Winiarski is honored by the Julia Child Foundation

By Sasha Paulsen

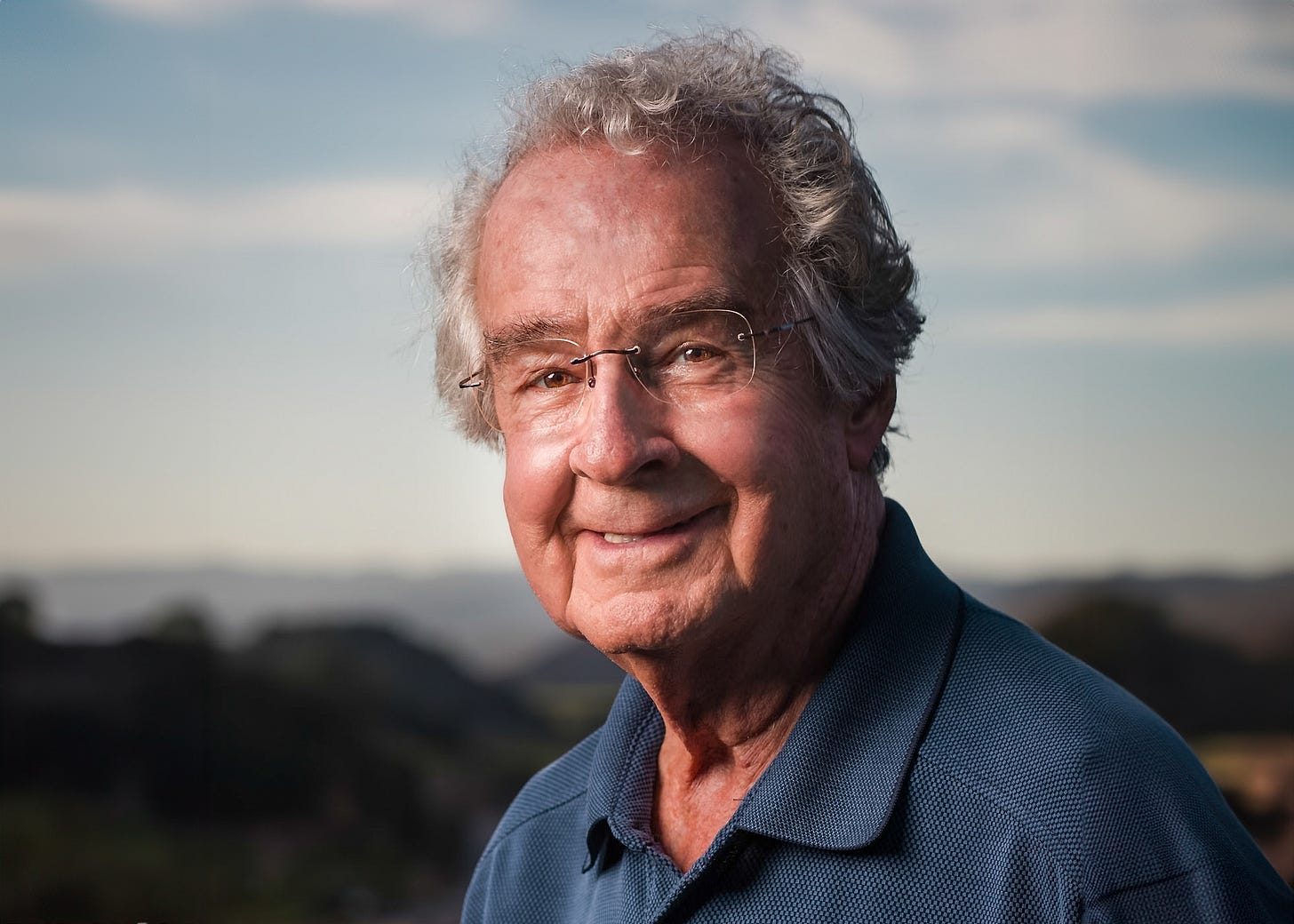

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Warren Winiarski’s receiving an award is not exactly news. Over his six-decade career in the wine industry, the venerable Napa Valley vintner has received enough accolades to fill several volumes. He has been lauded not just for his winemaking but for his contributions to education, conservation and the valley he calls home.

These range from a 1997 award in Paris as one of the “30 greatest winemakers in the world” to being named, with his late wife, Barbara, the 2008 Grandparents of the Year in Napa County.

His newest honor arrived on Feb. 29, when The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts awarded Winiarski, 96, the inaugural Trustee Medal of Honor.

“There is no one more deserving of this first-ever award,” said Eric W. Spivey, chairman of the foundation. “It was established so the foundation’s trustees could recognize those who have made an enduring lifetime contribution in the fields of gastronomy and the culinary arts.”

In true Winiarski style, the award became the occasion for a party with friends and a fundraiser for one of his favorite causes, the Smithsonian Food History Project.

The dinner in the wine caves of Stags’ Leap Wine Cellars was also the kickoff of an online auction supporting the Smithsonian project to view food through the lens of history. Among its lots is Winiarski’s donation of a bottle of the wine that won him another honor. That would be the 1973 cabernet sauvignon that went to Paris, bested the best of the French red wines in a blind tasting and turned the wine world on its head. Along with the chardonnay made by Miljenko “Mike” Grgich, which won top ratings for a white wine, the two Napa Valley wines brought international attention to California wines and inspired winemakers to make wines that could hold their own with France’s fabled wines.

Eleven bottles of Winiarski’s 1973 cab remain in his cellar. He is giving one signed bottle to the auction, along with a copy of the Smithsonian’s “History of America in 101 Objects.” Two bottles, the red and the white, from the tasting that came to be known as the Judgment of Paris, are among those 101 objects.

The silent auction, which includes donations from “a who’s who of Napa Valley winemakers” is open to the public online through March 8. View the full list of entries and place bids here.

Winiarski has been involved with the Smithsonian since 1996, when he called to ask how the museum would be honoring the 20th anniversary of the Judgement of Paris and its impact on American life and culture. Since then, he and his late wife, Barbara, have supported the Smithsonian Food and Wine History Project, providing a bequest to endow a full-time curator position for it.

In 2017, the Smithsonian awarded Winiarski the James Smithson Medal, established in 1965 and given to those who have made “exceptional contributions to art, science, history, education and technology.” Queen Elizabeth II, Pope John Paul II, Stephen Hawking, Dave Brubeck, Walter Cronkite and Sir Edmund Hillary are among the other recipients.

Last year marked Winiarski’s 60th harvest since the young professor at the University of Chicago who had discovered wine while researching Niccolo Machiavelli in Florence, Italy, packed up his family and drove across the county to the then-unknown Napa Valley. Talking about a wine that sparked his decision, Winiarski once said, simply, “It spoke to me.”

Winiarski’s goal, then as now, is to achieve the “sense of completeness that makes a beautiful wine.” But as he created his “iron fist in a velvet glove” wines, he worked to restore wine’s standing in America after the damage done by Prohibition. He found a peer and kindred spirit in Julia Child, who transformed the American table with her lessons from “The French Chef.”

“Julia held Warren in such high regard for his achievements in elevating wine and winemaking,” said Spivey, who shared a clip of “Dinner With Julia” from January 1984, when Winiarski paired his wines with her menu at a dinner party. Interestingly, among his choices were a Napa Valley riesling, merlot and gamay Beaujolais.

That Winiarski held Child in mutual esteem was evident in one of the items on display at the dinner in the winery he and Barbara built in 1973: a small traveling kitchen Child used for demonstrations. Child’s kitchen from her Massachusetts home is now part of the Smithsonian collection.

“Her kitchen symbolizes exactly what she stood for: a gracious and familiar way to access the elevation of food from merely nutrition to something beautiful, something that satisfies another part of our soul,” Winiarski said.

In 2018, Gov. Edmund Brown inducted Winiarski into the California Hall of Fame for his global efforts to showcase California wines and to preserve their history. That same year Wine Enthusiast magazine named him an American Wine Legend. He has long been a member of the Culinary Institute of American’s Vintners Hall of Fame.

But as he garners honors on a global scale — in 2017 he was named Person of the Year by Czas Wina Magazine in Poland, and he received the Grand Award for Lifetime Contributions to Wine Education from the Society of Wine Educators in 2017 — Winiarski has also kept his focus local. His work goes back to 1968, when he was a supporter of the Ag Preserve, the land-zoning ordinance that established agriculture and open space as the highest and best use for the Napa Valley, essentially preserving the landscape we see today. Among his other causes are the Queen of the Valley hospital and If Given a Chance, which supports students who have overcome severe challenges to find a path to college. In 2022, UC Davis named him a Distinguished Alumni of the Year for his support of their wine library and other enology and viticulture programs.

A list of all awards can be found at this link.

Although he gave up his job as a professor for wine, Winiarski has continued to teach. Not only did he return to his alma mater, St. John’s College, to teach summer sessions in classics, but he also served as a mentor to new generations of winemakers.

Several of Winiarski’s students were on hand at the February dinner to share their experiences. John Kongsgaard, who came to Stags’ Leap Wine Cellars as an aspiring winemaker in 1977, recalled that one of his first assignments from Winiarski was to install a new linoleum floor in the bathroom of the estate manager.

Winiarski later explained the task: “I said, ‘Before I let you make my wine, I need to know who you are.’”

He and Winiarski became lifelong friends, Kongsgaard told the audience. He went on to found his own Kongsgaard Winery on Atlas Peak, and after he lost his grapes in the 2017 wildfires, he asked if he could buy some of Winiarski’s harvest. Instead, Winiarski gave him the grapes from his prime vineyard in Coombsville.

Michael Silacci, now the longtime winemaker at Opus One winery, recalled riding with Winiarski, who while driving “like a bat out of hell” asked if he would like a cup of coffee, then gave him three coffee beans to chew on. The Julia Child Foundation award, Silacci said, “is a well-deserved honor for your inspiring, enduring example to the wine industry.”

“You changed my life and you changed the lives of so many,” another Winiarski student, John Williams of Frog’s Leap Winery, said in a taped message.

Although Winiarski was unable to attend the party on the stormy February night, earlier in the day he met with Spivey, who presented him with his new medal, “in recognition of a lifetime creating long-lasting change in the world of American food and wine.”

Winiarski responded, “I was doing what I liked, and so it was no burden.”

If today’s story captured your interest, explore these related articles:

Three Napa Valley women champion arts and community projects

The Silverado Trail Strawberry Stand: Cultivating a Flavorful Legacy

The master cookie-maker of Marseille and other tales from the Vallée de la Gastronomie

Sasha Paulsen is a journalist and novelist who lives in Napa.

.jpg)