Support Napa Valley Features – Become a Paid Subscriber Today

If you’re reading this, you care about independent, locally owned, ad-free journalism — reporting that puts our region’s stories first, not corporate interests or clickbait.

As local newsrooms are increasingly bought by billionaires, scaled back or absorbed into media conglomerates, communities lose original reporting and are left with more syndicated content. Your support keeps quality regional journalism alive.

Join a community that values in-depth, independent reporting. Become a paid subscriber today — and if you already are, thank you. Help us grow by liking, commenting and sharing our work.

Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: Varietal Precision — Reds

By Dan Berger

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — I really can’t blame people who pick up a bottle of wine, pull the cork, pour a splash and immediately want to declare what they perceive the quality to be — good or unscrupulous. (People who sell wine can be disrespectful of products that compete with those they are selling.)

Wine is for enjoyment and to help our food taste better, and no one really wants to open a bottle of wine and instantly become a technocrat. Still, as we indicated last week when we spoke about white wines, the more we get to know about the actual aromatics and potential tastes of specific wines, the more we can appreciate the subtle differences between them and wines from different grape varieties.

White wines tend to be a little bit easier to identify aromatically than red wines. Since most reds are made in similar ways, trying to parse them can be relatively dicey. Also, many people do not know what to look for when they pick up a red wine. Since those who score wines by numerical rankings have created a single dimension for quality, anything that is relatively dense is automatically better than anything that is delicate. And varietal aromas are almost never considered.

This week we look more deeply at popular grape varieties that make some of the most interesting red wines. Many red wines were left out intentionally (i.e., tempranillo, malbec, carignane, tannat) because they are not particularly distinctive and they tend to be rather generic and/or too often are made to be non-distinctive. And others for which I happen to have a personal affinity were left out because they tend to be too obscure — blaufrankisch, Nero d’Avola, cinsault, dolcetto, primitivo, lagrein, sagrantino, zweigelt).

Cabernet Sauvignon: This is one of the most complicated and controversial wine grapes partially because it delivers so many different characteristics in so many different areas of the world. Its primary aromatic is herbal, similar to dried herbs. However, the grape has some of the most alluring and fascinating fruit elements that include black cherry, cassis and fresh plum, earth, tar and pipe tobacco. Some might say cab can be too herbaceous. When grown in very cool or windy regions, it can deliver an aromatic that is more akin to green pepper. Most of today’s cabernet buyers consider this aroma to be off-putting. (Technically, this aroma is called pyrazine.) But today far too many Americans have been brainwashed to believe that any herbaceouness, even just trace amounts, is a negative trait. So most producers make a strong effort to destroy any trace of herbs.

As a result, we are left with far too many cabernets that have no cabernet-ness at all. This is one of the saddest situations that cabernet has faced in its history, and it’s one about which I am writing a book. However, because cabernet is so wildly successful throughout the world, most notably in France’s Bordeaux region, it is seen in a huge range of styles.

Red Bordeaux is still the world leader in terms of cabernet and cab blends (with merlot, cabernet Franc and other cousin varieties added). But because of its rigid tannins, young versions can be particularly difficult to drink, so they are best when they are aged at least a little bit, which changes their aromatics in so many different ways that it is difficult to describe the wines.

Cabernet also can be infected with some spoilage elements that can exacerbate their aromas and aftertastes. And those who decry the herbal elements in cabernet might very well be unaware that when these “green” cabernets are aged for a decade or more, they become fascinatingly complex as the herbs begin to decline. Cabernet is usually aged in oak barrels, and the result, especially when those barrels are new, can be a wine with so much oak flavoring that it is considered by newcomers to wine to be a powerful statement. But purists usually prefer cabs that have less oak and more fruit.

Cabernet Franc: There is a fascinating kindship between cabernet sauvignon and its father, cabernet Franc. The two grapes offer similar aromatics with each delivering some of the same dried-herb components. But CS is more wildly teenager-ish in its aggressive herbalness, rustic-ness and higher tannins. Cabernet Franc usually has a bit more graceful fruit, less tannin and requires less time in the bottle to deliver mature flavors. Its supporters suggest that it can be more interesting than cabernet sauvignon because it is easier to understand when it is young, and it does not take as long in an aging cellar to develop secondary characteristics that are fascinating.

Cabernet Franc is best grown in volcanic or high-altitude soils, and it ripens about two weeks earlier than cabernet sauvignon – which means it can avoid late-season heat waves. Cabernet Franc has become so popular in the Napa Valley that average grape prices for it in 2023 and 2024 were higher than for cab sauv. Cabernet Franc can produce such delightful aromatics that it can make rosé wines that have real personality. Also, the variety produces some excellent lower-alcohol red wines in numerous East Coast wineries. It grows well in New York, Virginia, and other locations where it rarely gives dark-colored wine, but its aromatics develop beautifully within four to six years in the bottle.

Merlot: Not unlike cabernet sauvignon, this earlier-harvested grape, which comes from the same family as CS, is slightly herbal, but its most charming primary aroma is the lovely fruit component of fresh berries and plums often delivered alongside trace amounts of green tea, dried herbs and tree-ripened olives. Its greatest attribute as a blending grape for cabernet assemblages is that it reduces the tannin component of any cab blend. On its own, merlot produces a red wine with more flesh and less bitterness/astringency than cabernet.

And it can age beautifully, albeit for typically less time than a cabernet. It prefers to be grown in clay soils and in cooler areas. A complete misunderstanding of the variety two decades ago led a character in the popular film “Sideways” to utter disrespectful remarks about this gorgeous grape, leading to a long and protracted distaste for it by many Americans. But it is vital in France’s Bordeaux and should be far more respected here than it is. Fortunately, it is making a strong resurgence in popularity.

Pinot Noir: The seductive aromas of pinot noir from Oregon and California diverge from those of the great regions of Burgundy in France. And those are significantly different from moderately priced versions of PNs grown elsewhere. (New Zealand is making enormous strides in some regions to produce world-class pinot noirs.) American versions often deliver somewhat simplistic fruit; great red Burgundies usually deliver more complexity, but the best are ludicrously expensive. Trying to delineate each of them in so small a space is impossible. In the last 30 years or so, Oregon and California have made huge strides toward making PNs with “Burgundian-ness.” Burgundy fanciers are universally disdainful of almost every American version, calling them imposters. To say that California’s best PNs deliver red cherry, raspberry and strawberry components in their aromas would be valid, region to region, but far too simplistic. British wine lovers typically adore excellent Burgundies in spite of their excessive prices, and in discussing them, they often refer to the aroma of beets in some of the best wines.

Numerous versions can also deliver subtle elements that come from fresh tomatoes or tree bark. André Tchelistcheff, America’s greatest winemaker, said making great pinot in California is as difficult as anything any winemaker faces, and he emphasized that it must be made more in the vineyard than in the winery. He described a great pinot noir as having an aroma of a faded rose. California has several different regions that make exemplary PNs, and styles can vary – from the graceful (Anderson Valley in Mendocino County); to the rustic (the distinctive wines of Santa Cruz Mountains); to the rich, fragrant and long-lived (Russian River Valley); to the startlingly interesting versions from Carneros and Santa Barbara County.

One thing is certain: To get a great California or Oregon pinot noir, prepare to spend $60 to $80 (or more). To get a great Burgundy, prepare to forgo retirement. One major difference between great Burgundy and PN grown anywhere else is that the former will age for decades. California and Oregon PNs usually are best at 10 to 15 years.

Zinfandel: Raspberries and strawberries and a fascinating spice component once were the dominant aroma characteristic in excellent zinfandels. The best were produced in both Sonoma County and Napa Valley, with many excellent versions coming from Mendocino County, the Sierra Foothills, Lodi and pockets in the state’s Central Coast like Paso Robles. Many decades ago, classic zinfandel was seen as a wine that could produce everything from white, pink and graceful Beaujolais all the way to dark and heavy powerful reds and even dessert wines similar to port.

Over time, however, many amateur wine drinkers began to seek zins with far more intensity. One result was unfortunate: Alcohols increased from about 13% to 14%, then 15%, then 16%. And a few were even higher. This became possible because grapes were picked far too late. Raisins replaced fresh fruit, and we began to lose zin distinctiveness.

Thirty years ago, zinfandel popularity was at an all-time high, but so were alcohol levels. In the last decade, however, zin sales began to decline precipitously. The raspberry/strawberry/spice elements had been largely replaced by overripe aromatics that had far less interest than in previous years.

I know many older zin lovers who championed its more charming self in the 1970s and today have completely turned their backs on the grape. A recent discovery shows that a grape variety from Croatia called tribidrag is genetically identical to zinfandel and produces a fascinating, pepper-scented red wine. I personally believe that primitivo, which the U.S. government permits to be called zinfandel, has nothing to do with zin.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

Syrah (Shiraz in Australia): This dark grape is a producer of some of the world’s most fascinating and long-lived red wines. But its history in the United States seems to be tarnished by some poor decisions on how it grows and how it is harvested. The variety often delivers exotic plums, black cherries and a rustic element that is unique to the grape, notably from warmer regions. In colder climates, however, it can deliver a distinctive, dramatic black pepper aroma (rotundone) that allows the variety to take on additional complexity with aging in a cool cellar. Wherever it grows, it can show much complexity of earth, tar and forest floor that, when combined with substantial tannins, makes wines that demand a lot of aging.

Syrah produces some of the finest and longest-lived red wines in France’s northern Rhône Valley (such as Hermitage and Côte-Rôtie) as well as in Australia’s Barossa Valley. The finest New-World examples come from Australia’s northern Victoria and two regions in New Zealand, Hawke’s Bay and Martinborough. In the southern Rhône Valley, syrah often is blended with up to a dozen other red wine grapes to produce countrified blends that include syrah and grenache. Designations are Côtes du Rhône and Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

Petite Sirah: This underrated dark grape with high levels of concentrated but somewhat generic fruit flavors has been identified as durif from the south of France, where it is a minor grape used primarily for blending. However, in California’s extremely sunny and warm climate, petite sirah performs extremely well. In the 1950s and 1960s, before cabernet became a big deal, this was one of the most popular red varieties growing in the Napa Valley. It produces wines with a density of slightly simplistic fruit such as plums and ripe black cherries with traces of indeterminate dried herbs. The wines tend to be extremely tannic when young, and many of them can develop beautifully with a lot of time in the bottle.

High tannins help protect it from oxidation, so it is often used to bolster red wine blends because it produces wines with a lot of color and longevity. Red wine blends tend to be more stable with petite sirah added. Curiously, petite sirah is grown in several vineyards in Australia’s Rutherglen, which is much better known for its concentrated dark Muscat dessert wines. (In Rutherglen, it is called durif.) As cabernet became popular in the Napa Valley in the 1990s, several hundred acres of petite sirah were converted to cabernet. But petite sirah is still a popular variety in Sonoma County as well as in Mendocino, where it can produce superb dark red wines.

Grenache: Aromas of cranberries and/or fresh pomegranates once were dominant in this lovely red grape that is difficult to grow. It wants to produce so much fruit that growers must be ruthless in how the vine is treated, cutting back on production significantly. This charming grape adds measurably to blends that include syrah. But caution must be used: If Grenache’s alcohols rise too high, one consequence might well be a loss of distinctive automatics. Australian grenaches can be dramatically interesting with its pomegranate aromatics and relative density. The grape also delivers a personality-driven red wine in many areas of Spain, where it is called garnacha.

A little like “spicy” zinfandel, grenache’s popularity has shrunk in the last few years because so many producers were emphasizing intensity and slightly overripe flavors. As alcohols rose above 15%, those who appreciated the balance and charm of this grape lost interest in it. Not unlike syrah, grenache grown in cooler regions or during a cold vintage can produce red wines with a black-pepper characteristic, which can be fascinating and long-lived. But only if the grape is harvested early enough so that its alcohol is not excessively high. In 2002, one of the coolest vintages on record in Australia, Pirramimma Wines in McLaren Vale made a grenache that had loads of black pepper in its aroma. More than two decades later, that wine is still alive.

Nebbiolo: One of the world’s greatest grapes is this unique, lighter-colored cultivar that grows properly in very few places in the world. Its native fatherland is cold northern Italy, in a district called Piemonte (Piedmont), where it produces an amazingly long-lived and concentrated red wine called barolo. However, it has never proven to be particularly classic when it is grown in very warm climates. I suspect that the acid levels tend to be too low unless the region is much colder. As a young wine in Italy, historic examples were always extremely tannic and often did not show particularly distinctive fruit. For that reason, the best examples of barolo usually were not released until they were five to seven years old.

A book written decades ago about barolo and (usually lower priced) nebbiolo was titled, “Tar and Roses,” which purportedly referred to the aroma of barolo. However, there is a faint rustic characteristic that seems to pervade the wine alongside a fruit component that is not particularly dense. In fact, a great example of quality barolo is rarely dark in color. The grape name is taken from the Italian word for fog, nebbia, and one of its proclivities is that it seems to grow best in colder climates, particularly where fog shrouds the vines. Where there is lots of sun, the grape itself grows fine, but though the resulting wine can be attractive, it rarely carries the properties of great barolos. A few wineries in California have made attractive nebbiolos, but few developed like barolo.

I have tasted 50-year-old barolos that were amazingly scented and still loaded with fruit and have read about even older barolos that were superb. A winemaker friend and I discovered a phenomenal barolo-type wine three years ago. It was made by Wilridge Winery in the Naches Heights appellation, a suburb of Yakima, Washington. Its nebbiolo and two other red wines from Italian grapes are exemplary.

Barbera: “The people’s grape” of northern Italy, barbera grows brilliantly in Piemonte and once was regularly blended into nebbiolo-based wines to help darken barolos that were a bit too light in color. Blackberry-ish barbera is sort of like a counterpoint to nebbiolo because it has lower tannins, so it’s nowhere near as astringent as its big brother. But it has higher acidity than nebbiolo. Its aroma can be plum-y and display broad, somewhat simple fruit. The grape’s high acidity also gives it a faint citrusy note.

Lighter barberas from Asti and richer, denser versions from Alba both are excellent to accompany red-sauced pastas. In the last 20 years or so, the variety has gained wide popularity. Today it is grown widely outside of Italy, most notably in California’s Sierra foothills. It’s a star in Amador County, where it produces excellent examples of relatively rich, dark red wines that benefit from four to 10 additional years in the bottle. Amador County hosts a Barbera Festival that usually sells out. This year the event ($55 per person) will be held on Aug. 16 (https://amadorwine.com/barbera-festival/) . The best barberas I ever tasted were from Giacomo Bologna, who pioneered the production of exceptional single-vineyard barberas in the tiny Piemontese town of Rochetta Tanaro.

Sangiovese: One of the world’s most widely distributed red wines is Chianti, an Italian wine that emanates from Tuscany and is made primarily of the high-acid grape, lighter-styled sangiovese. Chianti can range from utterly simple, tasty tart red wines aimed at unassuming spaghetti-and-meatball dishes all the way to richer, expensive examples that sell for exalted prices. Even though Riserva Chiantis can be relatively concentrated, they last only about 25 years in the Bottle. (Barolo can age far longer.)

The best Italian sangioveses usually come from the heartland district called Chianti Classico; Chianti Ruffina also produces high-quality wines. Many pricey Chiantis and most Riserva Chiantis contain some cabernet, which can alter the Chianti personality. They are more broadly appealing to American consumers, although they are not as authentic as Tuscany normally produces. To solve that issue, a new category of Chianti called Grand Selezione requires Chiantis with that designation to be 100% sangiovese, no blending permitted.

Sangiovese was widely planted throughout northern California starting in the 1980s, but for various reasons it never caught on with the public. Many of the wines turned out to be unlike Chianti. They were quite a bit heavier, and the style in which they were made was not particularly exciting to American consumers. One of the largest sangiovese plantings, at Atlas Peak in Napa’s hills, eventually was converted mainly to cabernet.

Gamay Noir a jus Blanc: Usually called simply gamay, this is the charming grape that produces all Beaujolais, from the simplest to the most complex (called Cru Beaujolais). The aroma of the wines can be interestingly fruity with a faint note of cherry jam. Wines with the designation Cru Beaujolais have far more complexity, with hints of black pepper (especially in cooler climes) and a similarity to medium-weight pinot noirs. Gamay rarely develops with a lot of age; a decade is usually plenty; most are best at three to four years. A better wine than straight Beaujolais is called Beaujolais Villages.

When the best cru wines are produced to reflect the soils in which they are grown, they can be enchantingly adaptable to a wide variety of lighter foods and deliver interesting characteristics. There are 10 designated crus. Several are distinctive enough to be identified by experts. Restaurant wine lists assembled by intelligent buyers once routinely carried at least one Beaujolais because it was almost always a good value, a reasonably priced red alternative for those seeking a simple wine to go with simpler dishes. Today, Beaujolais Villages and Cru Beaujolais remain staples on many East Coast restaurant wine lists, but it is rare to find it on the West Coast.

Although most of the popular red wine grapes can be made with techniques to allow the wines to develop additional complexities with some bottle age, most of today’s wine buyers seem particularly smitten with the up-front fruit that young wines usually deliver. As a result, some aging of today’s red wines is nowhere near as popular as it was 30 years ago.

Next week we will take a look at how standard table wines should be handled for maximum enjoyment. We will also take an excursion into some extremely fascinating wines that are worth investigating, such as Champagne, port, sherry and other dessert wines.

Wine Discovery

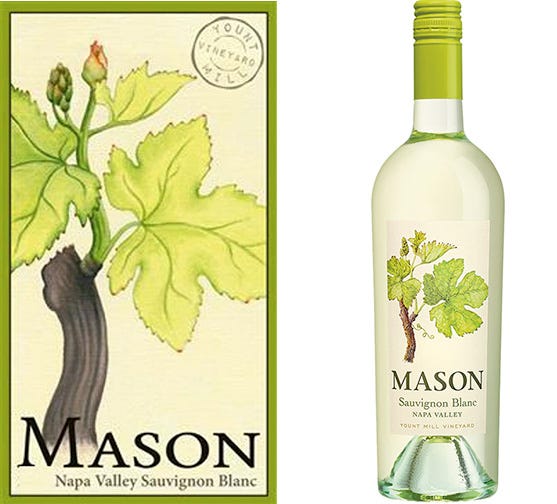

2023 Mason Cellars Sauvignon Blanc, Napa Valley ($18.95): Randy Mason has been making excellent sauvignon blancs since 1993, and a decade before that was making excellent wines from an area of south of Yountville known as Yount Mill. This wine is a product of his experience. It offers lovely pink grapefruit and herbal tea aromas, a relatively rich entry and good acidity. It probably will be better in two years, although most buyers will not want to wait. It’s very tasty right now, especially because it avoids being as sweet as some SBs are these days.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is C: "Fill level of a wine bottle"

The ullage level of a wine bottle is sometimes described as the "fill level." This describes the space between the wine and the bottom of the cork. During the bottling process, most wineries strive to have an initial ullage level of between 0.2–0.4 inches (5–10mm). As a cork is not a completely airtight sealant, some wine is lost through the process of evaporation and diffusion. As a wine ages in the bottle, the amount of ullage will continue to increase.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

—

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.