NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — There is a certain irony to be writing about any food but turkey during this week when one menu dominates the tables of the United States, but Worlds of Flavor, which took place Nov. 8-10 at the Culinary Institute of America at Copia in Napa, was a profound reminder that in our melting-pot country, adding your own touches to tradition is a way of telling your own story.

It is the 25th year that the CIA has presented this conference, turning the campus into “a crossroads of world food and culture,” as the CIA — our CIA — describes it. Each year they bring together chefs and restaurateurs with reps from the food industry, schools and the media for a dizzying three days that combine cooking demonstrations with conversations — and great food. One chef gives a talk about foraging in Tasmania, another about the new cooking of the American South.

Then everyone takes a break for a Marketplace lunch to sample the foods they have been discussing, from Thai tofu tacos to classic Spanish cheeses, and to meet the other attendees: A chef from Stanford teaching knife skills to astrophysics students, and his colleague is conducting studies on reducing food waste. Then it’s back to the auditorium to hear from an accountant-turned-gelato-maker Elisha Smiley, who has just opened a shop, Roman Holiday, in St. Helena.

“When we started this 25 years ago we had no idea how influential it would be,” said Jennifer Breckner, director of programs and special projects for the CIA.

Worlds of Flavor was the brainchild of Greg Drescher at the CIA, who wanted to make food traditions from around the world accessible to Americans, Breckner said. In turn, they became “re-energized into digging deeper into our own culture.”

The conference, originally hosted at the Greystone campus in St. Helena, moved to Napa after the CIA acquired the Copia site.

Looking back to the first conference in 1998, Breckner said the culinary world was dominated by the haute cuisine of France and the new California cuisine, driven by chefs such as Alice Waters, founder of Chez Panisse in Berkeley.

As Drescher guided the conference, they began turning a spotlight on traditions, chefs, restaurants and foods from around the world, with themes that ranged from an in-depth study of a specific continent or country — Africa, China or Spain — to worldwide explorations such as the “Culture of Deliciousness” or “Culture, Roots and Storytelling: Influences from Honduras to New Orleans and from Iran and Honolulu to San Francisco.”

The CIA staff spends a year planning for this annual “culinary think tank.” An exploration of street foods one year brought in an international collection of purveyors from Vietnam, Turkey and Mexico. Another year, for a focus on Japan, chefs from that country shared everything from the art of noodle-making to the theory and practice of creating kaiseki, the elaborate, exquisite Japanese haute cuisine.

For 2023 the theme was “Authenticity, Flavor and the Future.” Beginning with chef Ricky Moore, owner of Saltbox Seafood Joint in Durham, North Carolina, and ending with chef Musa Dagdeviren, owner of Çya Kebap and Çiya Sofrasi in Istanbul, the conference tackled the question of what — and who? — exactly is “authentic” and if it is even a useful word or standard for the culinary world.

“I’ve always trusted the CIA to teach people that there is more than what you grew up with culturally, said Moore, who graduated from the CIA in 1994. “I am into sharing cultures but showing respect.”

He showcased a recipe of his own creation, Hush-Honeys — spicy, crispy cornmeal fritters served with honey, goat cheese butter and lemon zest.

Moore was one of many chefs demonstrating the way in which they are taking traditional dishes and giving them their own touches, often finding inspiration in other cultures.

“How do you develop a recipe when you are not of that specific culture or ethnicity?” asked Breana Lai Killeen, a food writer, recipe developer, culinary nutritionist, farmer and founder of Vermont Culinary Creative.

“Is it out of bounds? No,” she said, “but be respectful, give credit and list the traditions.”

Also, she said, avoid words that can be offensive. Among the ones she listed were exotic, weird, Oriental and Kaffir lime.” (Due to the negative connotations of “Kaffir,” the Oxford English Dictionary recommends calling the fruit, “makrut lime.”) She would also get rid of descriptors such as manly, girly, white trash, guilt, skinny, binge-worthy, clean, cheap, all-American or even healthy.

“We are all learning,” she said.

Enrique Olvera, a 1999 CIA grad and now owner of Grupo Enrique Olvera, with restaurants in Mexico and the United States, summed it up: “You select, refine and adapt.”

Other chefs delved into new realms by creating dishes inspired by their own blended

backgrounds and life experiences.

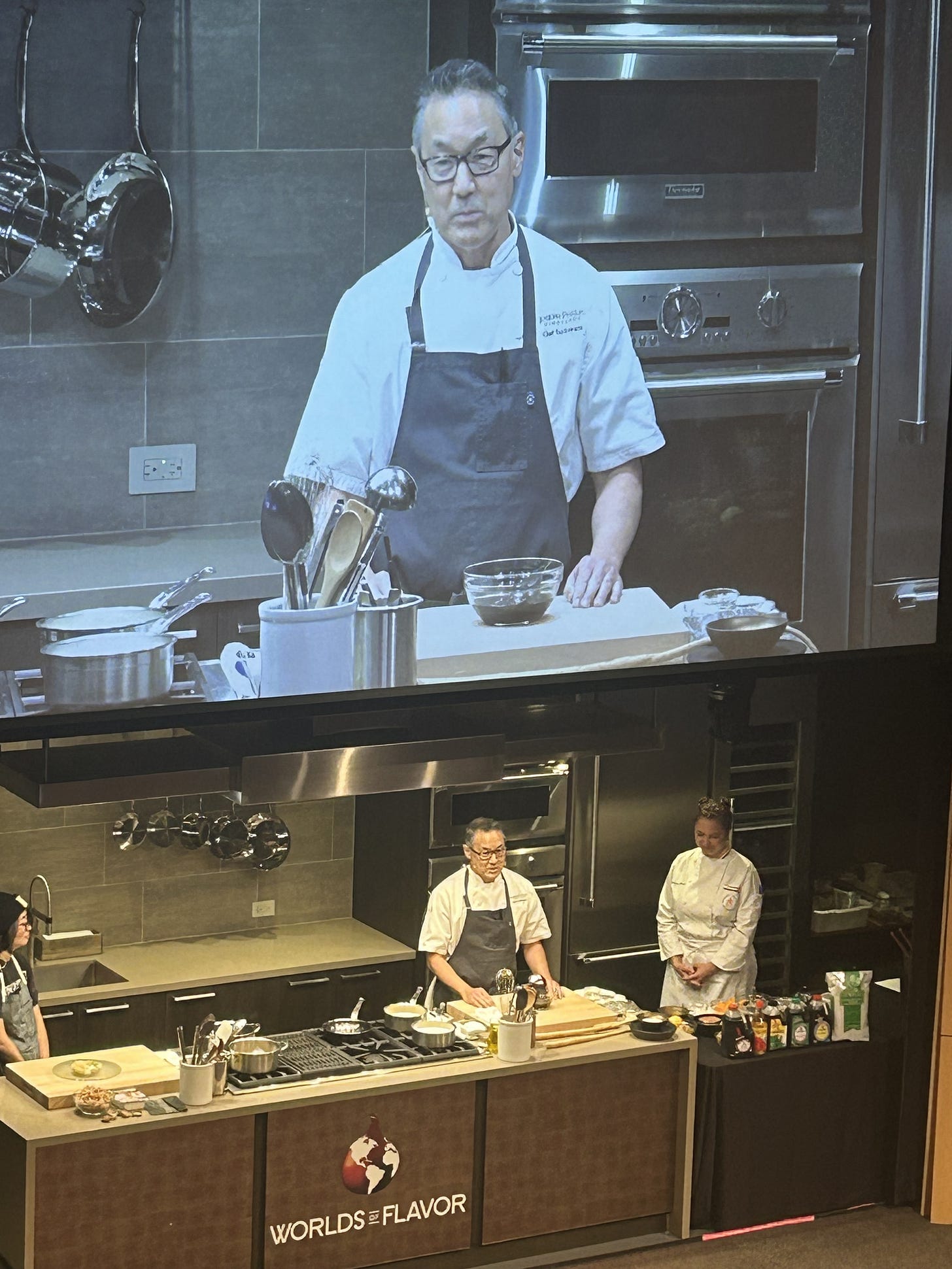

Tod Kawasaki, chef at Joseph Phelps Vineyards, discussed how he uses Japanese and Chinese elements learned from his grandparents as inspiration in the dishes he creates to showcase wines. And Sam Fore, who lives in Kentucky, draws on her Sri Lankan background to add a unique touch to the always-popular fried chicken, which she serves with a curry leaf sauce. Her Tuk-Tuk Fried Chicken “became a vehicle to tell people about my background,” she said. “It’s using ingredients from my childhood to make it accessible to others.”

One of the most unusual variations was adobo chocolate chip cookies, created by Abi Balingit, a Filipino-American home baker and author of “Mayumu: Filipino American Desserts.” The secret ingredients are soy sauce and apple cider vinegar.

“I don’t think ‘authentic’ is a useful word,” said Rick Martinez, who grew up in Austin, Texas. When he made his first trip to Mexico, he said he called his mother to tell her that the foods he was discovering were not the Mexican food he grew up eating. Now a James Beard Award-winning chef and cookbook author living in Mexico, he said he often gets complaints, most often from critics in the United States, that his food is not authentic.

“But if you put 10 home cooks in a kitchen and ask them to make a molé, you will get 10 different dishes. I make a molé the way my family likes it,” he said. “I honestly think ‘authenticity’ should go away.”

David Kamen, a 1988 CIA graduate who is now is director of client engagement for CIA Consulting, said as chefs seek to blend tradition with change, “innovation comes from asking ‘What if?’ What if we make fried chicken with rice flour or roast veggies on a rotisserie?” Maybe, he suggested, rather than authenticity, the word we should be using is “integrity.”

“When you are making food, you’re telling stories,” said Rupa Bhattacharya, who took over leadership of the Worlds of Flavor conferences after Drescher retired.

It was evident from the three days at the CIA that chefs are relishing the freedom to tell their own stories through their food.

The theme for the 2024 Worlds of Flavor, taking place Nov. 6-8 at the CIA at Copia in Napa, is “Borders, Migration and the Evolution of Culinary Tradition.” For more information, visit worldsofflavor.com.

Sasha Paulsen is a Napa Valley-based novelist and journalist.

Great article- I loved your words about "authenticity", "integrity", culture, tradition, "blending" etc. We can each incorporate new information gleaned from traditions different from our own every time we cook. Hopefully all things culinary evolve and change, much to our benefit, as we are exposed to new information and cuisines from around the globe. What a wonderful program. Thank you for sharing information about how we can each become more aware of food and cultures.