NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Will Ashford, an artist and designer whose work spans various mediums and venues from watercolors to conceptual installations that have gained global recognition, is no stranger to overcoming challenges.

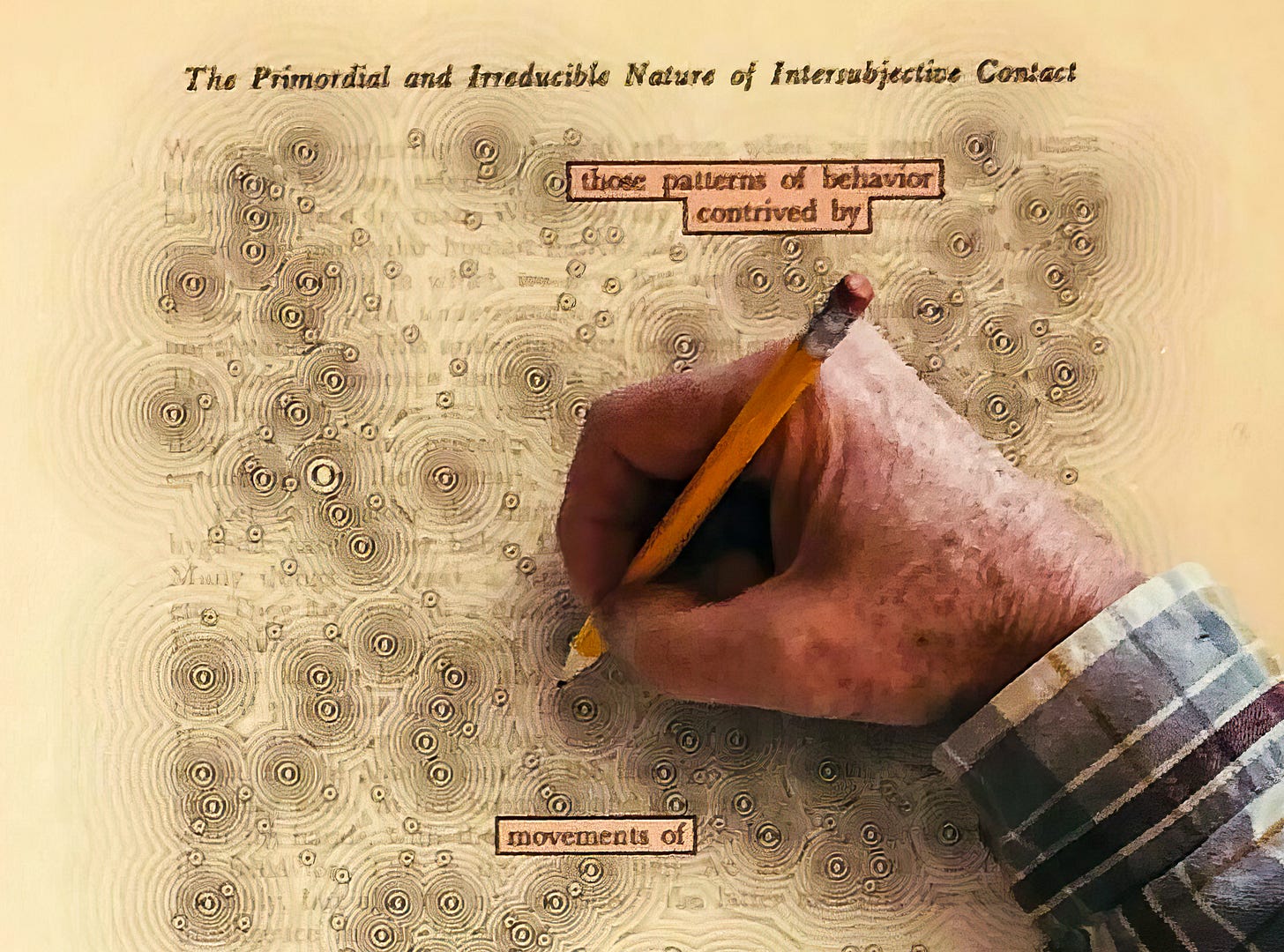

Ashford, knowing that someone without dyslexia can't truly understand it, has been finding ways to visually portray what dyslexia “feels like.”

Now, for the first time since the 2017 Tubbs Fire destroyed his home and much of his work, Ashford is displaying a large collection of new paintings and prints in “Wordscapes,” a solo exhibit at Sofie Contemporary Arts in Calistoga.

His inspiration for creating this series was to further an understanding of dyslexia, a learning disorder that hinders reading due to problems with decoding speech sounds and learning how they relate to letters and words.

Ashford’s own dyslexia, which negatively impacted his self-image during his school years and wasn't diagnosed until adulthood, fuels his motivation for this work.

"Dyslexia was not commonly known or understood in the first half of the 20th century," Ashford said.

He learned about dyslexia in the early 1960s from a TV documentary, realizing his perception that “text was floating or transforming on the page” might be linked to it.

“I’d become adept at hiding that I understood text in a different, often scrambled way,” he said. “Discovering dyslexia was a revelation. I was relieved to know I wasn’t lacking intelligence but simply saw differently. My reading, writing and spelling difficulties were due to the condition, which I began investigating.”

Ashford, knowing that someone without dyslexia can't truly understand it, has been finding ways to visually portray what dyslexia “feels like.”

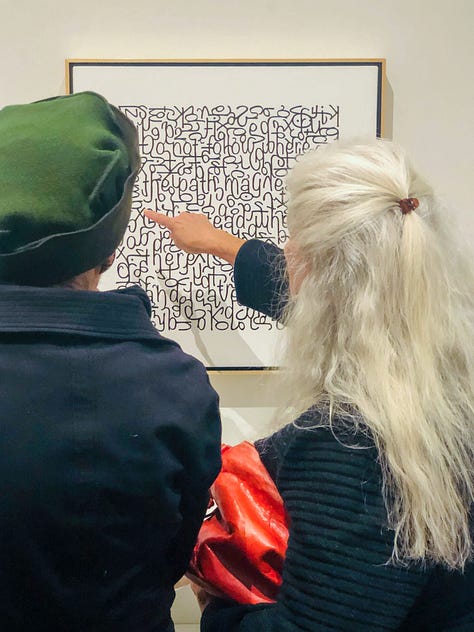

The large, pristine black-and-white canvases in the “Wordscape” series use various fonts to create a “dance” of letters, each piece moving to its own rhythm, like jazz or a waltz.

“I like making fonts look as if they’re dancing, not just standing as words,” he said.

The fonts in some compositions tumble or merge, while others are carefully controlled, all painted with precision and attention to craftsmanship.

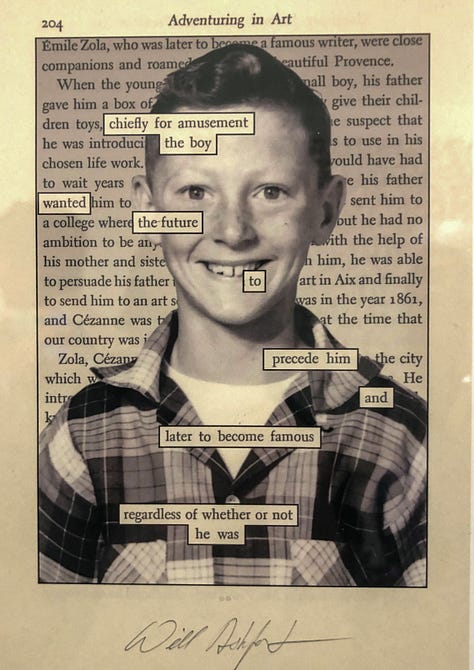

Smaller framed prints of “pages” from altered art books show selected words forming new messages and camouflaged with visual imagery.

“Will had many of these ‘pages’ we planned to show years ago, lost in the Tubbs Fire, so we're showing about a dozen he's created since,” said Jan Sofie, the gallery’s director.

Ashford’s art has been displayed here and at other galleries, but it was a conceptual piece too large for a gallery that brought him worldwide attention.

In 1979, Ashford re-created Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” on a hillside off Interstate 680 and Stone Valley Road, using 800 pounds of fertilizer on wild grasses. The fertilized grass grew darker and longer, revealing “Mona Lisa” to commuters on I-680.

“'Mona Lisa' was for commuters,” Ashford said. “People recognized it and heard about it on the radio. Traffic helicopters noticed it, and the California Highway Patrol used it as a reference point.”

Life magazine, National Enquirer and the February 1980 issue of London Times Magazine publicized the hillside “Mona Lisa.”

In 1983, he used the same hillside for Andy Warhol’s “Marilyn Monroe,” with yellow flowers from scattered seeds creating Marilyn’s hair. That one was featured in the Swiss magazine Die Weltwoche.

In 1986, he created a sunburst geoglyph on a 21-acre land parcel, which resulted in a story in Diablo Country. He has done other innovative design projects and large-scale installations in the United States, including for Red Bull. Words have been prominent in much of his conceptual art.

Ashford has used the words “wet” and “dirt” in his art, and before creating the “Mona Lisa,” he grew “green” and “landscape” on the hillside.

His fascination with words in art stems from his dyslexia. Though it caused school struggles, it later offered valuable compensations.

“I still can’t spell,” he said, laughing, “but I have a vast visual memory.”

The list of famous dyslexic artists, starting with Leonardo da Vinci, is long. Ashford believes many artists are dyslexic, which benefits their art.

If today’s story captured your interest, explore these related articles:

Valley Players champion mature women and their untold stories

Three Napa Valley women champion arts and community projects

Rosemarie Kempton is an author living in Napa County