The devastating fires in Los Angeles County have left many in need, and thanks to our readers, we’ve been able to help. Because of your support, Napa Valley Features donated $300 in January to the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank. Due to the ongoing need and the generosity of our community, we’re extending this effort through February 15, with 10% of all new paid subscriptions going toward relief. Your support truly makes a difference — thank you.

The Spotlight

Welcome to “Under the Hood,” our exclusive Saturday series for Napa Valley Features paid subscribers. This week we delve into the growing threat posed by the Mediterranean oak borer, a silent invader that is devastating Napa Valley’s iconic oaks. With no effective chemical treatments and little regulatory oversight, arborists like Juan Esteban Restrepo and experts such as Bill Pramuk are racing to slow its spread before it reshapes the landscape and ecology of the region. What can be done, and what’s at stake?

Additionally, we’re diving into the latest data from our readers’ polls and providing insights from our economic dashboard, covering local Napa Valley, U.S. and global markets.

In addition, we feature "What We Are Reading," a section with a handpicked list of recent articles that provide a variety of viewpoints on issues important to our community and beyond.

“What We Are Reading” quotes of the day:

"If you can prove that there is a market, [growers] are fans of innovation." – Anne Kettaneh, in "Bordeaux gets alcohol-free wine shop as times change," Decanter.

"Even with all the [undocumented] immigrants, we’re still short on labor in our vineyards, fields and wineries."– Rolando Herrera, in "Sonoma, Napa county vineyard owners fear deportation of workers amid Trump’s immigration crackdown," The Press Democrat.

"As a collective culture, we’re moving away from drinking alcohol." – Keena Hanson, in "Could cannabis sales cannibalise wine?" The Drinks Business.

Decanting the Data:

The Silent Invasion: The Mediterranean Oak Borer’s Threat to Napa Valley’s Iconic Oaks

By Tim Carl

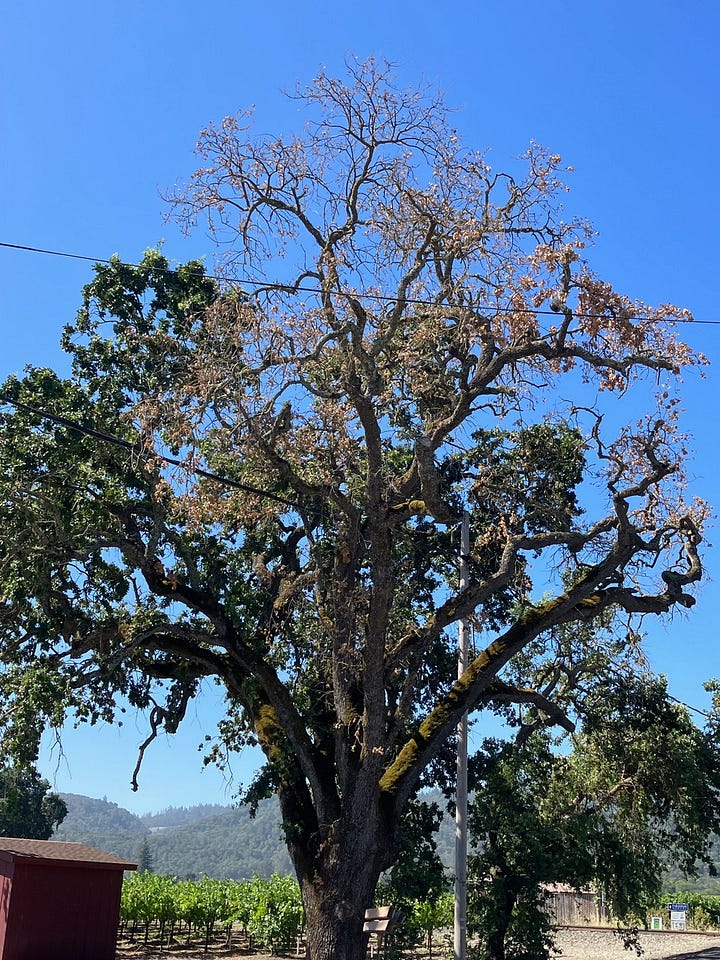

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — On the outskirts of Calistoga, arborist Juan Esteban Restrepo pressed his palm against the rough bark of an ancient valley oak. He didn’t need to look up to see what was happening — he already knew. The tree’s canopy was thinning, its upper branches brittle and dying. Small holes, no wider than a pencil tip, dotted the bark, each one an entry wound for a slow-moving catastrophe. At the base of the trunk, a fine sawdust-like substance, known as “frass,” had begun to accumulate — a clear sign of borer activity, the remnants of their destructive tunneling inside the tree.

“This is what we’re up against,” Restrepo said, shaking his head. “People don’t know it, but many of these trees are dying from the inside out.”

For years Restrepo has been caring for Napa Valley’s trees. His journey to becoming one of the region’s most sought-after arborists, however, was anything but conventional. Born in Medellín, Colombia, at a time when the city was synonymous with violence and upheaval, Restrepo found solace in nature. As a child he spent weekends in the countryside working alongside his grandmother in her garden. When he immigrated to the United States at 18, he pursued various jobs before marrying Bettina Rouas, owner of Napa’s Angele restaurant, and discovering his true calling — tree care and preservation.

Now, as the owner of Von Greiff Tree Care — a name chosen to honor his grandmother’s last name — Restrepo is facing what may be the greatest challenge to Napa’s oak woodlands yet: the Mediterranean oak borer, an invasive beetle threatening one of the key symbols of the region’s ecological and agricultural health. Beyond working with clients for fire mitigation, forest regeneration and landscape management, he has become an early advocate for protecting Napa’s oaks from this rapidly spreading pest.

An Unseen Killer

The Mediterranean oak borer (Xyleborus monographus) is a tiny ambrosia beetle, barely an eighth of an inch long, yet its impact is anything but small. First detected in Calistoga in 2019, the beetle has spread quickly, infesting valley oaks (Quercus lobata) and, to a lesser extent, blue oaks (Quercus douglasii).

Consulting arborist Bill Pramuk, who has been tracking MOB’s spread, says its presence is marked by dark, erratic tunnels carved into the tree’s inner wood. As the beetles burrow, they introduce symbiotic fungi that digest the wood, creating what is known as ambrosia — a food source for their larvae. But these fungi do more than provide sustenance. Some are pathogenic, accelerating the tree’s decline.

Like other ambrosia beetles, MOB follows a distinctive reproductive cycle. Females bore into trees, excavating intricate tunnel systems, or galleries, where they lay their eggs. Within these tunnels, the beetles cultivate fungi, which spread rapidly through the wood. Unlike typical wood-boring insects that feed on the tree itself, MOB larvae rely entirely on these fungi.

What makes the Mediterranean oak borer particularly difficult to control is its ability to reproduce parthenogenetically, meaning females can lay unfertilized eggs that develop into males and females. These siblings often mate within the natal gallery before dispersing, further accelerating population growth. This reproductive strategy allows a single female to establish a new infestation independently, even without mating, and potentially initiate multiple infestations within a single season. Such rapid and self-sufficient reproduction makes containment efforts exceedingly challenging, as a single beetle can give rise to widespread outbreaks in a short time frame.

“The first sign most people notice is canopy dieback,” Pramuk said. “A section of the upper branches will start to wither and turn brown. By the time the infestation is visible, the damage is often extensive.”

MOB vs. Sudden Oak Death: Understanding the Differences

While the Mediterranean oak borer is a growing threat, many in Napa Valley are more familiar with Sudden Oak Death, a devastating tree disease caused by the waterborne pathogen Phytophthora ramorum. Though both afflict native oaks, their modes of spread and impact differ significantly.

SOD thrives in moist environments, spreading via water droplets, particularly during rainy seasons. It primarily affects tanoaks (Notholithocarpus densiflorus) and coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), causing bleeding cankers and rapid decline. In contrast, MOB spreads through dry conditions, infested wood and human activity, targeting valley oaks and blue oaks. Rather than causing external lesions, it introduces fungi that compromise the tree from within.

SOD can be managed through quarantines and fungicidal treatments. MOB, however, presents a greater challenge. No chemical treatments have been proven effective, according to Pramuk, leaving proactive tree-health management and the strategic removal of infested material and not transporting firewood as the best available defenses.

How Did It Get Here, and How Does It Spread?

Native to the Mediterranean, the MOB has long coexisted with oak species that have developed natural defenses against it. But in California (and probably Oregon and Washington), where native oaks lack such resistance, the beetle has found a vulnerable new habitat. Scientists suspect it may have arrived through untreated wooden pallets, shipping crates or other solid wood packaging — one of the most common pathways for invasive pests.

Some have speculated that imported oak used in wine-barrel construction could be to blame, but Pramuk remains unconvinced.

“Barrel staves are heat-treated, which should kill any borers in the wood,” he said. “But shipping materials? That’s a different story.”

However it arrived, once established, the beetle’s containment has been hindered by inaction at the state and local levels. Unlike Sudden Oak Death, which is an “A-rated” pest in California, prompting extensive monitoring and containment efforts, MOB has no current state regulations to curb its expansion, as it is rated as a “B-rated” pest, meaning that management decisions are left to individual county agricultural commissioners rather than being subject to statewide regulation. Funding for bait-trap monitoring has been cut, according to Pramuk, and many utility companies and property owners unwittingly fuel the problem by leaving or transporting infested wood.

According to Restrepo, one of the biggest drivers of MOB’s spread is the movement of infected firewood.

“You see it all the time — someone cuts down a dead or dying tree and hauls the logs to another location,” he said. “They don’t realize they’re carrying the beetles with them.”

Pramuk added that improper tree removal has also accelerated the problem.

“Power line crews have taken down MOB-infested trees and just left the wood lying there [for people to grab],” he said. “That’s another way this beetle spreads.”

A Perfect Storm: Drought, Fire, Climate Change and the Edge Effect

Napa Valley’s oak woodlands are caught in a web of compounding environmental stressors that make them more vulnerable to threats such as the Mediterranean oak borer. Prolonged drought has significantly weakened these trees, disrupting photosynthesis and root growth. With depleted energy reserves and reduced defenses, oaks become easy targets for pests and diseases. Even after rainfall returns, full recovery can take years, leaving trees highly susceptible to secondary invaders such as ambrosia beetles and fungal pathogens. Symptoms of drought stress — wilting leaves, premature leaf drop and branch dieback — are often just the first signs of decline.