This article is part of our ongoing series examining Napa Valley's wine-based economy. In previous installments we explored the far-reaching consequences of supply and demand imbalances, and we have highlighted escalating legal conflicts, community tensions and business failures. We also discussed how flawed or incomplete data can undermine strategic decision-making and affect long-term sustainability. Additionally, we considered the rising probability of mergers and acquisitions, the declining impact of China on tourism and wine consumption, a recent surge in winery-license issuance and broad economic uncertainty. Today we investigate the consequences of declining and aging population, less real disposable income, changing tastes and a slowing global economy.

Please take a moment to fill out our short survey at the end.

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — California's original economy was essentially established by a gold rush. Since achieving statehood in 1850, figures such as Samuel Brannan, the founder of Calistoga and the state's inaugural millionaire from selling mining supplies, ultimately died penniless a few decades later. Similarly, the state's economy has oscillated between periods of boom and bust — from the California Gold Rush, 1848-1855, to the California land boom in the 1880s, the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s to early 2000s, the housing bubble in the mid-2000s and the green-tech bubble in the late 2000s to early 2010s. Since around 2000, Napa Valley has mirrored this pattern within the wine industry, with numerous new market entrants, soaring prices and a surge of speculative investors. Although many have thrived, signs indicate that Napa Valley is nearing the peak of what might be a sharp decline in the coming years.

Top-level findings in this article include:

Slowing population growth and aging demographics: Fewer luxury-wine consumers and altered spending are expected due to demographic shifts.

Changing disposable income: Transitioning from wages to investments has increased income volatility, affecting luxury spending.

Health advisories and preference shifts: Advisories for older adults to limit alcohol and changing tastes among younger consumers are moving preferences away from wine.

Investment challenges: The wine industry faces diminishing returns and heightened competition.

Economic trends: A global slowdown and deflation threats are on the rise.

Rising grape prices: Napa Valley's cabernet sauvignon grapes have seen a significant price increase, indicating speculative bubble traits.

Market competition: An increase in wine producers and competition, particularly in Napa Valley, intensifies market pressures.

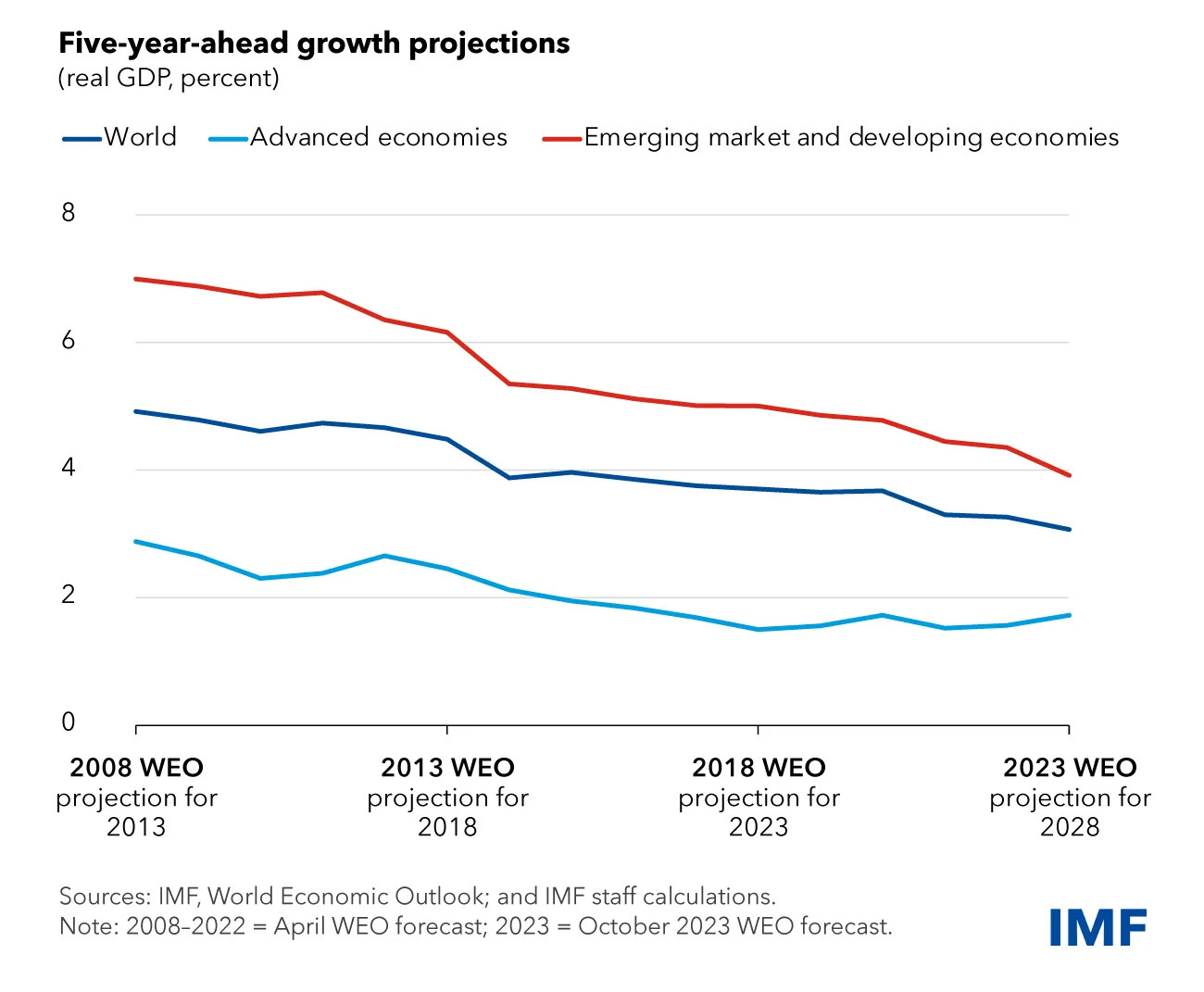

Global economic dynamics: International Monetary Fund projections suggest a slowdown.

Deflation's impact: Deflation can lead to recession and economic challenges.

Slowing population growth

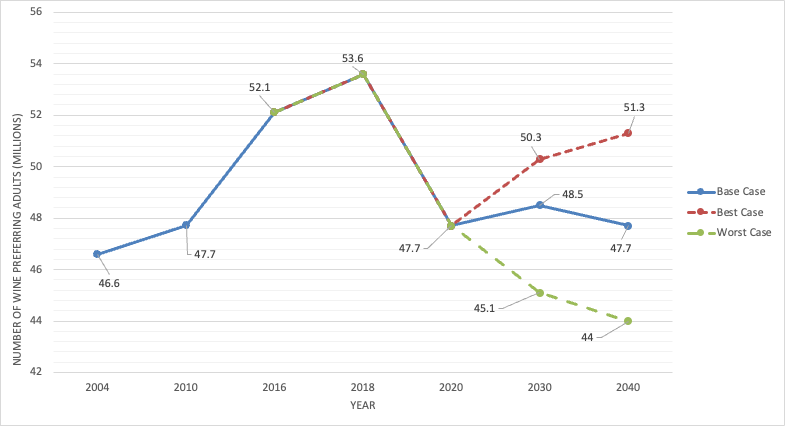

While the population was surging in California and the United States for most of the 20th century, starting in 2000 those numbers slowed significantly. For the wine industry these population trends have a 21-year lag phase. Thus, a surging population in the 1970s meant more potential wine consumers in the 1990s. However, slowing population growth in 2000 implies that the impact is just now being felt in the wine industry. This downward trend will accelerate.

Less real disposable income

Compounding the issue of population growth, from about 1980 to 2000 disposable incomes were increasing at the fastest pace on record. However, after 2000 the rate of change in disposable income slowed, with most personal wealth transitioning from wages to investments, such as real estate and equities. This shift has resulted in most personal wealth being closely linked not to wages earned but to investment gains, leading to increased volatility and spending habits tied to market volatility.

An aging population

The U.S. Census Bureau's projections for 2016 to 2060 forecast a significant increase in the population aged 65 and over. This growing demographic is expected to reshape spending patterns, with historical data indicating a tendency for reduced expenditure on luxury items, such as wine, as consumers age, as evidenced by the RAND Corp.'s finding that spending consistently declines after age 65 across all wealth groups, regardless of their economic status.

Additionally, the National Council on Aging suggests adults over 65 reduce or eliminate their alcohol consumption as changes in the body's ability to process alcohol and the heightened effects pose increased risks to this age group. This health-conscious perspective is expected to be adopted not only by the aging population but also increasingly by younger generations, with recent studies suggesting that no level of alcohol consumption is safe at any age.

Wealth concentration

Amid an evolving economic landscape, the generational wealth gap is becoming increasingly pronounced, with implications for luxury spending, including on fine wines and expensive travel/ restaurant visitations. In 2019 baby boomers commanded the most significant share of wealth at $59.4 trillion, significantly more than the assets of Generation X, the Silent Generation and millennials — each holding $28.6 trillion, $18.8 trillion and $5 trillion, respectively. Even during the pandemic, older boomers became $14 trillion richer, more so than any other generational cohort.

The Silent Generation members were born between 1928 and 1945 (currently 78 to 95 years old). Baby boomers were born between 1946 and 1964 (currently 59 to 77 years old). Generation X individuals were born between 1965 and 1980 (currently 43 to 58 years old). Millennials were born between 1981 and 1996 (currently 27 to 42 years old). Generation Z was born between 1997 and 2012 (currently 11 to 26 years old), representing the most recent cohort.

Despite baby boomers' dominance in wealth and their propensity for broad acceptance of ingesting intoxicants, their embrace of all things wine and their willingness to spend on luxury, their age is beginning to show in their consumption spending. Coupled with less disposable income across other generations, the impact on wine sales is set to accelerate.

Beyond this, the trajectory for alcohol consumption is shifting. Wine is becoming less preferred than spirits and beer, and economic concerns are now driving a moderation trend, with consumers opting to cut back on alcohol rather than down-trade, leading to reduced consumption occasions and quantities. This moderation is also notable in European markets, where economic consumer confidence is at record lows.

Changing tastes

For the last three decades, boomer consumers have embraced wine more than any other generation in U.S. history. This affinity has been a driving force in the wine market’s recent success, but as this generational cohort advances in age, their consumption patterns are expected to change, resulting in a decline in the overall wine market. Additionally, younger generations such as millennials and Gen Z have diversified palates, showing a preference for alternatives to wine. Even within wine itself they have shifted toward rosé and sparkling wines, often associated with more casual social drinking experiences. To highlight this change, a recent study suggested that half of all the beef consumed in the United States each day is eaten by just 12% of the population, predominantly white males between the ages of 50 and 65. This shift in preferences directly opposes the Napa Valley, where the majority of wine produced is from often expensive cabernet sauvignon grapes.

With boomers aging and their historically robust consumption of luxury products such as wine decreasing, even Gen X, millennials and Gen Z, with their varied tastes and financial constraints shaping their buying habits, are unlikely to make up the difference. Millennials, in particular, have been shaped by economic factors such as the 2008 financial crisis, the pandemic and slowing wage growth.

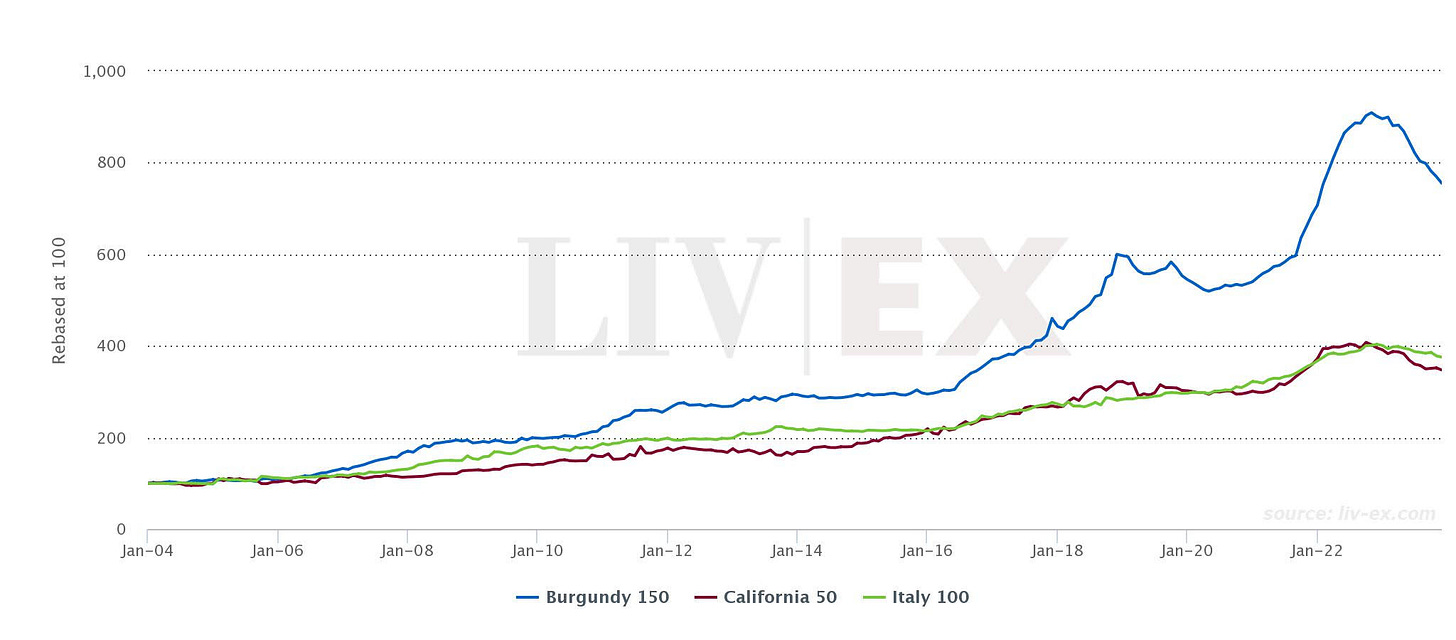

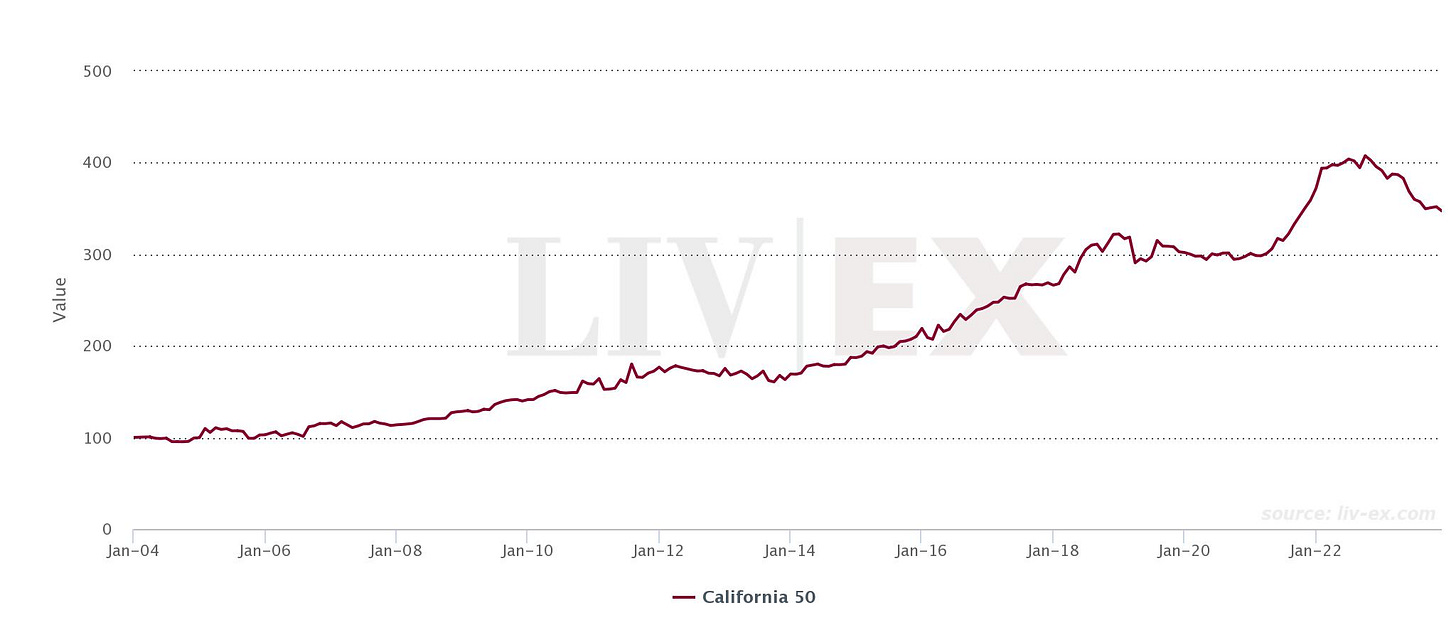

Volatile investment performance

Recent wine investments have soured. The "Liv-ex California 50" graph, which tracks the performance of top California wines, shows diminishing returns, reflecting market hesitation. There has also been a high-profile bankruptcy of the once highly prized Underground Cellar. Investors who once viewed wine as a lucrative haven are now facing a reality check.

The recent trends in the wine investment landscape, as indicated by the Liv-ex graph, point to the volatility of wine as an investment vehicle. Amidst economic uncertainties, while wine has traditionally been seen as a stable asset akin to gold or bonds, its allure is waning. This is exemplified by the underperformance of companies like Duckhorn Vineyards and Vintage Wine Estates, which have seen significant drops in share value post-IPO. The market's consolidation, with larger entities such as E. & J. Gallo acquiring boutique wineries, further complicates the investment picture, signaling a market that is increasingly difficult for smaller, independent producers and for investors looking for stable returns.

Sky-high grape prices

The astronomical rise in the price of a ton of cabernet sauvignon grapes in Napa Valley, which has seen an average increase from $461 per ton in 1976 to $8,813 in 2022 and a maximum price surge from $720 per ton in 1976 to $60,000 in 2022, reflects an astonishing 8,222% increase. This growth, averaging more than a 10% Compound Annual Growth Rate, mirrors the trajectories of notorious speculative bubbles. Moreover, the price differential between the average and maximum price of these grapes has dramatically risen from 56% in 1976 to more than 580% in 2022.

The sorts of growth rates highlighted in this chart and the differentials are comparable to the trajectories of infamous speculative bubbles. For instance, the 2008 housing-market bubble witnessed colossal failures such as Lehman Bros. The dramatic rise and fall in mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations were major factors in the 2008 financial crisis, providing a stark comparison. Private bond issuance of MBS and CDOs peaked at close to $2 trillion in 2006 but plummeted to less than $150 billion by 2009. Additionally, the amount of MBS issued nearly tripled from 1996 to 2007, reaching $7.3 trillion, with the securitized share of subprime mortgages rising sharply from 54% in 2001 to 75% in 2006. At its lowest point, this market contracted to less than $4 trillion in the aftermath of the financial crisis. Even Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme only promised annual returns of around 10% on investments, not the compounded annual growth rates of 10%, which is in the realm of the impossible.

Crowded market

Competition is fiercer than ever. The number of wine producers continues to increase by about 4% per year. With more players in the field, the fight for market share is intensifying, and not all are likely to survive. This growth has been particularly dramatic in Napa Valley, where the number of Type 02 winery licenses (needed to have a winery but can also be used by wineries for secondary sites, tasting rooms and even warehouses) holds a disproportionate number of Type 02 licenses — more than 27%, although it only produces 4% of the state’s wine.

And here we are only talking about U.S. wine brands. When considering the entire world — even though overall production has remained relatively flat as consumption has declined — the actual number of global wine brands is estimated to have grown since 2000.

Global economic dynamics

To exacerbate these trends toward slowing growth of wine consumption, a global economic slowdown is expected over the next five years, based on projections by the IMF. According to the IMF's findings, world economic growth is likely to decrease from 3.5 percent in 2022 to 2.9 percent by 2024. This downward trend in growth is a result of various ongoing challenges, including the lingering impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical tensions such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and the persistence of pricing shocks (both inflationary and deflationary).

The specter of deflation

While runaway inflation in any economy is detrimental, precipitant deflation is worse. In short, as prices drop, companies are unable to increase wages or investments, and this might lead to the cutting of jobs and services. This is especially problematic when prices for imported goods continue to rise.

Deflation in economics refers to a sustained and widespread decrease in the overall prices of goods and services within an economy, essentially the opposite of inflation. It's not just a one-time drop in prices; it occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0%, indicating that prices are consistently falling across the board. While lower prices might initially seem beneficial, deflation can have severe consequences. Several factors can contribute to deflation, including reduced consumer demand, an oversupply of goods and services, technological innovations that lower production costs, and certain government policies such as reduced public spending or higher interest rates.

For businesses, navigating deflation can be challenging. Decreasing prices can lead to reduced consumer spending and profitability challenges. Additionally, the real value of debt increases, making it harder for businesses to repay loans. To counteract deflation, central banks often implement monetary policies such as lowering interest rates or increasing government spending. Historical examples of deflation include the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s and Japan's "Lost Decade" in the 1990s.

Tipping point

The wine industry is at a tipping point. The convergence of an aging population and decelerating population growth signals a future with fewer consumers on the hunt for expensive wine, dining and other discretionary luxury experiences, while the varied tastes and financial constraints of younger generations foreshadow a drastically different market landscape. The wine industry, once a secure investment, is now grappling with the likelihood of diminishing returns, exacerbated by astronomical grape prices and intense market competition.

Confronted with global economic challenges, including an anticipated slowdown and the threat of deflationary pricing pressures, the Napa Valley finds itself at a crucial intersection. In light of these profound shifts, it is imperative for the community to acknowledge and engage with these new circumstances, innovating and adapting strategies to preserve its rich heritage and thrive in an evolving reality.

Tim Carl is a Napa Valley-based photojournalist.

Welcome to our survey on Napa Valley's future. We value your insights on finding a balance between agriculture and tourism. Please share your thoughts in the space provided below. If you have detailed comments, kindly use the comment section. For submitting letters to the editor, please fill out our online form. Additionally, if you wish to submit story ideas, you can do so using this form. We appreciate your participation. Please read each question carefully, as you can only select one answer and cannot go back to change your responses. Thank you for contributing to this important discussion.

Tim

Solid stuff! My other comments: Biggest threat remedy--Threat is Napa is pricing itself out of relevance, and appeal/affordability to anyone other than elitist consumers with lots of money. Manage economic slowdown: re-direct producers/marketing to making Napa once again a place with wines that can be enjoyed for a sensible price, and re-imagine the winery experience that doesn't simply appeal to well-off day trippers. Tied into all of that. Napa producers must re-think their continuously greater super-premiumization of their portfolio. Ironically, one solution would be if current and new owners were extremely wealthy enough to operate production in such a manner that the price of wines can come down to more manageable affordable and more widely available levels. Publicly owned wineries in Napa cannot remain viable, therefore.

OR- we just accept the fact that except for the well-off, the expense account crowd and wine critic geeks (will include myself), Napa can no longer remain of interest. It will become a smaller, niche region that is off the radar for most consumers. It will survive and prosper within a smaller 'neighborhood'; sort of the way Wagyu Beef producers do Joel

I realize the math is complex (land prices + production costs + marketing + etc.), but I think a lot of producers are simply pricing themselves out of the market. A bottle of top-shelf liquor yields ±18 cocktails for the same cost as only five glasses of a moderately-priced Napa wine, so it's no wonder younger adults are discovering the joy of mixology. BTW, plenty of Boomers who could easily afford Napa Valley price tags just aren't interested in over-spending on what is frequently just hype ... even my friend who has Rockefeller-level wealth often rolls his eyes at Napa prices and opts for an excellent 'new-world' or 'old-world wine' at a fraction of the price. Turning our beautiful valley into a wine 'Disneyland' where even well-paid locals can't afford houses is a nightmare scenario that could easily come to pass.