Dan Berger's Wine Chronicles: A Taste of the Soil

Why balance, place and subtlety are losing ground in America’s obsession with big red wines

We Need Your Help

If you’re reading this, you care about independent, locally owned, ad-free storytelling — reporting that puts our region’s stories first, not corporate interests or clickbait.

Join a community that values in-depth, independent reporting. Become a paid subscriber today — and if you already are, thank you. Help us grow by liking, commenting and sharing our work.

Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: A Taste of the Soil

By Dan Berger

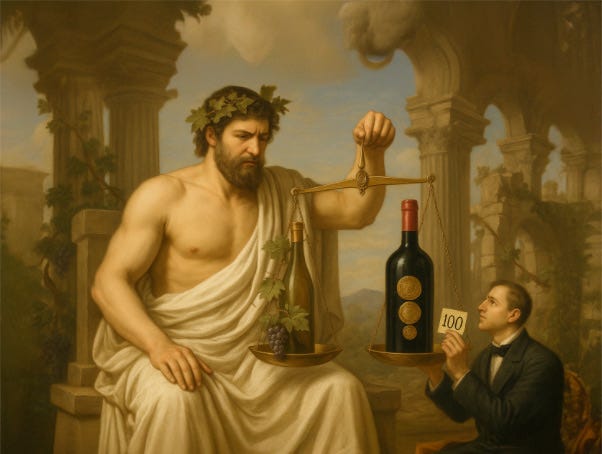

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — People who purchase wines that they anticipate will turn out to be great in a few years might do so primarily because of someone else’s idea about how many points it deserves. Or a buyer might use a simpler criterion – the historical image of the winery and what that brand represents. And there are other considerations that enter the picture, as well.

For most people who are considering an expensive red wine, one they assume (because of its high price) will be great, the final decision before plunking down a wad of cash might rely on other assumptions that could include the opinion of a trusted or persuasive wine merchant or even the comments of a pushy salesperson who exudes expertise but is really a pompous jerk with an enormous ego.

“[Many modern wine consumers] do not want individuality; they want intensity.”

Rarely, however, is a buying decision based solely on the purchaser’s taste. Few people buy one bottle of a target wine, try it and spend days deciding whether to buy more.

Such a process entails far too much calculation. And it is unemotional — and most expensive wine purchases tend to be more passionate than that. Any approach that includes careful analysis almost always is far too complex for the average wine collector. “I really want that” almost always outperforms “Academically, it’s nicely balanced.”

And with California red wine, rarely does the sub-region from which it comes enter into the decision. Although the location of the vineyard means a lot in Europe, where fine wine originated, most American buyers have no interest in such esoterica.

Here is a case in point that comes from 2004: A Napa Valley merlot that was extremely highly regarded by a major wine magazine was inserted into a blind tasting of 10 merlots a few weeks after the magazine implied that on a scale of hedonism the wine exceeded Nirvana.

Challenge your vocabulary with this week’s mystery word. Submit your answer in the poll, and check the bottom of the page for the correct answer.

One person in a group of seven judges knew this wine was in the tasting and was thrilled to have gotten a bottle for the event. Of the six other judges at the table, four said the wine was OK though it had a few flaws that disqualified it from being more than middling in the group of 10. The other two other judges (including me) found the wine to be utterly blah – not one of the greatest of all time. Had anyone served it to me, I would have opted for a glass of water.

The coordinator of the event was frustrated that the score it received was poor, especially since this bottle was so highly praised and had risen in price to “ludicrously expensive” and was now impossible to get.

One taster, an excellent Sonoma winemaker, said the merlot wasn’t varietally correct.

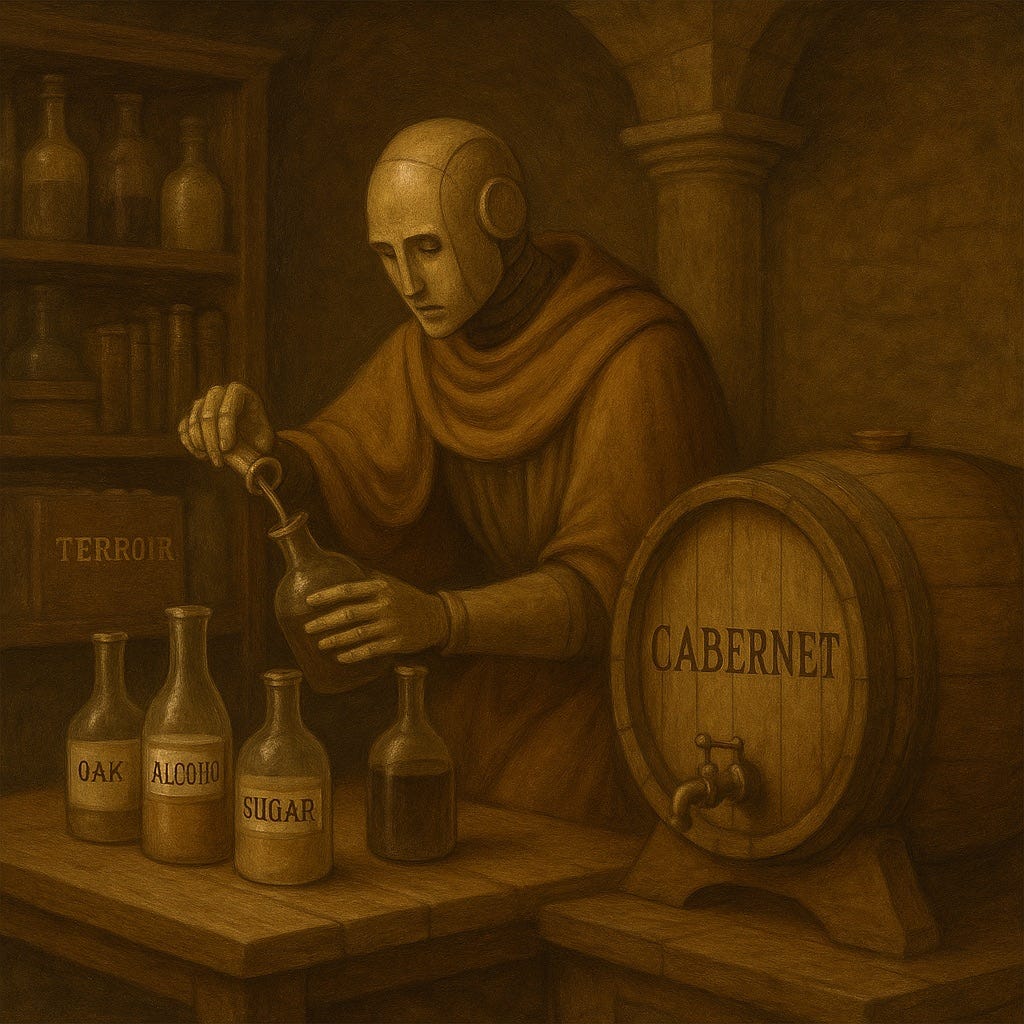

“Another thing that bothers me,” he said, “is that this thing says absolutely nothing about where it came from. It’s really only a big chewy red wine that has an awful lot of oak, and its acidity is really low. It wouldn’t do very well with food, and it actually tastes sweet.”

I agreed. As did two other judges. The organizer was miffed since the magazine review had been so effusive. Six of the seven judges agreed that the magazine had missed on this wine, which we considered to be worth maybe $10 to $12 per bottle, not the exalted (near $100) price to which it had risen.

Assume for a moment that you had read the review of this merlot and believed the extremely high score it received. If you had tasted it before buying any more, you might have been dissuaded from buying more. Most people did not do that. It sold out instantly.

This doesn’t prove anything, but it implies strongly that a score that may not be accurate often leads people to buy some poor wines for far too much money.

To many people in this world, the key factor in a red-wine-buying decision is concentration, power and extract. Big sells. Balanced wines don’t. Intensity is necessary for most U.S. buyers. Here are a few of the terms I found in a U.S.-based wine magazine.

A pinot noir scoring 94 points: “High extract, high alcohol.”

A syrah scoring 94 points: “…enormous…”

Another syrah scoring 94: “…amazing extract…”

An Oregon pinot noir scoring 93 points: “… amazingly rich … smoky oak…”

A California sangiovese scoring 93: “Dense and concentrated…”

What was missing in these glossy-magazine reviews was any sense of the style that once was mandatory for a fine wine: regionality. Or the grape’s personality. Or the house style. Or the ability of the wine to pair with specific foods. Something more than weight.

In most European wines (Europe must be considered to be the stylistic models for all of the varieties we use in California) some form of distinction, or distinctiveness, should be at play. And in Europe, one of the critical factors in determining quality has historically been a regional identity.

The French use the term terroir, a rough translation of the taste of a place. The terroir of a wine is almost always an essential element in all great (and most regional) wines from Europe, where the paradigms arose.

To French wine producers, a wine’s terroir is even more important than the varietal precision. If the grapes are grown properly, the varietal-ness is subsumed within the regional identity and becomes intertwined with it. They become one.

In California and throughout the West Coast, from about 1997 to today, we seem to have lost much of those unique terroir-ist characteristics as more and more producers, seeking the higher scores that seem inevitably to accompany bigger and bigger wines, choose to pick grapes far later than respect a taste of place.

Sad fact: In this country, taste-of-place red wines do not sell as well to most average American wine buyers as do wines of intensity and ultra-ripeness.

And who are the people buying the larger, beefier red wines? In my view, they tend to be unsophisticated. They absorb the alcohol for its weight and succulence. They do not appreciate tartness, nuance or sophistication. The prefer the finale of the “1812 Overture” to “A Lark Ascending.” They do not want individuality; they want intensity.

They are happy to have a sweet cabernet with their filet of sole or an oak-driven chardonnay with lamb chops. Far too often, red wine is drunk alone; food is unnecessary.

I never met George Saintsbury, wine author, journalist and professor of rhetoric, who died in 1933, but he might have termed most American wine-guzzlers “heathens.”

The American demand for massive reds kind of reminds me of the wave of interest in the Hummer a few years ago. The Hummer was not subtle or sleek; Pininfarina was not involved in its design. It was a testosterone-powered vehicle.

In the last two or three years, this trend toward big reds has displayed some fraying at its edges, but the current downturn in sales nationally has created an enormous backlog of red wines in warehouses that were made during the power period when bigness was in vogue. So the big reds are still out there, waiting for their day in the sun – as chilled cocktail wines.

Not long ago, I was offered four bottles of a good red Burgundy at a fair price. Before making a decision, I looked on the internet to determine the style of the producer. The comments indicated that this producer in Côte de Beaune made red wines that were lighter in color, a style of pinot noir I love.

Since Beaune is a French district laden with limestone soils from which dark red wines are an aberration, I was pleased to buy the wines – and even more pleased when I opened one and found it to be excellent – graceful and with regional character.

I perceive an increase in better balance and more personality in the red wines being made in California today. I’m finding that several cooler districts in California, Oregon, Washington and a few other places actually have decided that it would be in their best interests to fight the trend toward massiveness.

Here are a few of those locations:

Oregon: The Willamette Valley, south of Portland, has long been decreed as Pinot Noir Heaven. Most wine-lovers believe this to be so. But ever since my first visit to the region in 1976 to do interviews with the few winemakers who existed there, it was evident that trying to make darker, heavier PNs was a quest unlikely to reward anyone.

In interviews with David Lett at Eyrie Vineyards and Dick Erath at Erath Vineyards, both suggested that (a) white wines would probably be the finest wines that Oregon would produce, and (b) pinot noir had a future but primarily along the lines of Burgundy’s lighter Côte de Beaune. I tasted both wineries’ early-1970s pinots. Both were graceful and driven by personality, not weight.

I thought of terroir.

However, in the intervening years (more than 50 years and counting) I have found that Willamette Valley PNs that were darker and concentrated had more tannin than they needed. I prefer Oregon’s more elegant styles, which I see as Oregon’s greatest contribution to the breed.

Moreover, proving this point is the fact that Oregon today produces some of the most exciting red wine I have ever tasted. They are made from the grape variety gamay noir. Most of them are not heavy or clumsy. Indeed, they emulate the style of wine that both Erath and Lett adored in 1976.

Santa Barbara: Cabernet sauvignon and several other red wine grapes do extremely well in this coastal band that has several east-west valleys that provide marine breezes. This cooling climate can make for some truly distinctive wines.

But with both PN and cabernet, there is a unique and delightful terroir-ish herbal component that really plays against these wines being evaluated by people who are not aware of the distinctive style. Trying to evaluate a Santa Barbara cabernet using the same standards used to evaluate Napa Valley cabernet is a fool’s quest.

(Whereas Napa cabs generally do not have the staying power they once had, Santa Barbara’s older cabernets frequently shock people with their development.)

Some of the best Santa Barbara reds I have tasted, from either Burgundy or Bordeaux grapes, are a bit more difficult to dissect when they are young because of this subtle herbal influence.

The best people to judge these wines are those who live in Santa Barbara and have experience with them because they are familiar with Santa Barbara’s individualistic wines’ smell and taste and, critically, see what will take place after the wines get an appropriate amount of time after bottling.

One man who understood this dynamic perfectly was winemaker Jim Clendenen, who pioneered Burgundian-styled chardonnays and pinots that had the unbelievable ability to transmogrify into their European counterparts after just a handful of years. I opened a bottle of his 2009 chardonnay a few weeks ago with several wine-lovers. We all said it was an astounding experience.

Coombsville: Napa Valley’s small and relatively new appellation just east of the town of Napa is at the southern end of the valley and is influenced by ocean breezes and fog, allowing its cabernet vineyards to be oriented toward cooler-style wines, which tend to have a little less intensity and a little more of what Stag’s Leap District used to be.

Roughly 85% of the grapes growing in this smaller region, which is not terribly distant from Carneros, are cabernet sauvignon, merlot and cabernet franc. The style of wine produced here is still dense and concentrated, but there is a glimmer of cooler-climate influences that allow for an optimistic future that the region will be at the forefront when lighter styles come back into vogue.

Petaluma Gap: Bracing winds mark the distinguishing characteristic of this up-and-coming star region in Sonoma County. So much so that the Petaluma Gap Winegrowers Alliance uses the phrase “wind to wine” as a slogan. Although pinot noir and chardonnay have become key wines for the region, which was certified as an AVA just over seven years ago, several other terrific wines are being produced just 25 miles north of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Syrah grows brilliantly in this cooler P-Gap weather, and some parts of the AVA are even appropriate enough to accommodate blaufrankisch, a superb red wine grape with an Austrian heritage. Petaluma Gap is one of the most exciting wine-growing regions in the nation.

Anderson Valley: Quietly, this Mendocino County enclave has developed quite an enthusiastic following for its Burgundian leanings. In the last three years I have noticed a distinct shift toward more elegance and an attempt to display some of the unique cold-climate influences inherent in the soil.

This small region was identified 40 years ago as being remarkably similar to France’s Alsace. As such, gewürztraminer and riesling both have done brilliantly here. As chardonnay and pinot noir became more popular, the first styles to appear were a little richer, but now elegance has crept in to benefit consumers who appreciate more filigreed styles.

So, is terroir absolutely necessary for a fine wine to be called great? I once had a long discussion with Ridge Vineyards’ now-retired winemaker Paul Draper about this. It was Paul’s contention that without a vineyard site or a distinctive appellation to provide the impetus for a wine’s personality to show, it is extremely difficult to identify a wine as great.

I suppose that in a purely academic sense it is possible to call a wine great if it is a multi-region blend that displays a precise characteristic that the winemaker intended to exhibit – such as, say, a white Rhône blend. But one of the reasons that some wines from single vineyards are so highly prized is that they annually display that place’s fingerprints or body odor or some other je ne sais c’est quoi elements that experts swoon over – and pay big bucks to acquire.

—

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

Wine Discovery:

2015 Forlorn Hope Nacre Semillon, Napa Valley ($30): Semillon is a strange grape variety in that it can be made into a very nice but simple white table wine if it is harvested later. But as the Australians in their Hunter Valley have discovered, it deserves remarkable treatment by harvesting it extremely early and then making sure that the wine does not develop any richness at all. Napa Valley’s treasure Matthew Rorick understands semillon. In 2015 he did what the Australians have always done: harvest the fruit extremely early. This gave him a wine that has only 11.38% alcohol, almost identical to the best Hunter Valley semillons. I really love those wines, and I was transported back to the Hunter when I tasted for Rorick’s version. As with the Australian versions, this 2015 may be 10 years old, but it needs another decade before it ever develops what it will. I envision that it will be infinitely more complex than it is today. Now you get very faint melon and dried flowers that remind me of Australia but without any of the petroleum notes that sometimes creep in rosé Aussie versions. The grapes for this wine came from a 1950s planting by Andy Hoxsey just north of the town of Yountville. This wine is crisp and has a sort of minerally aromatic expression. The wine benefits from decanting and is perfect for pairing with oysters, smoked gouda or kippered salmon. This nontraditional winery has always intrigued me, and I’d like to know more about what’s going on, but I can never seem to reach Matthew.

Today’s Polls:

This Week's Word Challenge Reveal:

The correct answer is D: Subtle minerality in flavor.

The word sapidité comes from the Latin sapidus, meaning “having flavor” or “savory.” In French, the adjective sapide refers to something flavorful, and the noun sapidité captures the quality of being pleasing to the taste. Though recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary, sapidité is vanishingly rare in English usage — especially outside of technical or translated texts. In the wine world, however, especially among sommeliers and critics trained in French tradition, it carries a specific and evocative meaning.

In wine, sapidité refers to a mineral-tinged, savory liveliness — a brightness on the palate often linked to limestone soils, high acidity and restrained winemaking. It’s a hallmark of Chablis, Sancerre, grower Champagne and other wines that prioritize precision over power. It’s not about saltiness per se, but a refined, stony, mouthwatering quality that enhances food pairing and speaks of terroir.

Explore These Related Articles:

Browse All Napa Valley Features Stories

—

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.

If wines had to list ingredients, a lot of this would fix itself.