Sunday E-dition: Locals’ Role in the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt

By Mariam Hansen with Shannon Murray Kuleto

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Californians recognize the grizzly bear as a popular symbol of our state. It even appears on our state flag. Some might also know the symbol’s connection to something called the “Bear Flag Revolt” and the short-lived “California Republic” of the summer of 1846. But did you know that a number of new Napa Valley settlers were at the very heart of this rebellion?

But by 1845 the annual trickle of new Americans coming into California ramped up to a few hundred at once. The local government in Monterey, fearing the Californios would soon be outnumbered, ceased to give these newcomers permission to stay.

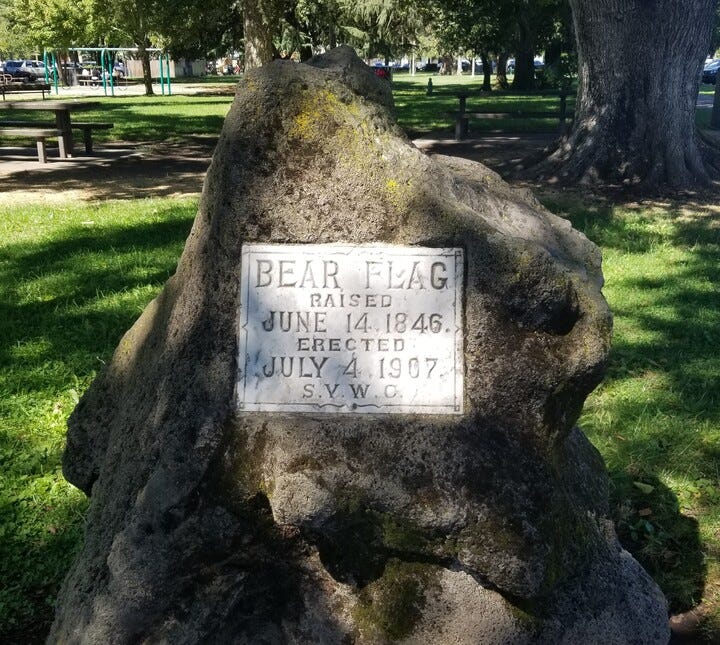

The Bear Flag Revolt saw local settlers declare the short-lived 'California Republic' in the summer of 1846.

Tensions mounted — even more so as news slowly filtered west that the United States and Mexico might go to war at any moment — and the governor ordered Americans out. That command included both the 60-man company of U.S. Army Surveyors under John C. Frémont and the 300 Missourians who had crossed the plains to Sutter’s Fort (Sacramento) in late 1845 in the Grigsby-Ide wagon train. All were to leave the area by the summer of 1846 or be forced out at gunpoint.

Frémont had other ideas, and he took his men to a remote location above modern-day Winters to await the turn of events. The American newcomers, too, had no wish to leave, and they began to see that their only recourse would be outright rebellion. It was an audacious plan, encouraged covertly by Frémont and inspired by Texans who had done something similar in the 1830s. They would take the fort at Sonoma and then hold out in hopes the U.S. government would intervene.

Quite a few of the Grigsby-Ide immigrants had settled in Napa Valley in 1845, wintering with Yount and then finding work in 1846 with Bale building his new grist mill and establishing crops. Their leaders, including John Grigsby of Napa, got fired up after spending some time in Frémont's camp in the Sacramento Valley and resolved to use force to stay here. They started toward Napa Valley, gathering other Anglos along the way. Finally, on June 13, at Bale’s new mill, the group swelled to more than 30 men – about half Napa Valley men – and resolved to attack Sonoma. Among them were several founding citizens of St. Helena, including Calvin Griffith, John York and William Hudson.

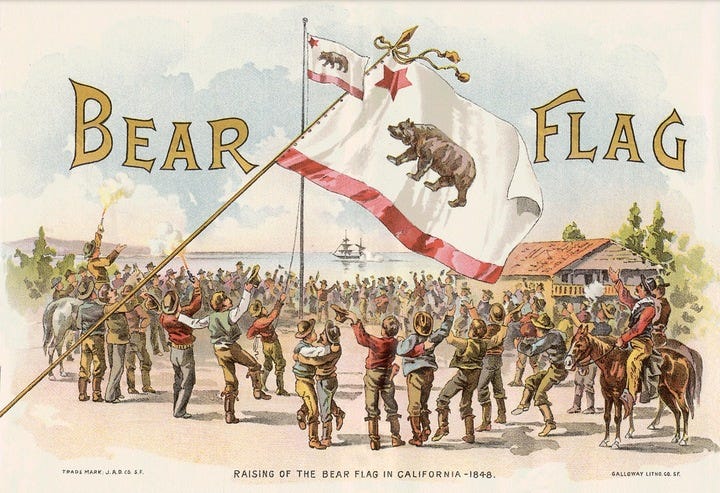

The rough band traveled overnight under cover of darkness. Before dawn on Sunday, June 14, the American insurgents arrived at the pueblo of Sonoma. Meeting no resistance from soldiers, they went next door to Mariano Vallejo's home and pounded on his door. After a few minutes, Vallejo opened the door dressed in his Mexican Army uniform. Communication was not good until American Jacob P. Leese (Vallejo's brother-in-law) was summoned to translate.

Vallejo then invited the leaders into his home to negotiate terms. The insurgents waiting outside sent elected "captains" Grigsby and William Ide inside to speed the proceedings. The effect of Vallejo's hospitality in the form of wine and brandy for the negotiators and someone else's barrel of aguardiente for those outside is debatable. However, when the first agreement was presented to those waiting outside, they refused it. They angrily insisted the Mexicans be arrested and held as hostages. Grigsby refused to remain as leader of the more radicalized group, but Ide took over and gave an impassioned speech that urged the rebels to stay in Sonoma and found a new republic.

Grigsby took charge of the prisoners: Vallejo and his brother, Salvador; Col. Victor Prudon (Mexican Army); and Jacob Leese (married to a Vallejo). The Californios were placed on horseback to be taken to Frémont, along with several insurgents who did not support forming a new republic under these circumstances. That night they camped near Napa. Local Californio Cayetano Juarez sent his brother – disguised as a woman – to ask Vallejo if he wanted to be rescued. Vallejo declined to be released, wanting to avoid any bloodshed and expecting that Frémont would release him on parole. Frémont did not, and the group went on to Sutter’s Fort, where they were held in chains for several months.

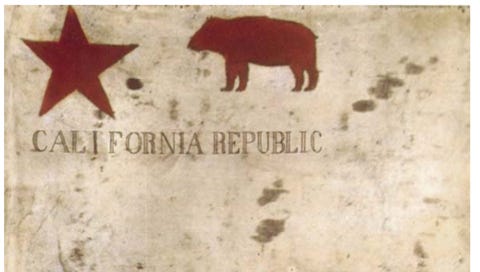

Back in Sonoma, the barracks became headquarters for the remaining 24 rebels. The Napa Valley families all moved to Sonoma for protection, and local American-Californio Chiles was set to protect them from a Mexican counter-attack that never happened. Within a few days the group created their homemade flag – featuring a crudely drawn bear — declaring the “California Republic.” This flag earned the insurgents the nickname Los Osos (The Bears), and the term "Bear Flaggers" stuck. Thus the uprising became known as the Bear Flag Revolt.

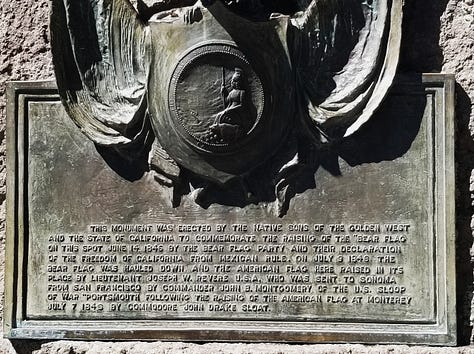

Just three weeks later, after celebrating July 4 in Fort Sonoma, word reached California that the United States and Mexico were at war, and the U.S. Navy took Monterey. When Navy Lt. Joseph Revere (Paul’s grandson) hand-delivered the news and a U.S. flag to the rebels, the Bear Flag came down, the Stars and Stripes went up and the California Republic came to an end.

Most rebels then volunteered for military service with the U.S. Army, many fighting with Frémont to hold California for the Americans until the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War in 1848. In this treaty, Mexico ceded all of their Alta California territories to the United States, including, of course, what we now know as the state of California.

By the next year, in 1849, the Americans, along with pro-American Californios such as Vallejo, who apparently held no lasting grudge for his months of imprisonment, gathered in Monterey’s Colton Hall to hammer out a California Constitution – published in both Spanish and English — to guide its governance. California became the 31st state on Sept. 9, 1850.

Bear Flag exploits were for many years celebrated in our state with pride, parades, statewide holidays and annual reenactments. In recent decades, however, historians more often view this rowdy, armed rebellion of white Americans using extra-legal force to demand land as problematic at best.

In Napa Valley, you can visit the Bale Mill where Los Osos gathered or view the historic plaque by the Napa River in downtown Napa that marks Frémont’s crossing. Many of the participants and their families are buried in either St Helena’s Public Cemetery or in Napa’s Tulocay. In the town of Sonoma, the Plaza boasts a grand statue commemorating the Bear Flaggers, and you can tour the barracks and the place where these men negotiated with — and arrested — Vallejo. The “Paths of History” walking tours in Monterey also offer wonderful insight into these mid-19th-century lives and events.

If today’s story captured your interest, explore these related articles:

Sunday E-dition: Calistoga and Its Library – a Century Long Retrospective

The Historical (And Personal) Significance of Mexican Independence Day

Sunday E-dition: Frank Trozzo’s “IMAGINE THAT!” Art Show is a Fantastical Experience

Ray Ray’s Tacos Adds Spice to St. Helena’s Expanding Food Scene

Sunday E-dition: Mental Health Tips for Caregivers and Students

Sunday E-dition: End-of-Life Planning for Peace in Challenging Times

Sunday E-dition: Retired Judge Brings Real Napa Valley Crimes to Life

Sunday E-dition: WineaPAWlooza Raises $1.1 Million for Animals

Mariam Hansen is research director for the St. Helena Historical Society. Shannon Murray Kuleto is the writer, researcher and editor at Napa Valley Roots.

Levity Corner

Caption contest: Pick your favorite caption or add your own in the comments below.

Possible captions:

"Once, we didn’t need flags to call it home."

"And back then, no one had even invented fences yet!"

"Once upon a time, there were no lines to cross."

"And that, my cubs, is why we never trust beavers with directions."

"The moral? Never argue with a raccoon."

Last week’s contest results

In “Sunday E-dition: Calistoga and Its Library – a Century Long Retrospective,” the winning caption was "Spooky stories are the best when you’ve lived through them!,” with 38% of the votes.

Last Week

In "Under the Hood: Napa Valley Features’ Pursuit of Honest Reporting in a Changing Landscape," Tim Carl reflected on the publication’s mission to provide thoughtful, fact-based journalism that covers all aspects of Napa Valley life, from wine to agriculture, history and beyond. Carl addressed concerns from the wine industry regarding coverage of its challenges, emphasizing the importance of reporting the full truth, including difficult realities. He also highlighted successes and innovations in the region, underscoring Napa Valley Features' commitment to balanced and honest storytelling despite industry pressures.

In "Calistoga and Its Library – a Century Long Retrospective," Rebecca Yerger explored the history of the Calistoga Library, tracing its origins from the late 1800s to its opening in 1924 and its enduring significance. Yerger highlighted the efforts of local women, particularly Mrs. W.L. Blodgett, in establishing the library, as well as the community’s broader historical context, including events like Prohibition, World War II and the rise of Calistoga as a tourist destination. The retrospective also touched on key social and political moments, such as the Ku Klux Klan’s 1924 visit and the economic challenges of the Great Depression.

In "What Would Happen If You Had No Water?" Joy Eldredge and Pat Costello examined the critical role of water infrastructure and the challenges it faces. They highlighted the aging water systems in Napa and nationwide, emphasizing the need for reinvestment to ensure reliable water access. The authors discussed the history and current state of Napa’s water system, which serves 85,000 people, and detailed the risks posed by aging pipelines and treatment facilities. They also encouraged participation in the national "Imagine a Day Without Water" event to raise awareness about water sustainability.

In "Clean up Now for a Great Garden Later," Yvonne Rasmussen discussed essential fall gardening tasks to prepare for winter and ensure a productive spring. Rasmussen advised cleaning up vegetable beds, mulching to prevent disease and planting cover crops to improve soil health. She also highlighted fall pruning tips, explaining which plants benefit from trimming now and which should wait until spring. Rasmussen emphasized the importance of tool care and provided helpful resources for gardeners looking to improve their pruning techniques.

In "The Soil Has a Voice," Dan Berger explored the concept of terroir, emphasizing how the characteristics of the land shape the flavor and personality of wine before human intervention. Berger argued that over-manipulation by winemakers, especially in the pursuit of high scores, can overshadow the soil’s influence and lead to wines that lack regional distinctiveness. He contrasted the nuanced, terroir-driven wines of regions like Russian River Valley with more commercially appealing but less authentic wines. Berger ultimately questioned whether modern wine consumers prioritize terroir or simply value high scores and uniformity.

Next Week

Next week we have more interesting articles from a host of Napa Valley Features contributors. Napa Climate NOW! will join the "Green Wednesday" lineup with climate insights, while the UC Master Gardeners of Napa County offer gardening tips. Dan Berger will discuss how wine appears to be "on the ropes" in Thursday's Wine Chronicles. The Weekender on Friday will feature events and activities across Napa Valley. Eduardo Dingler will explore Napa's downtown scene, Lisa Adams Walter will preview the new Costco opening, and Rebecca Yerger will share local ghost stories. More features and insights will be included as well.

This is the clearest description of the Bear Flag Rebellion I have ever read! It is well done and fair to both sides. As the honorary historian of Tulocay Cemetery, I was fascinated to read of Don Cayetano Juarez's brother's part in offering to help Salvador Vallejo escape. Tulocay Cemetery is located on part of what was Juarez's Rancho Tulucay. I wish this article could become part of the history curriculum for Napa schools.

Two women that I knew years ago had maiden names of Grigsby!!!! Both are gone now