ST. HELENA, Calif. — Ever wonder who uses the St. Helena’s Sulphur Creek bed as a passageway through town? I have, so I decided to do a study with a series of motion-sensing cameras to find out.

Having lived near the creek for almost 30 years and studied water flows and fish habitat conditions during the rainy seasons as a volunteer for both the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Napa County Resource Conservation District, I became aware that plenty of non-aquatic species also rely on the creek for refuge, forage and migration. The biggest question in my mind was whether large mammals were using it as a corridor between the eastern county and the Mayacamas range west of town. With so many vineyards, roads, traffic, residential and commercial development in the area, crossing the valley can be a perilous journey for wildlife.

While I am not a trained biologist, my work with professionals on the Land Trust of Napa County’s WPI project at the Dunn-Wildlake Preserve and as a Natural Resource Volunteer/Wildlife Watch volunteer with CDFW, I was confident that I could organize a year-long study to get some answers.

Beginning in March 2022, I selected five sites in the creek to position cameras that would record active movement day or night. At regular intervals, I would retrieve and replace the SD cards with the images captured by each camera. As you might expect, there was a bit of a learning curve to go through. For example, when I failed to adequately clear vegetation within the camera’s field of view, I might end up with multiple shots of weeds or leaves that breeze-triggered motion was sufficient to activate the camera. Luckily, Megan Lilla from LTNC introduced me to specially designed software that streamlined the processing and cataloging of thousands of photos.

Some downloads contained as many as 6,000 images. Going through the images was still time-consuming but hugely more efficient than attempting to check them one by one. My study area ranged from the confluence of Sulphur Creek and the main stem of the Napa River on the east through the braided section of the creek west of the South Crane Avenue Bridge on the west, with intermediate cameras near Starr Avenue, Allison Avenue, and Gotts. After having two cameras stolen at the centermost location, I abandoned that site but felt the proximity of the rest of the sites bracketing the lost camera would not negatively impact my findings. For readers unacquainted with motion-sensing wildlife cameras, they can record both still and video images. For night activity, they take infrared pictures which appear as black, while daytime images appear in color. Each image is time and date-stamped down to fractions of a second. More modern versions of these cams than I used will even recharge themselves with solar and transmit the images, to obviate the need to visit the sites to replace batteries and SD cards.

The placement of the cameras relative to the base of the stream bed is important. I found that between three to four feet above the deepest part of the channel worked best for capturing good animal images. Unfortunately, I did not anticipate the December/January deluge that winter when the creek rose swiftly in the deepest and most down-cut sections between Highway 29 and the Napa River to the point where all but one of the cams were underwater. Even with chest waders, the flows were much too high and rapid to risk retrieving them. To my surprise, all but one of the submerged units were still serviceable after drying out, and none of the data was lost. After cataloging all the salient data with the specialized software and transferring it to a spreadsheet for analysis and interpretation, I was a bit stuck as I am not well versed in data manipulation. Luckily, a friend introduced me to a young lady from Angwin who loves wildlife and is a professional data analyst. Watching her help me organize my data was like watching and enjoying a virtuoso pianist playing a Chopin concerto.

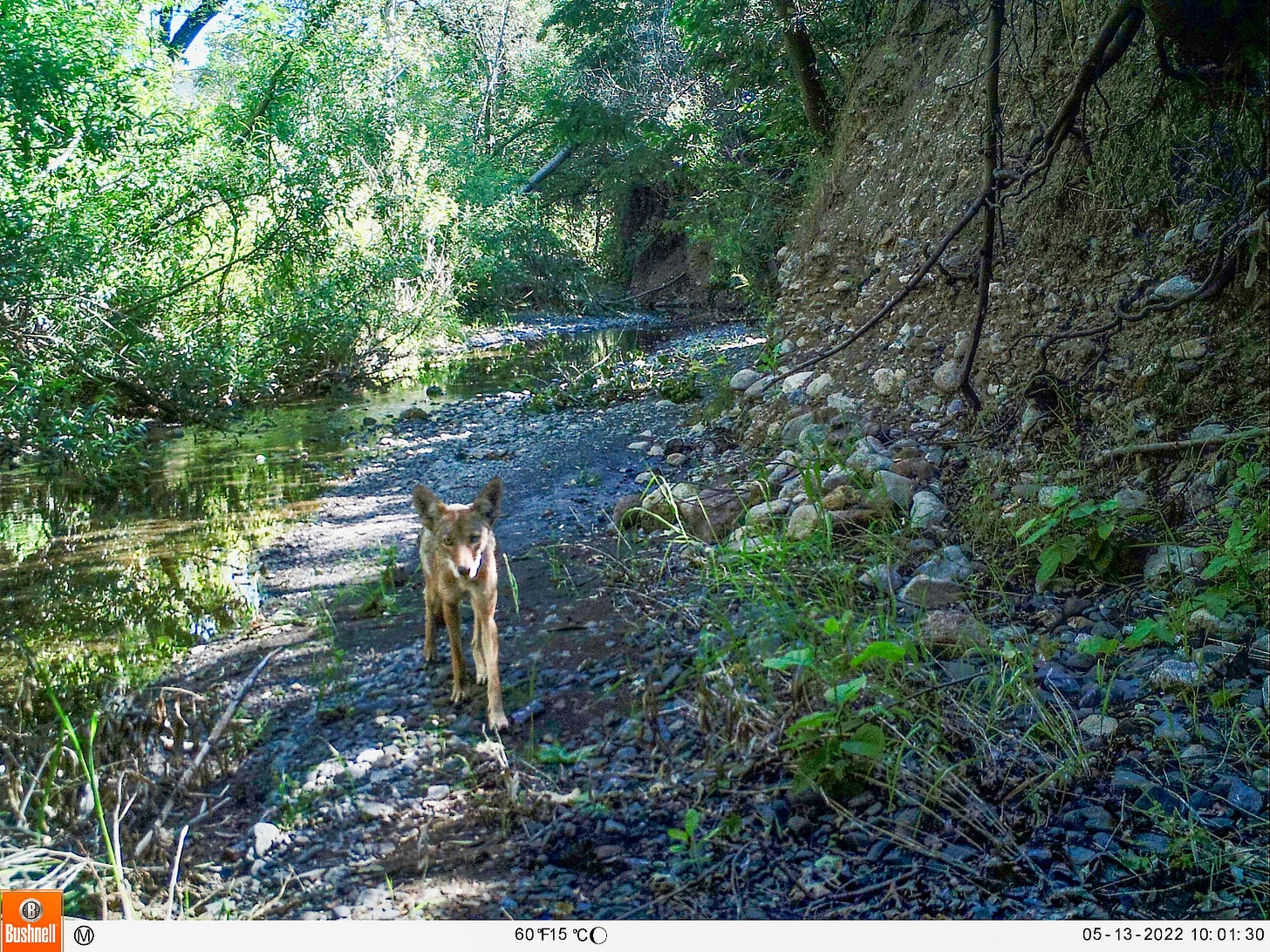

So, what did I discover? My cameras captured the following species: coyote, raccoon, possum, squirrel, skunk, cat, deer, bird, river otter, rat and human. The old cliché that “a picture is worth a thousand words” makes sense as I endeavor to share my findings with you. Besides the images in this article, I have been able to chart both the locations along the creek where the various species were active and also the times of day when one might expect to encounter them. I will begin with an overview of all users of the streambed including humans and then follow up with details regarding the more iconic animals (for any readers interested in delving deeper into my data, please feel free to contact me).

Probably the biggest surprise was the intensity of use by humans. In late spring and early summer, when the warm weather arrived and there was still plenty of water in the creek, many folks came to play and recreate. After the creek dried, it was still popular for young people and dog walkers. Following is the human use and density by neighborhood.

Coyotes, foxes, raccoons and cats (domestic and feral) were the most frequent non-human mammals captured by the cameras. With so many postings on Nextdoor, Facebook and the local press regarding coyotes, the following charts reveal when and where they are most active. It is interesting to note the heavy concentration of sightings in the central part of town between Vineyard Valley and Gotts, but, not surprisingly, they are most active between 8 p.m. and 1 a.m. Also, I couldn’t help but notice that the highest concentration of coyotes was in the Woodbridge area which also hosts the highest concentration of cats and raccoons — their natural prey.

Raccoons are very common and frequent visitors to probably everyone’s backyards here in St. Helena, but they really like the creek when there is water to both forage and wash their food. Most often, the cameras captured images of multiple members of a group at play or hunting.

Fox images were most frequently captured near Woodbridge and Vineyard Valley. They appear to be the most playful of all our four-legged neighbors and most are active in the late afternoon into early evening.

My study and data led to a few conclusions and surprises. First, while coyotes may well be using Sulphur Creek as a connecting corridor from the east side of the valley to the west, other large mammals do not appear to be. I failed to capture any bears, pumas or bobcats, and the only deer images captured were in the creek west of the South Crane Avenue bridge. The best surprise was spotting the family of American river otters trudging east in the dry channel near Woodbridge heading to the Napa River.

My yearlong observation of Sulphur Creek's natural thoroughfare reveals a vibrant array of wildlife quietly coexisting with the St. Helena community. The study highlights how stealthy coyotes, sociable river otters and other species are also integral, often unseen, members of our community. The findings emphasize the importance of natural passageways, which serve not only the necessities of these creatures but also enhance our connection to the local ecosystem.

Richard Seiferheld is a Cornell and NYU alumnus, former banker, and Napa Valley realtor turned dedicated wildlife volunteer and conservationist.

Disclaimer: Please note that the content of Richard Seiferheld’s article, including his exploration and photography of creek areas in St. Helena, was undertaken independently, as a citizen scientist and not commissioned by Napa Valley Features. Permissions for access were arranged by Mr. Seiferheld with the respective landowners, and his actions do not reflect the policies or practices of Napa Valley Features.

Our publication is not responsible for any liabilities or claims that may arise from the article’s content or the actions undertaken during its creation. Readers are reminded to seek their own permissions and adhere to local regulations when accessing similar areas.

I subscribed because of this article and hope for more that aren't wine, vineyard or upscale tourist focused. Am interested in the land, a variety of all the other people here and creatures.

Thank you Richard and Napa Valley Features for this fascinating study.