected to shrink from 83,614 to 67,032 by 2030, a drop of nearly 20%. This shrinking workforce is compounding the challenges already faced by businesses as the wine industry struggles with reduced demand.

At the same time, the population over 65 is expected to increase from 24,131 to 27,000, aligning with national trends but creating additional burdens on Napa Valley. This demographic shift increases the demand for healthcare services and strains local governments, which will need to allocate more resources to support an aging community while dealing with a shrinking tax base.

The accompanying demographic chart for Napa County illustrates these challenges, showing a steep decline in the working-age population alongside a rise in the aging population. This shift not only strains labor resources but also puts additional pressure on local governments and services to manage an aging population.

Pandemic Cash Flow Delayed the Wine Industry's Structural Decline

The effects of declining wine consumption were further masked during the pandemic by an unprecedented influx of cash into the economy. Consumers, confined to their homes and with fewer outlets for their disposable income, increased their wine consumption temporarily. The Wine Institute data show that the average consumption per capita rose to 3.12 gallons in 2020, the highest level in decades. However, this surge in demand was fueled by one-off factors: stimulus checks, easy credit and savings from reduced travel and leisure spending.

As these temporary effects wore off, the broader structural challenges returned. By 2023, per capita wine consumption had fallen to 2.68 gallons, a 14.1% decline from the pandemic peak. This drop-off highlights how the pandemic only briefly delayed the inevitable decline. The long-term effects of population shifts, aging consumers and changing generational preferences are now being felt, and the wine industry must contend with a shrinking base of regular wine consumers.

The graph detailing U.S. wine consumption from 1997 to 2023 underscores this pattern, showing a steady rise through the 2000s and 2010s before the post-pandemic decline became evident. The pandemic’s influx of easy capital temporarily masked the demographic shifts, but the underlying structural issues are now clear.

A Structural Shift with Long-Term Consequences

The wine industry’s golden years were built on the unique demographic conditions created by the baby boomer generation. As this generation ages out of the market and subsequent generations fail to fill their shoes, the industry is facing a long-term decline. And Napa Valley is hit twice — first by the shrinking national demand for wine and second by a rapidly aging local workforce.

The temporary surge in demand during the pandemic only delayed the inevitable. With millennials delayed by financial constraints and Gen X too small to maintain the wine industry's momentum, Napa Valley and the broader wine industry are facing a structural shift that will shape their future for decades to come. This isn’t a temporary dip, but a significant long-term challenge that requires a fundamental rethinking of how the industry operates.

For those who believe that building more affordable housing is the solution to Napa Valley’s workforce challenges, it’s important to consider the deeper structural issues at play. While housing remains a key concern, there is little evidence that large-scale affordable housing initiatives will resolve the core problem of attracting younger families and workers to an expensive area with limited family infrastructure. Without addressing the broader economic and demographic trends, Napa Valley will continue to face the dual challenge of a shrinking consumer base and a declining local workforce.

Ultimately, the wine industry, and Napa Valley in particular, must adapt to the shifting landscape brought on by demographic changes. The path forward requires innovation, new strategies and acceptance that the future will not mirror the past. The long-term decline in wine consumption is a structural reality, and the region must adjust if it is to thrive in the decades to come.

If today's story captured your interest, explore these related articles:

Under the Hood: Slowing Travel, Declining Wine Demand Threaten Napa Valley

Under the Hood: Deepening Crisis — Pressures Reshaping Napa Valley’s Wine Industry

Under the Hood: Napa Valley's Growing Reliance on the Wine Industry

Wine in Crisis: Navigating Prohibitionist Waves and Market Shifts

Under the Hood: A New Look at Workforce and Economic Development

Tim Carl is a Napa Valley-based photojournalist.

It’s as if no one expected the boomers to age and die off. I’ve watched the boomer blindness happen in other areas. There was once a frantic building of schools to accommodate the boomer bulge. Then the boomers aged out of school. Now school buildings sit empty and decaying, or even demolished. Perhaps the developers of the high end resort planned for the Krug land should be thinking in terms of a retirement community with assisted living accommodations rather than an expensive hotel. (I’m a couple of years older than the first boomers.)

Well done.