The 2023 growing season: Napa Valley edition

By Loni Lyttle, Director of Viticulture at Advanced Viticulture Consulting

In this comprehensive technical analysis for Napa Valley Features, Loni Lyttle, Director of Viticulture at Advanced Viticulture Consulting, along with the company’s founder, Mark Greenspan, delves into the specificities of the Napa Valley’s 2023 wine grape growing season. Their work distills the season's data into actionable insights, examining how this year's unique climatic conditions are likely to influence the region’s vintage.

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — “It was the best of vintages; it was the worst of vintages…”

2023 has been a weird one. While the rest of the nation got a taste of what hellish future awaits our grandchildren, here in California we enjoyed a cool spring followed by a temperate summer. In many areas this equated to prime growing conditions for high-quality grapes. In other areas, it didn’t. I wrote about the season more broadly on our own Advanced Viticulture blog, but I wanted to take some time to drill down on how this season played out particularly across Napa Valley.

Let’s start by looking at how growing degree days stack up in relation to previous years. GDDs are typically calculated by taking the average of the daily minimum and maximum temperature and subtracting a base number, in this case 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit). Let’s start with how these indices varied in the northern part of the valley, where temperatures are typically warmer.

As you can see, what started out as a colder than usual spring never really caught up. Around June 1, things were already 300 GDDs behind the previous year’s average and, as of the close of the growing season, the final tally was still trailing by a similar number of degree days in Calistoga.

As we move south to St. Helena, the cool spring gave way to a warmer summer that seemed to resemble 2020 towards the end of the season (minus the devastating wildfire).

In Oakville, the weather never caught up.

Likewise, in Oak Knoll…

Carneros was between 144 and 635 GDDs behind that of previous years, clocking in at fewer than 2500 GDDs this year by the end of the traditional growing season.

Early season struggles

This year, the cool season pushed back budbreak to what we used to consider a “normal” time. This was a welcome change to growers that got hammered during the ugly frost seasons that characterized 2022 and 2021. However, the cold weather didn’t let up, making for an interminable bloom period. The temperature dropped in early June, hitting some vineyards right as they started flowering. July warmed up, but it was already apparent that some places had lost over 50% of their yield to shatter.

The below graph shows average temperatures at a vineyard on Spring Mountain. Unfortunately for this grower, bloom lasted a solid two weeks during which time the temperature took a dive. Shatter was considerable there.

Let’s look at some hillsides…

This season has been quite a teaching moment in terms of meso and even microclimates. Some vineyards flowered at just the right time and produced abundantly. Others got repeatedly nailed. In some cases, we’ve seen great set and poor set in the same vineyard block.

Take that Spring Mountain vineyard featured above for instance. The blocks that survived with minimal shatter produced the highest quality fruit they ever have. Go figure.

Napa Valley is full of nooks and crannies of microclimates, so it is a fun place to explore weather-wise. Let’s look at how this season compares in a place like Mount Veeder.

One thing to note here is that GDDs stack up differently on a hillside versus the valley floor. The valley floor temperatures fluctuate more than hillsides, getting warmer during the day and cooler at night. At higher elevations, there is a smaller day/night differential with warmer nights and cooler days. Some of these warmer temperatures that push up the measurement of GDD occur during the nighttime, during which grapevine canopies are not photosynthetically active. This doesn’t affect bloom time much, but it certainly does affect sugar accumulation. At this location on Mount Veeder, the season clocked in at 3255 GDD, but I would take that with a grain of salt. The season was much shorter than usual due to late bloom and fruit set and the temperature accumulating after veraison provided considerably less bang for your buck than it would have on the valley floor. If you had a hard time ripening fruit on a hillside this year, this is probably why.

Let’s look at another high elevation area. Here’s how the season played out in Angwin/Howell Mountain.

Here the GDDs are on par with 2019, however a later budbreak and bloom meant the 2023 growing season was shorter even if it caught up by mid-summer.

Trying to catch up…

When you face-plant off the starting block, it’s hard to finish the race with any dignity… so I’ve heard anyway. The vines’ phenological cycle is mostly driven by spring temperatures. When that is late, the whole season gets shifted and making up for lost time is just not going to happen — eventually fall comes and days get shorter and colder. Where we saw poor set (and in many cases even where we saw good set), we also saw uneven berry development. When berries set at different times, even within a cluster, the clock starts ticking for them at different times and persists throughout their development. Veraison was very late this year and when it finally arrived it also took forever to wrap up. Seems like there were hard, green berries remaining on clusters for weeks even after veraison had begun.

Why was this year spectacular?

For many growers, 2023 has been a fantastic vintage so far both in terms of quantity and quality. The quantity side of the equation probably owes itself to the abundant rainfall we got this winter and early spring. Vines went into the spring with a nice full soil profile. During previous drought years, growers have relied solely on early season irrigation to promote canopy development, if they irrigated at all. Not only did vines have plenty to drink this year, they also had access to more nutrients than usual since they could tap into the entire soil mass as opposed to just the small volume of moist soil under the drip emitters. If you managed to avoid bad weather during bloom, you probably had good set because you had a nice big canopy to support flowering. If growers managed their crops properly, they avoided some of the uneven fruit development and potentially overcropped vines.

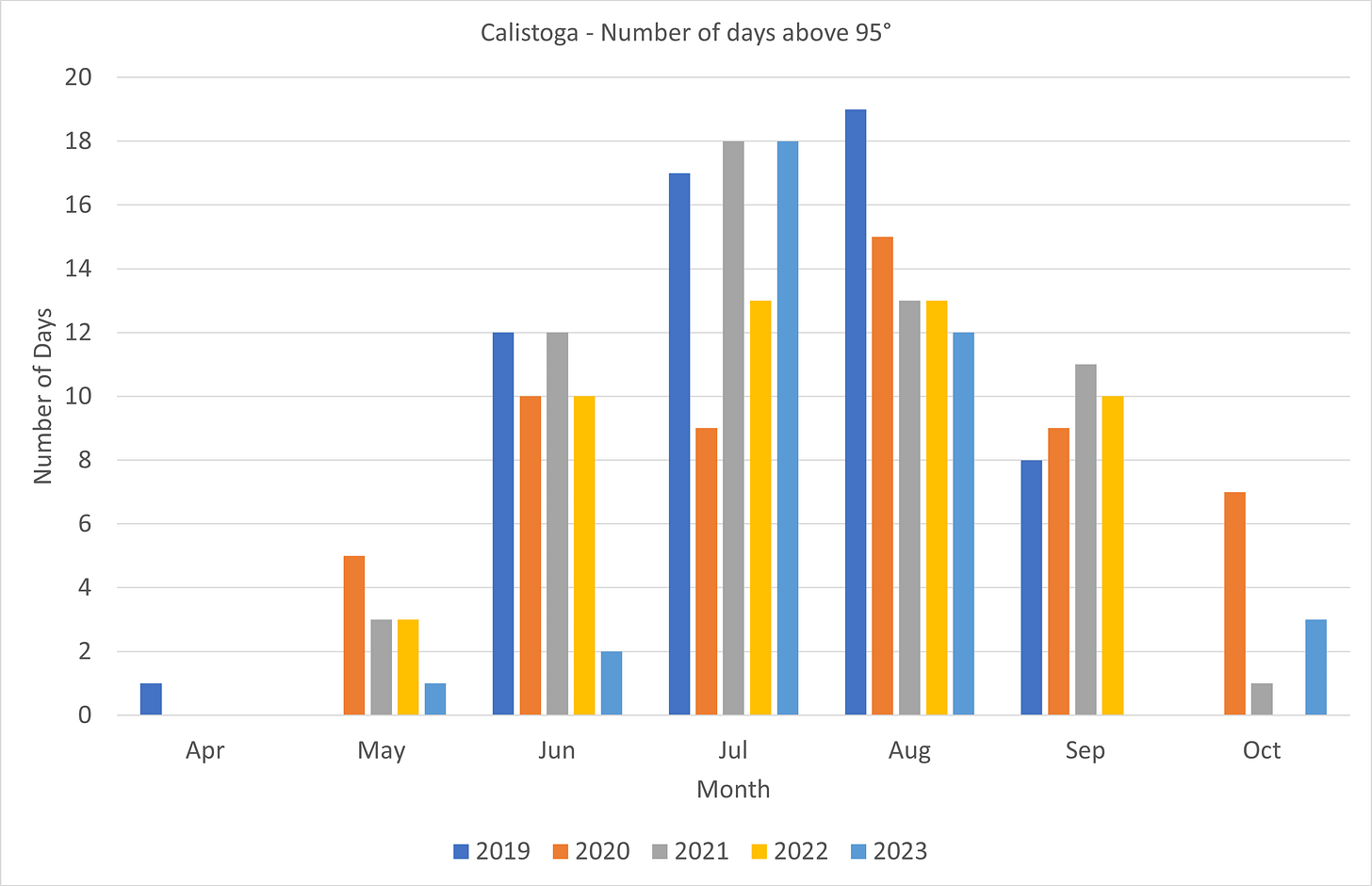

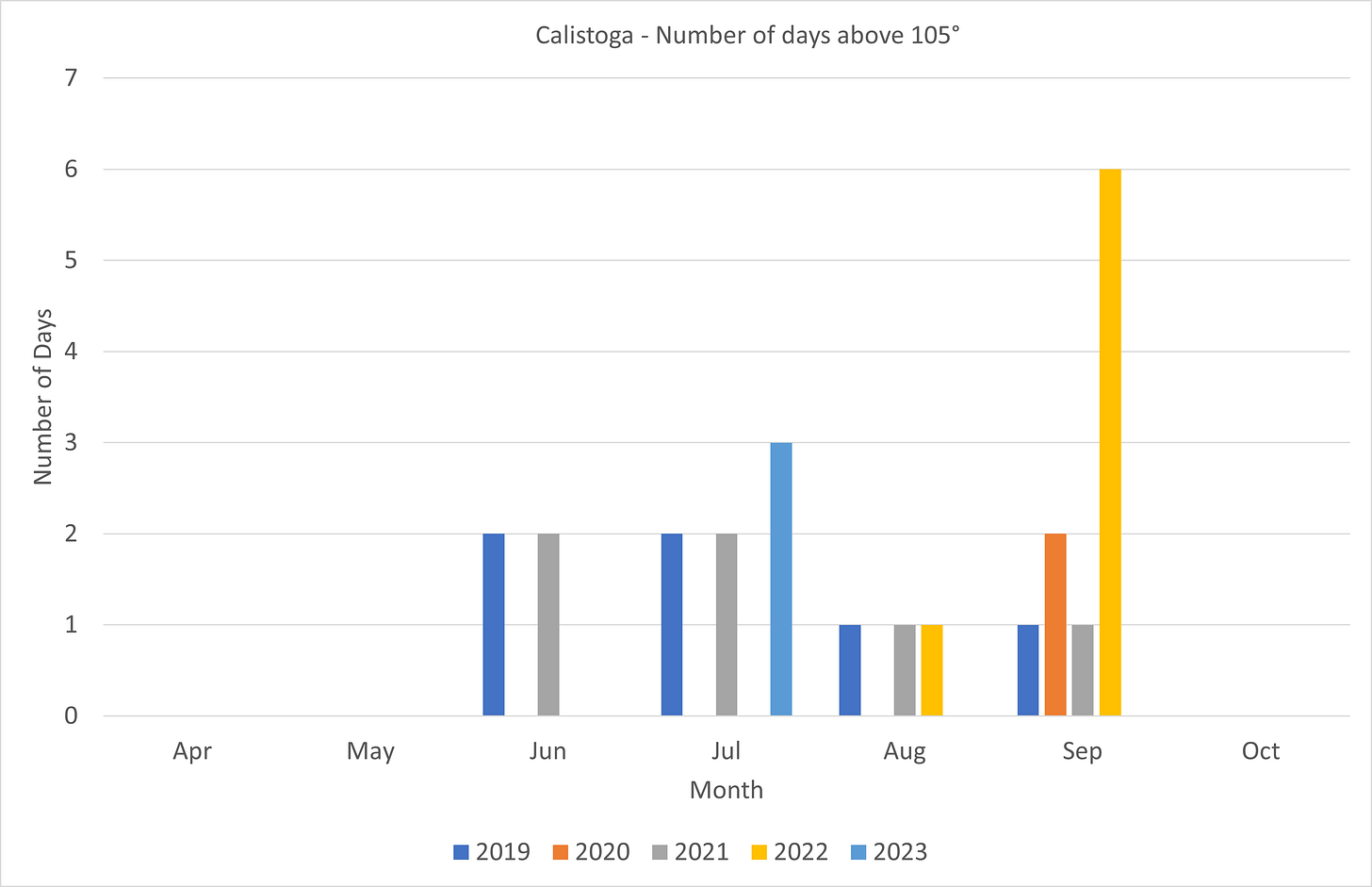

Weather extremes were markedly absent this year. If anything, that is why 2023 is looking like a great year for so many. Grapevine photosynthesis is dramatically curtailed at temperatures above 95 degrees. Anything higher than 105 degrees can cause irreparable damage to the grapes’ ability to mature fruit, not to mention the damage it causes to the fruit itself. This is what happened in the summer of 2022 and the spring of 2021 with expectedly unfavorable results. If sugars seemed to accumulate steadily in 2023, as some growers observed, it’s just because nothing went horribly wrong, as opposed to everything going fantastically well.

Last year, Calistoga got hammered when September temperatures reached over 110 degrees. The below graph shows the number of days above 95 degrees experienced in the past five years.

…and the number of days above 100 degrees…

…and days over 105 degrees.

In a place like Carneros, however, temperatures are typically cooler and the varieties cultivated are harvested earlier. The fact that this season was cooler may not have been as much of a relief to Carneros producers as it has been to cabernet producers up-valley.

Other quality considerations

Going into the season with a soaked soil profile is a double-edged sword. While you want a nice no-stress environment for your canopy development and bloom, you want your vines to be nice and water-stressed from lag-phase through the end of veraison. This promotes phenolic development, which we want for red varieties. Depending on your soil’s water-holding capacity, you may not have gotten there in time. Those I’ve spoken to in Napa say that so far wines are showing fine elegant tannins and good flavor, but perhaps lacking in the intense structure you want to age for decades, as tannin levels are generally lower than normal. It depends on what wine you’re trying to make and more importantly, who you’re trying to sell it to.

A late harvest season means you might catch rain, and we did — at least a little. Cabernet is pretty rough and tumble and can survive some late season rainfall. However, some growers of thinner-skinned varieties panicked and raced to harvest. I think that was a mistake, albeit an honest one. Back when I was in Italy, we would get torrential rainfall every fall that would often divide nebbiolo producers into those that harvested prior and those that harvested afterwards. Sometimes it paid off to wait and other times it didn’t. Did it get botrytis? Absolutely. Outside of California the tolerance for imperfect fruit is far more lenient, mostly out of necessity. I tend to prefer adequately ripened fruit to fruit that is underripe. Unfortunately, I don’t see attitudes towards botrytis changing anytime soon, especially not in Napa.

In hindsight

If you are normally someone who harvests late, you may have found yourself out of luck and out of time this year. In some parts of California, I’ve attributed poor ripening to overcropping. I doubt this is a problem in Napa where winemakers demand significantly reduced yield justified by high bottle-prices.

One mistake I did see was cutting off the water when growers shouldn’t have. The only thing that can increase sugar in grapes is an active canopy. An elongated season means that you need your canopy to hang in there for the long haul. Otherwise, you can rely on dehydration to push up your brix, but that comes with a whole lot of other problems. If the canopy is senescing, all those yellow leaves export their nutrients directly into the berries. This includes potassium. I hear every so often winemakers scratching their heads over a fermentation with high pH and high TA, and I think this may have to do with grapes from a senescing vineyard. The chemistry just goes wonky.

This was not a year to panic. Many growers cut water in early September when there was still time to ripen your fruit naturally as opposed to letting it dehydrate until it reaches desired brix levels. There’s an argument that cutting the water causes the vine to go into some kind of “ripening mode.” The plant hormone abscisic acid, which is triggered by stress, is important when it comes to initiating the ripening process (by stimulation of secondary metabolic enzymes), but not when you need to finish it. Sugar is a primary metabolite and is a product of good old photosynthesis. Photosynthesis needs water and if your canopy is senescing due to late-season water stress, there is simply no sugar to export to your grapes.

Conclusion

Unlike other years, 2023 wasn’t a complete disaster across the board although it did present some unique challenges. I cannot wait to taste this vintage!

Loni Lyttle is director of viticulture at Advanced Viticulture Consulting. Mark Greenspan contributed to this article and is the founder of AVC.