NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Today’s Napa Valley wouldn’t be the same without the numerous Chinese laborers who immigrated here between 1870 and 1900. They were just one ethnic group who left their countries and came to the Napa Valley.

Immigration into the Napa Valley from 1820 to 1920 is the subject of two exhibits, one at the Napa County Historical Society’s Goodman Library in Napa and the other at the St. Helena Historical Society’s Heritage Center, 1255 Oak Ave. in St. Helena. The two groups collaborated on the exhibits, which are funded by an Arts Council Napa Valley grant.

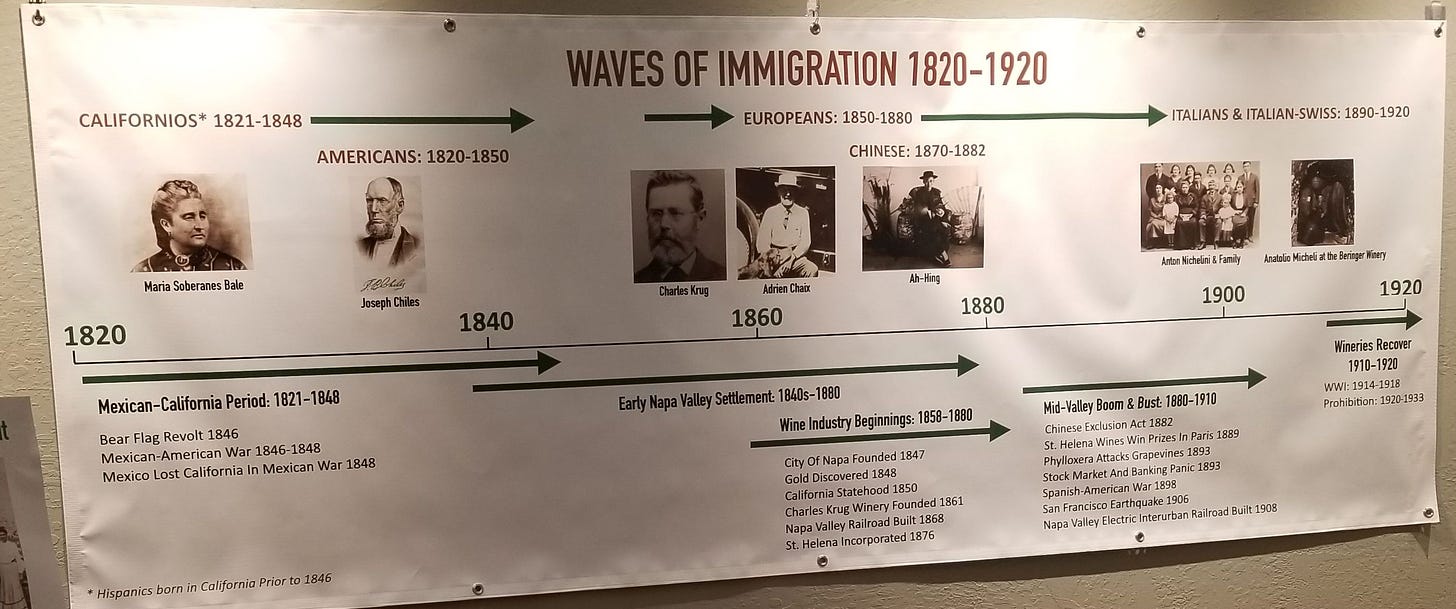

During this period sequential waves of immigrants and migrants arrived, beginning with the migration of Californios (Hispanics born in California before 1846); continuing with Americans from the Midwest and East, Europeans and Chinese; and ending with Italians and Italian-Swiss immigrants. Each exhibit explores the cuisine, businesses, religions, community organizations, leisure activities and tourism brought here from all parts of the world.

In those 100 years, the population of Napa County went from 1,000 to 20,678, according to the exhibits, called “City of Immigrants: An American Story.”

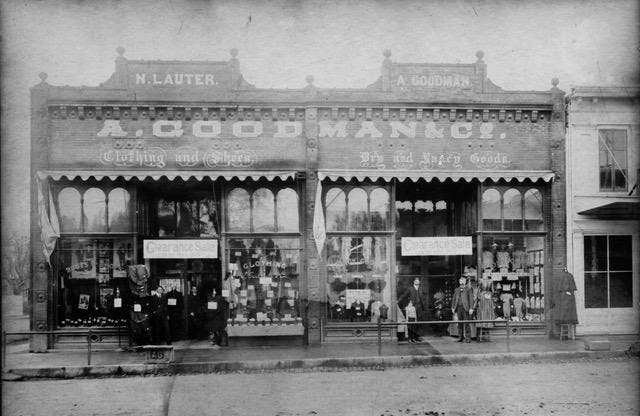

“That’s a pretty steep growth of the population,” said Sheli Smith, executive director of the Napa County Historical Society. “You know the immigrants were from all over, and lots of languages were spoken here. You could stand on one single business block in downtown Napa and hear Spanish, English, German, Chinese, Italian and French being spoken.”

The waves of immigration were not without racism and hatred, especially toward Native Americans, who had lived in the Napa Valley for thousands of years before the white man arrived, and for the Chinese, who worked harder and for less money than white laborers.

From the 1820s through the 1840s, before California became a state, the people here were both naturalized Mexican citizens and Mexican citizens. From 1836 to the time of statehood, roughly 14 years, “the valley still had a fairly significant first-people population as well as a population of Mexican citizens,” Smith said.

“Because of the racism — let’s just call it what it is — the racism and genocide of the immigrants of the early 1850s, we removed all of the first people of the valley. We removed them to the rancherias in California, onto reservations,” she said.

Also in the 1850s, a fairly sizable group of Swiss and German immigrants came to the United States and to the Napa Valley. Their names — Krug, Beringer, Schram — are familiar today because they became the valley’s first winemakers.

“At the same time, I would say a large number of people were coming into the valley from the eastern United States and they’re recognizing the valley’s potential as a resort destination for the waters, the air and the bucolic look of the valley,” Smith said.

Add farmers, including a huge number from Missouri, and “Napa at that point becomes the second largest wheat-producing place in California,” she said.

The waves of immigration over the century created a rich tapestry of ethnicities and cultural blending, and every ethnicity has left its stamp on the Napa Valley, whether or not it is immediately discernible, Smith said.

“When we look around, we see the imprints of immigrants archaeologically and visually as well as in words, names and aesthetics,” she said. “A ‘City of Immigrants’ highlights the impact each group had on the valley, building a more nuanced history that celebrates diversity.” The exhibits continue the theme of telling “stories that were probably not through the lens of who (usually) tells our story.”

Chinese in the Napa Valley

In the 1850s, California and the Napa Valley were growing, and the need for laborers was significant.

“So we had our first big labor shortage,” Smith said. “No labor for the farms, no labor for the vineyards and no labor for mining (quicksilver or mercury), which was beginning to take off.”

The solution was to recruit Chinese men for labor. The wine industry in the Napa Valley from 1870 through 1900 was built predominantly using Chinese immigrant labor. The Chinese population rose from 20 in 1860 to nearly 1,000 in 1880. Not eligible for citizenship, these people were largely confined to living in local Chinatowns, according to information in the St. Helena exhibit.

After building the Transcontinental Railroad, the Chinese came to build the Napa Valley Railroad, reaching St. Helena in 1868. A large amount of gravel was needed for the base of the tracks, according to a June 2011 paper written by Mariam Hansen, research director for the St. Helena Historical Society.

“Although a few Chinese were previously living in Napa, the need for a large labor force to move gravel brought the first large group of Chinese immigrants to the upper Napa Valley,” Hansen writes. “They were housed where they worked, next to the gravel pit, which is now owned by Harold Smith & Sons.”

In January 1872, Overland Monthly reported that “grapes in the northern portion of the state are picked” by Chinese men, who “pick 1,500 pounds a day. They board themselves and are paid $1 a day.” Hansen notes that a large farm-labor force was needed to clear land and plant vines. She notes the men also worked in fields, hopyards and mines.

“Some were household servants, cooks, laundrymen, merchants and clerks,” she says. “They dug the caves at Beringer and Schramsberg. About 100 Chinese worked on the railroad between Napa and St. Helena in 1880.”

Six years later, a crew of 125 Chinese graded Sage Canyon Road.

Jue Joe’s story

One of the Chinese immigrants was Jue Joe, whose great-grandson, Jack Jue Jr., is a family historian and author of the blog “Jue Joe Clan History.”

In January 2023, Jue Jr. interviewed Napa native and author John McCormick at the Native Sons Hall in Napa, hosted by the Napa County Historical Society. The fascinating conversation between the two men can be found on that website. McCormick spoke about his book, “Chinese in Napa Valley: The Forgotten Community that Built Wine Country” and how important the Chinese were in the Napa Valley. McCormick is a fifth-generation Napa Valley resident who grew up and attended schools in the valley.

After his retirement, one of his bucket-list items was getting a master’s degree in history from Harvard. His thesis was on U.S.-China relations. He ran across an article written by Hansen about the Chinese in the Napa Valley, which spurred him to do research on his hometown. As he told Jue Jr., he never learned about this history in school. One of his goals in writing the book was to tell that history. His book was published in 2023 by Arcadia Publishing.

Jue Joe’s experience was typical. In 1874, he emigrated from the Four Districts area of southern China, from which 80% of all Chinese immigrants came. Jue was poor, illiterate and worked as a cabin boy on a steamship from Hong Kong to San Francisco. His great-grandson said he brought 16 pounds of rice for food, and when he arrived in San Francisco, only a quarter-pound remained. He found work through the Chinese Six Companies, which promised him passage back to China at some time in the future on credit.

For a dozen years, Jue was a vineyard farm laborer, spending from sunrise to sunset six-and-a-half days a week clearing land for vineyards, planting vines, harvesting the grapes and pressing them. His rate was $1 a day. At that time, white men were paid $1.50 a day or $1 a day plus room and board. Like most Chinese, Jue sent a portion of his meager wages back to his family in China.

Jue lived in St. Helena’s Chinatown, located on West Charter Oak Avenue at the entrance to town. He left in 1886, when white laborers marched on Chinatown and demanded the Chinese leave, which not everyone did. It was a continuation of the anti-Chinese furor in California — white men thought the Chinese were taking their jobs — that only ended when the Chinese left and the Chinatowns were razed or burned.

Back to China

Jue then worked for a number of years for the Southern Pacific Railroad. He was also a domestic servant for a family in Chatsworth and a potato farmer in the Los Angeles area. Like most Chinese immigrants, he wanted to return to his home in China, which he did in 1902. He married and had two sons. His great-grandson said he would have been glad to stay in China, but he returned to the United States when his brother sold all of Jue’s goods (by now he was a successful merchant) and fled to Paris.

Jue ended up in Los Angeles and became a successful asparagus farmer. His great-grandson said white laborers beat him up several times, and when he was asked why he didn’t fight back, Jue said he couldn’t because the legal system would not allow him to testify against the white people who had assaulted him. From then on, Jue slept with a cleaver and a loaded 44-caliber Colt revolver under his pillow. Jue Jr. said the family still owns the Colt revolver.

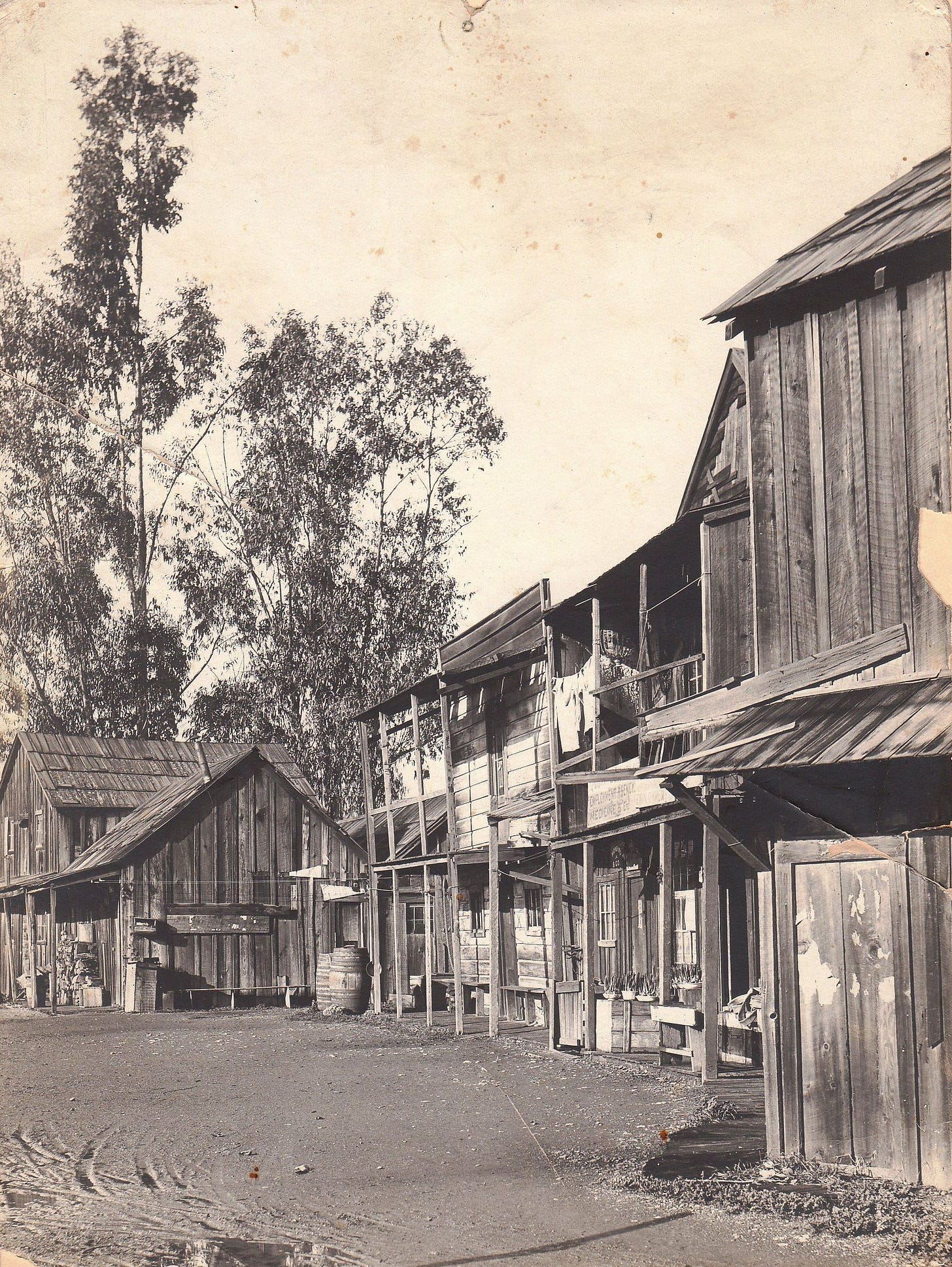

Chinatowns

The Chinese lived in three Chinatowns in the Napa Valley: a large, vibrant one in Napa with its own post office, many stores, a gambling parlor, an opium den and a temple for worship; a smaller one in St. Helena at the southern entrance to town; and the smallest one in Calistoga, near the end of the railroad line, just for those who worked on maintaining the railroad. McCormick estimates the population of Napa’s Chinatown was 2,000; in St. Helena, the population was roughly 400. Most of the housing was made up of rude wooden shacks for the single men who lived there. They rented the shacks as the Chinese were not allowed to own property.

A series of fires from 1884 to 1911 damaged St. Helena’s Chinatown and finally destroyed it completely, according to Hansen’s written history. Napa’s Chinatown was razed in 1927 to make way for a marina, which was never built.

Italian immigrants

“By the time we get to the 1870s, we’re starting to see northern Italian immigrants in the valley,” Smith said, “and then by the 1890s, we see southern Italian immigrants come into the valley.”

Interestingly enough, 2 million Germans immigrated to the United States from 1868 to 1888, which was more than five times the number of Italians, according to Charles L. Sullivan, author of “Napa Wine, A History.” Additionally, during the economic Panic of 1893, there was an oversupply of labor. White workers began flocking to St. Helena in late August to harvest the hops and grapes; a month later, the contract Chinese laborers began to arrive — another point of contention.

Before 1890, most of the vineyard work was done by contract Chinese laborers, but by the 1901-02 season, the Chinese laborers performed a small percentage of vineyard work in the Napa Valley, Sullivan writes. By the 1890s, the original Chinese workers are “aging out” of the workforce. Since Chinese women were not allowed to immigrate to the United States because of the Page Act of 1875, later repealed, there were no second- and third-generation workers to replace the original laborers.

The Page Act of 1875 was the first restrictive federal immigration law in the United States, which effectively prohibited the entry of Chinese women, marking the end of open borders, according to Wikipedia. Seven years later, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act banned immigration by Chinese men, as well. Congress passed the act, which banned Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States for 10 years.

The 1890 immigration from southern Italy was the last big immigration push into the Napa Valley before Prohibition, Smith said. And once Prohibition began in 1920, the growth in the Napa Valley’s agriculture came to a standstill.

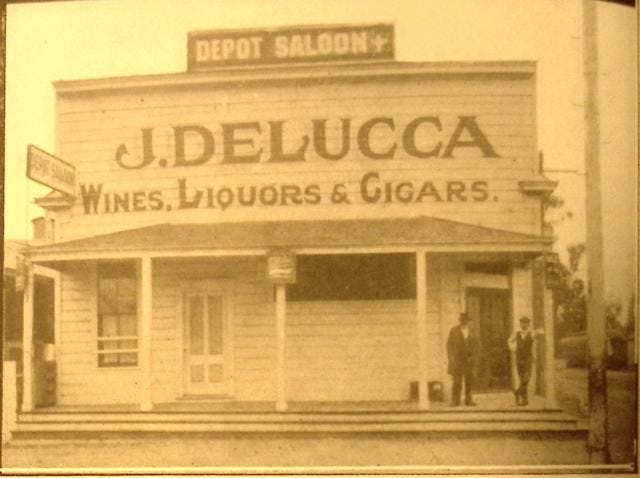

100 historic photos and newspaper ads

The Napa exhibit features more than 100 photographs and an equal number of newspaper advertisements from the collections of both the Napa County Historical Society and the St. Helena Historical Society and four cases of historic objects with the themes of religion, organizations, cuisines, and skills and technology.

Smith said one of the cases is given over to food. Surprisingly, four foods in Napa cross all ethnic lines.

“So, chop suey was eaten by everybody,” Smith said. “Malfattis (Italian spinach ricotta dumplings) have grown to mythic proportions in the Napa Valley, and they’re eaten by everybody.” As were tamales and oysters. “When you went to the bar, you got oysters instead of peanuts.”

The other cases include the kinds of pots that people brought with them and the tools they had for cooking and cuisine.

“We also have some of the things they did for enjoyment,” Smith said, “some of the music that was written here, the Chinese games that were played.”

The Napa exhibit closes March 24. The society’s next exhibit is “Destination Napa: Philosophies of Wellness,” which opens April 5 and continues through Sept. 21. It will be shown in the society’s exhibit hall at 1219 First St. It is free to the public and is open from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., Tuesdays through Thursdays, and 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Fridays and Saturdays. For details visit www.napahistory.org

St. Helena exhibit

The grand opening of the “City of Immigrants” exhibit is Wednesday, March 13, following a 4 p.m. talk by Steve Taplin, who will tell of his family’s journey from England to Vermont and then to St. Helena. Both will be at the St. Helena Historical Society’s Heritage Center, 1255 Oak Ave. in St. Helena.

Also as a part of the exhibit is a free-standing kiosk that tells of 16 local pioneer families and an exhibit of the St. Helena Star, with historic newspapers and photos, including one of its longtime editor Frank Mackinder.

Coordinator and project manager of the exhibit was Kathleen Coelingh, who kept the project on track through design and installation. Others who helped included:

Mariam Hansen, who contributed her vast knowledge of St. Helena history and a collection of vintage photos

Janet Peischel, who designed and created the room’s many posters and timeline

Nancy Caffo, Helen Nelson, Marilyn Coy and Sandra Price, who curated the artifacts

Pam Wieben, who made sure the English language was used properly.

“A City of Immigrants” is available for viewing for the foreseeable future during the Heritage Center’s hours, noon to 4 p.m., the first Saturday of each month.

Napa County population

1850, 1,083

1860, 5,521

1870, 7,163

1880, 13,235 Plus 6,072 in 10 years

1890, 16,411

1900, 16,451

1910, 19,800

1920, 20,678

1930, 22,987

1940, 28,503

1950, 46,603 Plus 18,100

1960, 65,890

1970, 79,140

1980, 99,199 Plus 20,059

1990, 110,765

2000, 124,279 Plus 13,514

2010, 136,484

2020, 138,024

2024, 130,488 (estimated) Minus 7,536 in four years

Answer to average wage question: According to “Journal of Political Economy, v.13, 1905, in Table X, page 363, the average wage in 1872 for unskilled labor in the United States was $1.88 per day. (Source)

For roughly 16 cents a day, subscribing gives you complete access to all our content, while also supporting our mission to provide exceptional local journalism in Napa Valley. Join us and be part of a community that values detailed, local storytelling.

Dave Stoneberg is an editor and journalist who has worked for newspapers in both Lake and Napa counties.

Some years back I took a tour to Chinatown SF and went to a temple. This temple had a large piece of redwood carved in it that had come to SF from the Napa Valley when the Chinese settled here. When they left Napa they took it with them.

What a great article. Thank you.