Green Wednesday: The Art of Bonsai and the Ecological Importance of Snakes

By Penny Pawl, U.C. Master Gardeners of Napa County / By Kathleen Scavone, Environmental Contributor

Green Wednesday: Gardening and Ecological Insights

Every Wednesday Napa Valley Features brings you Green Wednesday, featuring articles from environmental voices and the UC Master Gardeners of Napa County. These contributors share research-based horticultural advice and insights on sustainability and climate topics relevant to our region.

Summary of Today’s Stories

"Bonsai Basics: Essential Tips for Growing a Healthy Miniature Tree”: A guide to the essential care and fascinating history of bonsai trees, with practical advice for helping these living art forms thrive outdoors.

"Unlike a painting, a bonsai is never finished." — Penny Pawl

"Snakes: Magnetic and Maligned Creatures”: An exploration of the vital ecological roles of snakes in Napa Valley, offering natural history, safety tips and cultural perspectives on these often misunderstood reptiles.

"By caring for wild critters and their needs we are supporting myriad other animals in the glorious goldmine that is this tremendous planet." — Kathleen Scavone

Bonsai Basics: Essential Tips for Growing a Healthy Miniature Tree

By Penny Pawl, UC Master Gardener of Napa County

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Recently I received an email from a friend asking why a bonsai in her office looked so bad. I had several questions about this plant. First, where did it live? And second, did it have small pebbles glued to the soil surface? I had other questions about the soil and the watering.

My friend told me that she kept the bonsai inside, so I knew at once what was wrong. I suggested that she immediately put it outside in sunlight.

Bonsai are not house plants. I learned this the hard way. As soon as we had furnished our new home, I got a small vase with no hole in the bottom and put a small mugo pine in it. I placed it on my coffee table in the living room. Within a few weeks it was dead. At that point I decided to take lessons and learn more about this ancient art form.

Bonsai are plants living in a pot. Just like plants living in nature, they need sunlight, water and air. My friend brought her plant to a bonsai club meeting recently. As instructed, she had moved it to the sun during the day, and guess what? It was producing new foliage.

Plants rely on photosynthesis — converting sunlight into energy — to make the food necessary for their growth and survival. One byproduct of photosynthesis is oxygen, so the process is also essential to life on our planet.

Houseplants rely on photosynthesis, too, but they get by with much less sunlight. I have a collection of ficus of several types, and I have noticed that the leaves of those that live outside are much smaller and closer together than the ficus I keep inside. Plants try to compensate for a lack of sunlight by increasing their leaf size and growing longer stems. If kept in the shade, they will react similarly to being kept indoors.

At the bonsai club meeting, my friend received a lesson in caring for her plant. It was repotted in a well-draining soil more appropriate for the species. Bonsai sellers sometimes glue pebbles to the soil surface to keep the soil from falling out when the plant is shipped, but the pebbles impede air and water flow. Bonsai soil needs to drain freely.

Bonsai is a Japanese word meaning “plant in pot.” The art form was first practiced in China, where it is known as pinjing. The Japanese adopted it about 1,500 years ago.

Over time, rules emerged to define what bonsai should look like. Ideally, it should resemble a tree in nature. Chinese-style pinjing trees are often forced into shapes with unnatural knots and bends, whereas bonsai should look like a tree in the garden or a tree twisted by wind and storms.

Bonsai was introduced to the United States by Japanese immigrants, some of whom were interned by the United States during World War II. One interned bonsai enthusiast started growing Japanese black pine with bonsai techniques while still in a camp. I knew many of these early bonsai proponents, and they were dedicated to the practice.

American men stationed in Japan after the war also became interested in bonsai. When they returned home, they joined groups to learn more about growing bonsai. Some of the first U.S. bonsai clubs had only Japanese members, but slowly they opened up to include anyone.

John Yoshio Naka is considered the father of American bonsai. Naka was born in Colorado, but it was the custom to send young Japanese American boys back to Japan for a few years to study. That’s where he learned about bonsai. After World War II, Naka settled in Los Angeles and formed the first bonsai club, now the California Bonsai Society.

He used trees native to Southern California, many collected in desert areas, instead of species from Japan. He was a charming man who was much admired for his knowledge and caring. I saw him do several bonsai demonstrations, and I have both of his wonderful books, “Bonsai Techniques I” and “Bonsai Techniques II.”

When the United States celebrated its bicentennial in 1976, Japan sent many bonsai, which became part of the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. Many Americans wanted part of that exhibit to be American bonsai, so an American section was set up. The principal display in that garden is Naka’s creation “Goshin.”

“Goshin” was created using formal Foemina junipers, which represent Naka’s 11 grandchildren. It is the most famous bonsai in the United States, and it is recognized by bonsai groups all over the world.

If you would like to learn more about bonsai, check out the Napa Valley Bonsai Club. The group meets on the second Saturday of each month from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. at the Senior Center in Napa. You are welcome to come, watch and learn more about this ancient art form. And remember that, unlike a painting, a bonsai is never finished.

Events

Workshop: Join UC Master Gardeners of Napa County for a workshop on “Welcoming Pollinators Into Your Garden” on Saturday, June 28, from 10 a.m. to noon, at the University of California Cooperative Extension, 1710 Soscol Ave., Napa. Monarchs and other pollinators are in serious decline. Learn how to create a vital habitat to support the survival of these essential beings. Register here.

Library Talk: UC Master Gardeners of Napa County with Napa Public Library will host a free talk on “A Wonderland of Aloes” on Thursday, July 3, from 7 to 8 p.m. via Zoom. Learn how to repair, upgrade or plan new irrigation for your lawn and garden. Note that the meeting will not allow entry after 7:15 pm. Register to receive the Zoom link.

Help Desk: The Master Gardener Help Desk is available to answer your garden questions on Mondays and Fridays from 10 a.m. until 1 p.m. at the University of California Cooperative Extension Office, 1710 Soscol Ave., Suite 4, Napa. Or send your questions to mastergardeners@countyofnapa.org. Include your name, address, phone number and a brief description of the problem. For best results attach a photo.

—

Penny Pawl is a UC Master Gardener of Napa County.

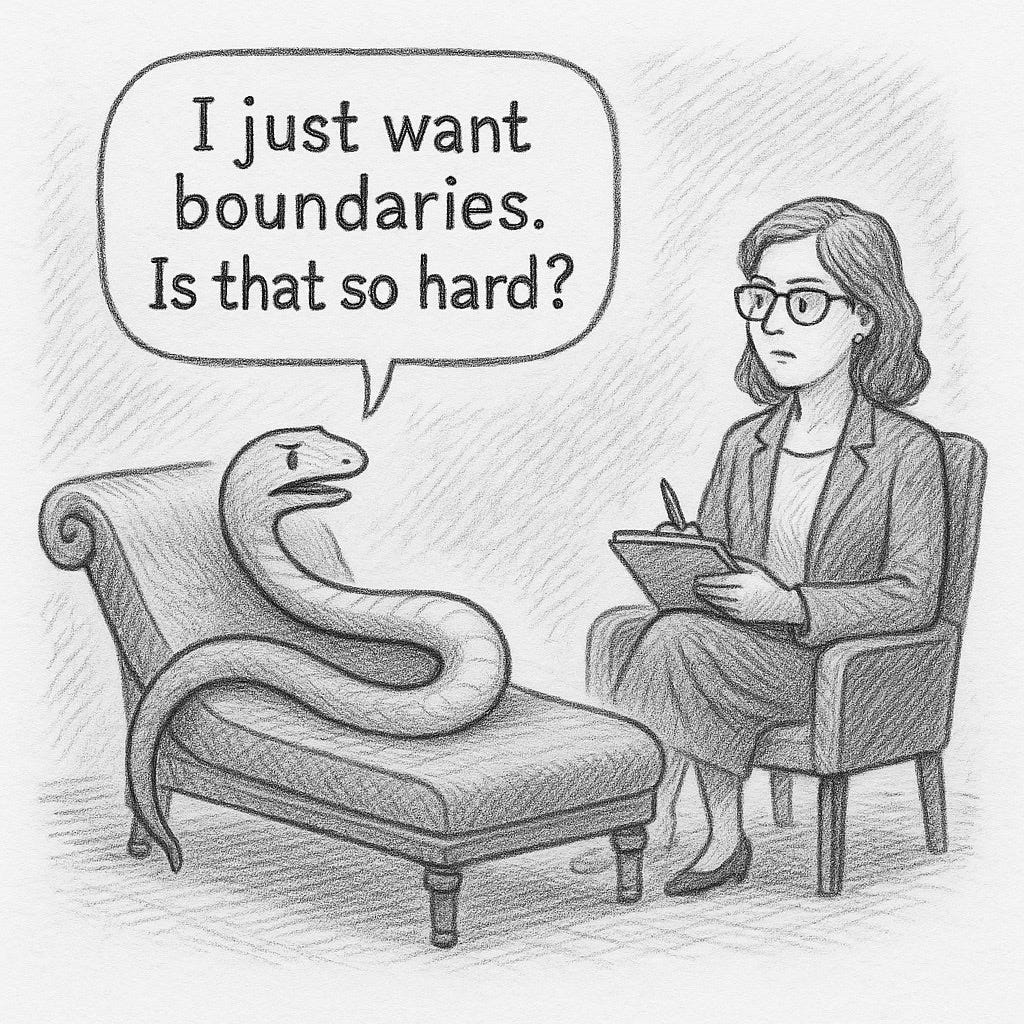

Snakes: Magnetic and Maligned Creatures

By Kathleen Scavone

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. —While on a walk in the lustrous green forest or through the embroidered pattern of slopes and peaks exposed to the sun's lavish light, I'm hyper aware of my surroundings, scanning the trees for critters and birds, scrutinizing sides of the trail as well as what's ahead. I keep an ear out for the unmistakable sound of a western rattlesnake, Crotalus viridis. If I hear one — and knock on wood, I've only heard one once — it means I'm too close, so I give it a wide berth and go waaay around. Although other rattlesnakes I've seen have not shaken their rattles, naturally I took the long way around those, as well, and gave them plenty of room to get away since that is their preference.

Rattlesnakes are both beautiful and deadly, and they are significant players in a healthy ecosystem since they control populations of rodents and other small critters such as invasive ground squirrels, which help keep populations from exploding. Rattlesnakes add to our state's wildlife biodiversity.

Pointers on living in rattlesnake country and preventing snake bites, along with snake photos, can be viewed on the California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page.

The CDFW emphasizes staying alert, wearing boots in brushy areas, inspecting logs and rocks prior to sitting on them, avoiding clutching a stick in the water since rattlesnakes can swim, and not handling rattlers, be they dead or alive, since they are still capable of injecting venom soon after death. The CDFW page also contains information on how to handle a snake bite, with emphasis on calling 911 in an emergency situation and seeking medical attention immediately if bitten.

Gopher snakes Pituophis melanolancus resemble rattlesnakes but are harmless. They will shake their rattle-less tail or hiss in order to scare you off. Gopher snakes dine on eggs, lizards and rodents. It's not easy to tell the difference between a rattlesnake and a gopher snake since you might not always see the rattles on a rattlesnake. You can note the triangle shape of the rattlesnake's head; however, some gopher snakes possess a triangular head, too, so it's best to keep your distance and observe wildlife from afar.

The Lake Berryessa Bureau of Reclamation brochure titled “Snakes of Berryessa” explains that there are around 2,700 species of snakes worldwide. Ten different species are found in the Lake Berryessa vicinity, including gopher snakes, California kingsnake, western rattlesnake, garter snakes and more. Predators of local snakes include eagles, owls, foxes, humans and other snakes.

Snakes both fascinate and repel people. Serpents have been common themes in art and mythology over time. For example, in Sonoma artist Gail Packer's (1945-2008) piece titled “Year of the Snake” she included the naturalistic forms of nature involving plants and animals such as snakes in her highly detailed paintings.

Snakes occur commonly in the mythology of numerous cultures worldwide. Some cultures see snakes’ subject matter as healing, as creation stories or tales of wisdom. The religious story of Adam and Eve has a snake as a protagonist, while the Australian myth of the Rainbow Snake holds that Mother Earth gave birth to all animals. The Chinese have an ancient myth of the woman-headed snake called Nuwa who created humans with clay. Greek mythology holds that Ophion, who is a snake, incubated the primeval egg that was the beginning of creation.

Indigenous cultures in the United States, such as the Hopi, held a snake dance to honor the merger of Snake Youth, which was a Sky Spirit, and Snake Girl, who was an underworld spirit who also restored fertility in nature. In the Pomo myth presented in S.A. Barrett's book “Pomo Myths” there is a story, “The Girl Who Married a Rattlesnake,” in which the snake changes into a handsome fellow who slithers down the center pole of the house to meet the girl and shakes his head to make a scary noise. The story goes on in much detail, and eventually she remains with Rattlesnake and has four children, who naturally became curious as to why the mother is so different from them.

Ringneck snakes, Diadophis punctatus, are a dusky green to black and are found in Napa Valley but are not often seen. They prefer a woodland environment, where they feed upon worms and salamanders. Their moniker comes from the bright orange “necklace” they wear. I was lucky enough to spy a foot-long ringneck one morning at the edge of the woods. What a beauty!

Sharp-tailed snakes, Contia tenuis, are also found in Napa's forests or grasslands. These are burrowing snakes that prefer moist soil. I came across one when I was raking some leaves by Bradford Creek near the Napa border. I left his moist leaf pile intact and gently placed him back in his hideout. These snakes dine on slugs and salamanders. He should be pretty happy there with all of the banana slugs I've seen around.

Western aquatic garter snakes, Thamnophis couchi, as their name implies, love the water, where they can hunt for salamanders, fish and crustaceans. Their trick is to flick their tongue above the water to imitate an insect in order to lure it to their waiting jaws.

Gopher snakes, as well as rattlesnakes, can be arboreal, or tree-climbing, to search for prey such as squirrels or birds or to seek the warmth of the sun. They have also been known to tree-climb in order to dodge predators or weather.

The continuous loss of habitat for reptiles and other non-human life in California due to human encroachment means that for the plight of a balanced food web we can appreciate slithery snakes and their interconnecting habitat. At the very least I know that I will continue to respect their natural places and avoid disturbing logs, leaf piles or rocks to avoid contact. In my garden I will steer clear of leaving netting around, since one year I used netting to keep the birds from eating my seedlings but realized too late that both a snake and a lizard that were investigating the netting sadly became caught up and expired before I could rescue them.

By caring for wild critters and their needs we are supporting myriad other animals in the glorious goldmine that is this tremendous planet. Aristotle, the ancient Greek polymath, said, "In all things of nature there is something of the marvelous."

--

Kathleen Scavone, M.A., retired educator, is a potter, freelance writer and author of “Anderson Marsh State Historic Park: A Walking History, Prehistory, Flora and Fauna Tour of a California State Park,” "People of the Water" and “Native Americans of Lake County.” She loves hiking, travel, photography and creating her single panel cartoon, “Rupert.”

I really enjoyed this article

When we permit conversion of a natural landscape ( woodland, chaparral, riparian, grasslands, coniferous forest to vineyard, we destroy habit for hundreds of plant and animal species. How we have come to allow ministerial destruction by planning staff is incomprehensible.