NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — As a professional journalist, I was educated to be suspicious. My wife understood my almost compulsive skepticism; many of my friends believe that I’m simply paranoid. But this character trait has occasionally saved me money, and it certainly has been a benefit when we have been out to dine and simply want a glass of wine, so I order something from the by-the-glass menu.

Pitfalls seem inevitable.

Before launching into this diatribe against the generally woeful quality of most by-the-glass wines, I must explain that I do believe that restaurants that sell wines by the glass generally consider this to be a legal (yet I believe unethical) bit of highway robbery. Here’s a brief explanation.

A restaurant patron (or a party) is seated. A server asks if they would like something to drink. For some Americans who were naïve and inexperienced about wine, the most common response in the 1970s was, “A glass of Chablis,” which was “upgraded” in the 1980s and 1990s to “a glass of chardonnay,” as if this was a major improvement. (It was not.)

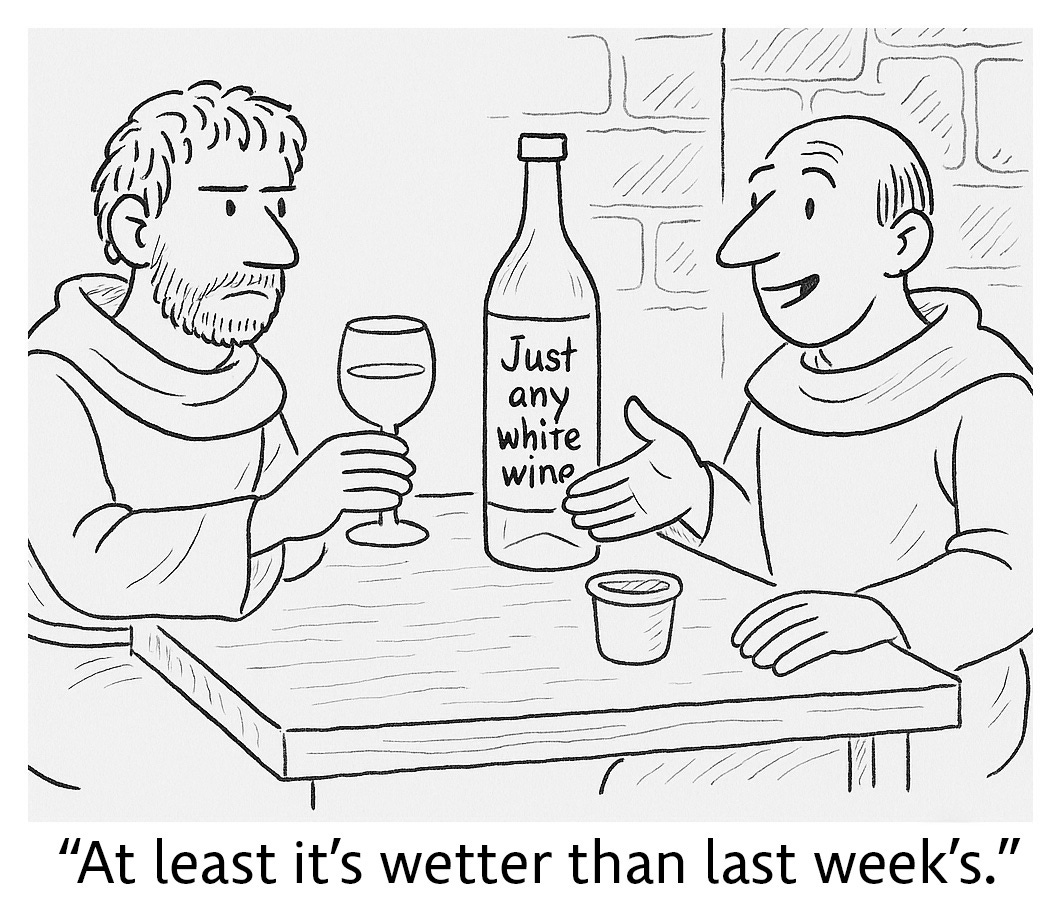

Clarification: Almost no one back then ordered a glass of anything other than a white wine, and the requested Chablis in the first reference probably deserved a lowercase c because it rarely came from the French district of Chablis. When chardonnay became the standard request, it started out actually coming from the chardonnay grape. However, in most latter-day situations, any random white wine would satisfy the requirement for most of the people who ordered “a glass of chardonnay.”

"Never, in my experience, have I gotten a wine that was better than what I had ordered. It has always been worse."

Even if the wine was a completely bland generic white wine, some people were satisfied with it — as long as it was relatively wet. It didn’t have to smell or taste like chardonnay to satisfy the requirement, which led to many wineries producing chardonnays that had absolutely nothing to do with chardonnay. By the mid 1990s, the word “rosé” was added to the by-the-glass lexicon.

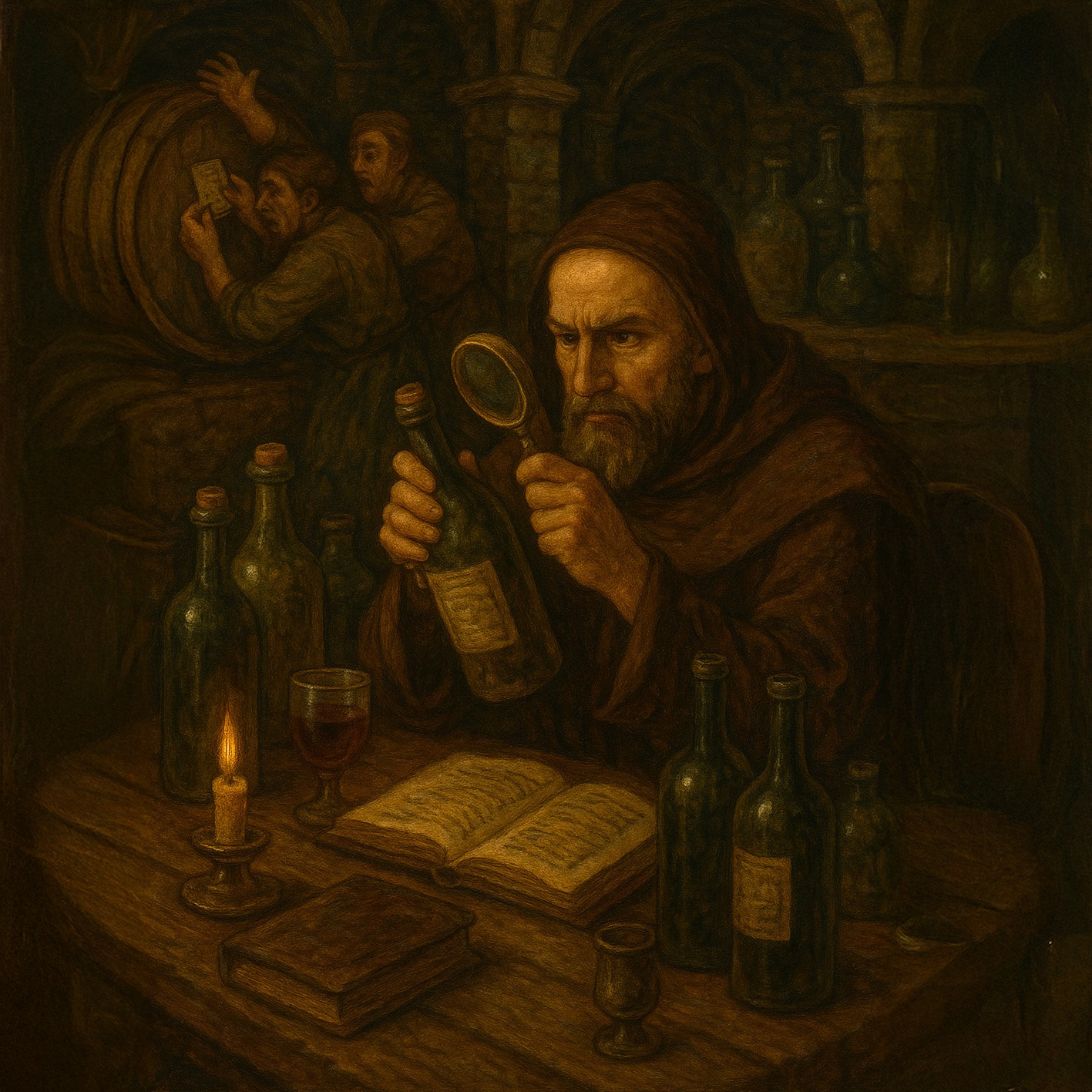

I began paying attention to this by-the-glass category, which I began to see as merely vinous prestidigitation, in the early 1980s, shortly after I began writing about wine, when it was obvious that some of the wines I was being served in restaurants had not even a passing resemblance to what I had ordered. And it became obvious that the practice of “bait and switch” was widespread because some restaurants were hiding behind a tactic that seems to have been designed specifically for vinous deception.

It certainly did not help when some of the wines I got smelled more like bait.

The odious tactic that restaurants hid behind was obfuscation. In almost all cases, when you order a glass of wine, the server does not present you with visual proof that the glass you got is actually the wine you ordered. This chicanery appears to be widespread because this little bit of dishonesty is not even listed in the penal code as a misdemeanor. To many restaurateurs it’s simply standard operating procedure.

And the reason that this cynical bit of cheating appears to be so rampant is the confluence of two universal dictums:

Many American wine-drinkers don’t know how to taste a wine and make an accurate judgment about it.

In more than 50 years of writing about wine and observing it up-close in restaurants from Napa to Ljubljana, I have never seen a single by-the-glass orderer ask to see the label of the bottle from which their glass was drizzled. Doing so might imply that the patron is skeptical and that the eatery is acting fraudulently, heaven forbid.

One more reason that the practice is so widespread is that restaurants know they are unlikely to be caught cheating.

When I order a wine by the glass, I often ask to see the bottle – much to the irritation of servers. I consider it to be due diligence. And what I discovered, in many different instances, was outrageous smoke-screening that usually boiled down to a blatant attempt to charge more for a glass of something that was supposed to be one thing but was another. In most cases, the unsuspecting patron is given a much cheaper substitute.

Result: the restaurant makes more money.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

And why am I so cynical? Very simply it is that never, in my experience, have I gotten a wine that was better than what I had ordered. It has always been worse.

The rest of this column could well be devoted to a dozen case examples replete with what restaurant employees told me was either “an honest mistake” (uh, sure) or “a better wine than I ordered” (no) or “We’re out of what you ordered” (right) or “That’s what the bartender gave me” (really?).

Establishments where this has not occurred with any regularity are small cafés or places that call themselves wine bars, but fraud has occurred in those places, as well. Double-dealing has occurred to me in modest places and fancy. But never in a Michelin-starred restaurant, where it is assumed that some (wealthy) diners might be well-versed in wine and their patronage should never be jeopardized.

One early bad episode occurred in the restaurant at the Hilton Hotel in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in about 1990. I ordered a glass of cabernet, whose producer was listed on the wine list. What arrived was not cabernet. It was a very poor-quality, slightly oxidized Beaujolais. It was undrinkable. The frazzled waiter finally brought the bottle to me. It was about as bad a choice as I had ever seen.

He then went back to the bar and returned with a glass that smelled like a cabernet, but it had nothing to do with the brand on the wine list that I had ordered. I asked to see that bottle too. It was a closeout. I switched to beer.

Perhaps my best experience with a by-the-glass wine was when I took two of my sons to lunch at the late, lamented Windows on the World restaurant on the 107th floor of the north tower of the World Trade Center in New York City. It was in the early 1990s. An old friend, the brilliant wine director Kevin Zraly, was in the dining room.

I wanted a glass of red wine. That day the special was 1981 Château Haut-Brion—which Kevin opened and then poured for each diner directly from a pre-decanted bottle.

Similarly, at a modest Melbourne wine bar/coffee shop in 1999, my wife and I ordered different wines. The proprietor brought both bottles to our table and poured from them. I asked him if that was his standard practice. “Always,” he said, adding that he hated it when restaurants served something other than what is advertised.

One of the wines was red. I asked him when the bottle was opened. I was concerned that the wine might have been opened a day or two earlier and was then slightly oxidized.

“We open new bottles every day,” he said.

I asked him what happened at the end of the day when there was perhaps a half bottle of red remaining.

“We give it to our staff to take home,” he said. “I don’t trust red wines that have been open for more than half a day.” What an enlightened attitude!

An entire book could easily be written about by-the-glass wines. One basic “rule” of the restaurant business is that typically the price of a glass is calculated by how much the bottle of wine costs the restaurant. The glass price equals the restaurant cost for the bottle. Say a bottle has a suggested retail price of $38 at full markup. The bottle costs the restaurant about $24 – so that’s how much a glass of it would cost diners.

Until the unbelievably depressing downturn in wine sales throughout the United States this year, this “formula” was commonplace. But since wine is not selling these days, you would expect that restaurants would change their by-the-glass pricing strategy. It makes logical sense.

But in the last year, I have noticed that by-the-glass pricing seems to be unchanged, making a glass of wine almost prohibitive for one particularly good reason: Restaurants have gotten into the habit of charging more for a glass then the entire bottle cost them. That $24 wine mentioned above is now $28 in many different locations.

It is true, of course, that restaurants frequently get a discount if they agree to pour a particular wine by the glass, so the glass above is probably being sold for a lot more than the bottle cost the restaurant. And if the price went up to $28, the restaurant makes that much more money – IF it can sell the wine.

Now for a few suggestions on how to order wine in a restaurant:

Vintages: Determine if the vintage that’s on the list is what’s also on the bottle. If you ordered a 2024 rosé and the wine seems to be a little tired, ask to see the label to make certain that the wine is not from an earlier vintage. (A lot of 2022 and 2023 rosés are currently being closed out, and my suspicious nature …)

Day-old reds: I almost never order red wines by the glass in a restaurant unless I can see the label because bottles that were opened the day before or even earlier might have been left on a counter, unrefrigerated, and could be oxidized. (Tip: Some red wines will improve with aeration, but only to a point. At home, I refrigerate opened reds. When I want to try them again, I remove them from the refrigerator and let them warm up on the counter. Almost no restaurant does this.)

(Tale: In a New York hotel bar in 2003, five red wines sat on a counter. It was 4 p.m., and I was the only patron at the bar. I asked the bartender how long the bottles had been open. He shrugged. I said I’d like to try a glass of a particular Bordeaux but I needed to smell it first. He handed me the bottle. I pulled the cork. The wine was badly oxidized. I asked the bartender if he could open a fresh bottle. He said he would – after the one I was holding was empty. I asked him if he had a sink.)

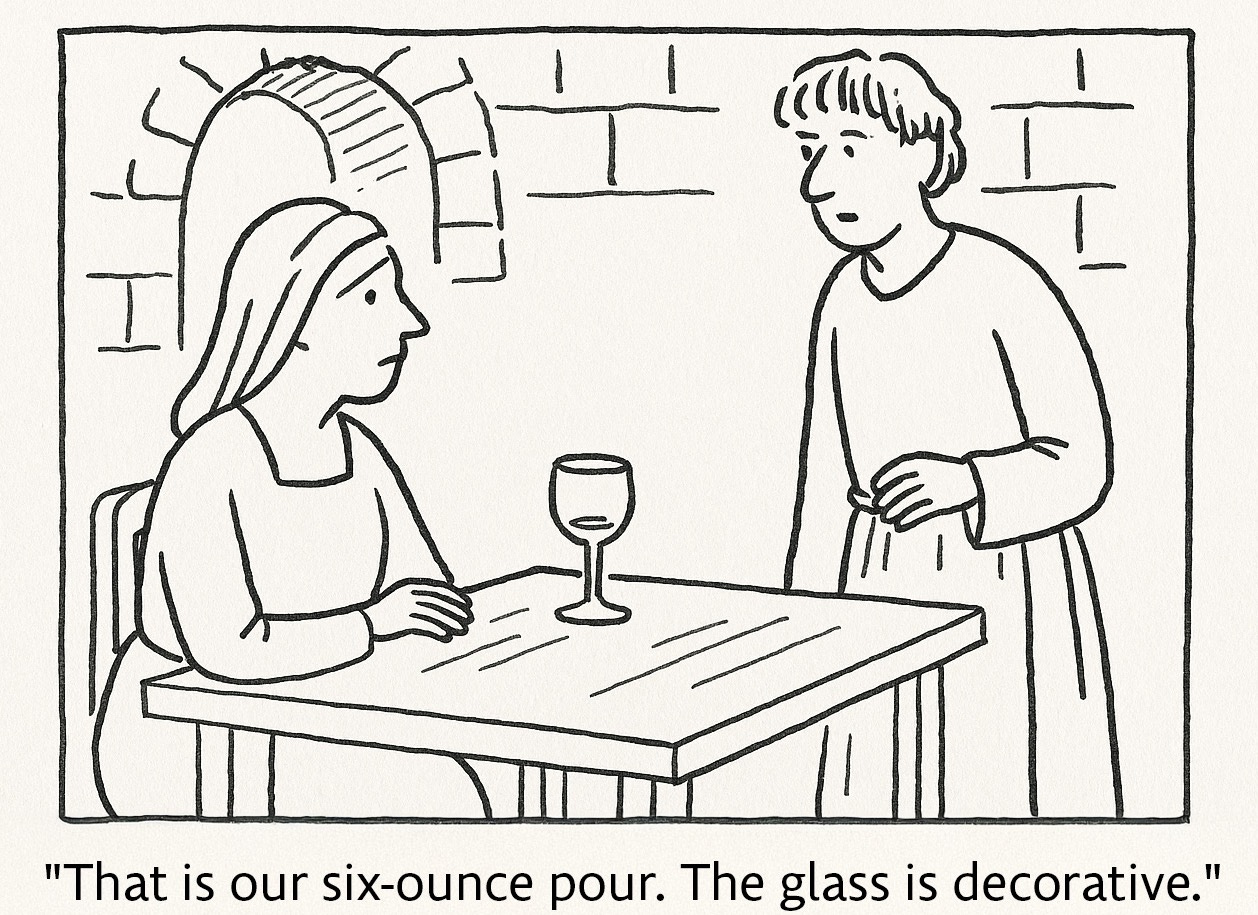

Standard pours: A standard bottle of wine contains roughly 25 ounces, which equates to four 6-ounce pours. Some restaurants use glasses that, even when filled to the rim, contain only 4.5 or 5 ounces. Decades ago I did a random survey of restaurants in San Diego. About 25% of them were pouring roughly 5 ounces of wine in a “standard glass,” not 6 ounces. This gave them one extra pour per bottle.

Sparkling wines: In the early 1990s, when I was doing restaurant wine-list reviews for the Los Angeles Times, I carried a small measuring cup and found that approximately 50% of the restaurants I went to were serving just over 4 ounces of sparkling wine in glasses that were filled to the rim. I suspect that the glasses had been chosen specifically because they gave the restaurant extra pours. Diners were being deceived because the glasses appeared to be full.

Chilling: One tactic that I’m not certain is an attempt to deceive is simply the chilling of white wines to the point where they are so cold diners can’t smell anything. The colder a wine is the less likely it is to display its normal aroma. At that time I carried a small wine thermometer when doing restaurant wine-list reviews. I discovered that in most cases white wines were being served at around 40 degrees, which is far too cold for almost any white wine. (At an upscale Chicago lounge one afternoon, I ordered a glass of sauvignon blanc. It arrived with ice shards floating on top.)

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

—

Wine Discovery:

2024 ALAS VINI Sauvignon Blanc, North Coast ($48) – When a wine is made with a European sensibility using California fruit in the Napa Valley by a winemaker who has a history of making wine in Italy, the result can be intriguing. This wine is exactly that. Aromatically it is delicately tropical, with varietal hints of wildflowers and the subtle influence of dried and fresh herbs. A day after the cork was pulled, the wine was even more interesting, with a slight creamy character from extremely careful barrel-aging. There is also excellent acidity and good balance. ALAS VINI was founded in the Napa Valley by Alberto Giusti, who worked in Italy before moving here. The name is an acronym of Alberto, his wife and children (Alberto, Leo, Ashleigh, Stella). — Dan Berger

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is C: "A deceptive seller or fraud." The word "mountebank" first entered English in the late 16th century, borrowed from the Italian montimbanco — itself a contraction of monta in banco, meaning "to mount a bench." The term originally described street performers who would climb atop benches in public squares to hawk dubious cures, potions and miracle remedies, often with great theatrical flair. Over time, "mountebank" broadened to refer to any charlatan or fraud — someone who deceives or swindles others for personal gain.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.

Having been in the restaurant business in California for 30 years, I don't think I have ever been so offended by someone who is supposed to be a wine professional. You have laid us all out to be liars and thieves...kiss my ass Dan.

Tim Seberson

Kitchen Door, Napa

I suddenly feel gullible...