Part 2 of 3 (click here to read Part 1)

NAPA, Calif. — Once the rice is grown, harvested and dried, the process of sake production can begin. The first crucial step for premium sake production is milling away the outer rice layer. This determines the category and style of the finished sake.

There are three levels of premium sake. The highest or most polished is Daiginjo (Dai means big, so big ginjo). For this tier the sake grain is stripped away from 50% or more of the outer layers, revealing the shimpaku, or heart of the grain, and delivering elegance and purity. This is where the comparison with wine gets tricky.

The Daiginjo style is all about elegance and is generally the most expensive in the bunch. When compared with wine it would be more like Grand Cru Burgundy rather than a thousand-dollar Cult Napa Cabernet.

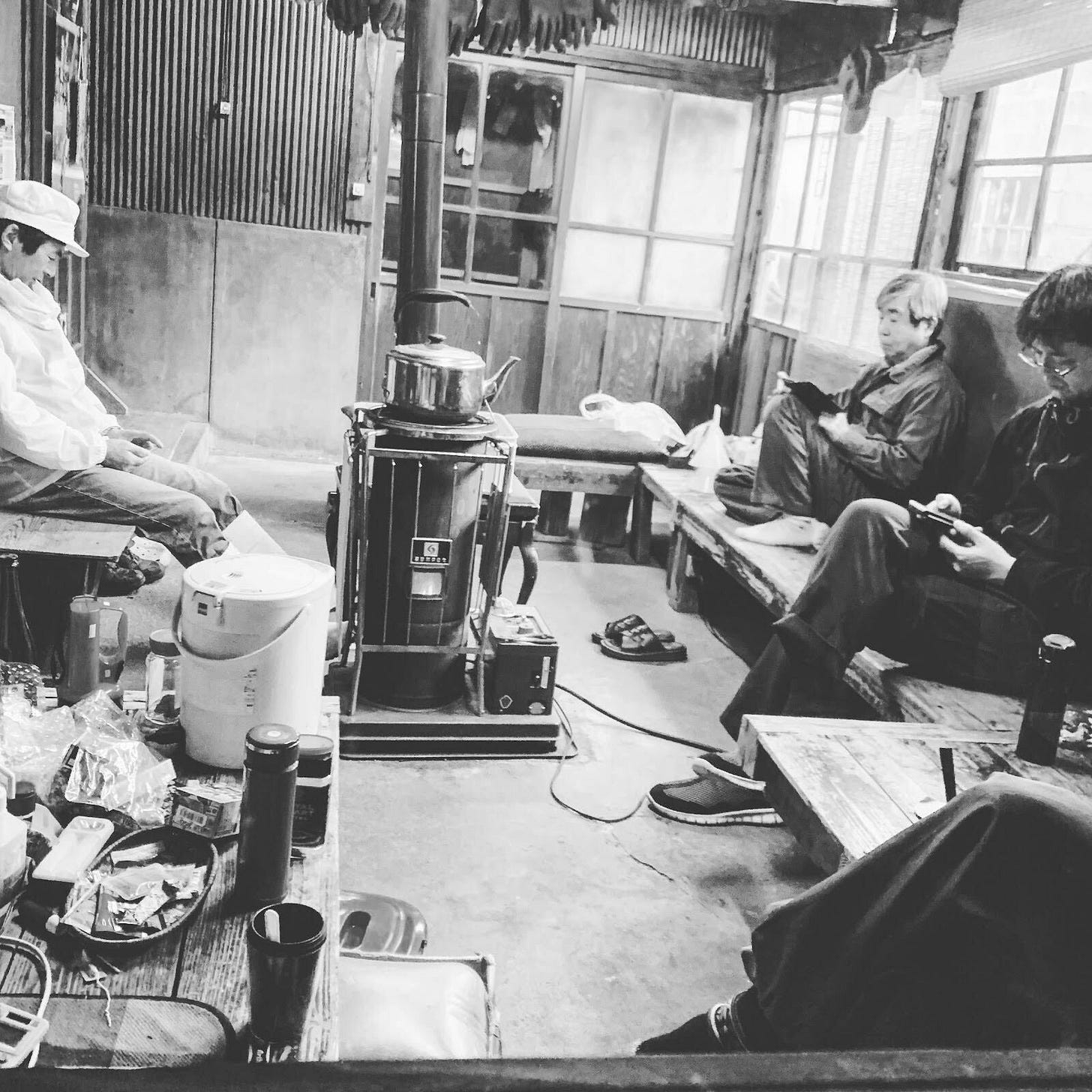

Gasanryu Gokugetsu Junmai Daiginjo "Mountain Stream" ($57, 720ml) from Shindo Shuzo in Yamagata is a stellar contender and a must-try. I had the pleasure of working at the brewery earlier this year alongside sake guru Stuart Morris, who makes a small batch of sake every year. I learned valuable knowledge by having this hands-on opportunity.

The middle category is Ginjo. To achieve this tier the rice must be milled 40% or more. This tier is all about versatility, complexity and balance. Ginjo shines a light on the character of the rice along with the house style of the brewery, methods of production and ingredients used.

It is like a well-choreographed dance where all the elements are in play and singing. It is more like a Bordeaux blend in delivery.

Katafune Ginjo Genshu, Niigata ($45, 720ml) is a legitimate example of the category from one of the most celebrated sake producers in Japan. It exudes charisma and has no lack of flavor.

The third level involves less milling on the rice grain, allowing the sake to retain more flavor, structure and “terroir.” By choosing to leave more of the starch, the style tends to have more earthy notes with some sakes highlighting forest floor, mushrooms and cocoa richness. This level is called Junmai or Honjozo and in theory could be compared to a Northern Rhône Syrah.

An ideal example of Junmai sake level is Shirataki Noujun Uonuma Junmai from Niigata ($37, 720ml). This sake captures a masculine character with candy cap mushroom notes and a hint of cocoa spice. Once milled to the desired level, the rice is thoroughly washed, soaked and steamed; then, a portion of the rice heads over to a saunalike room called koji muro.

In this sacred place of the brewery, steamed rice gets koji spores sprinkled on in a ceremonial fashion. Once it is evenly covered, small bundles of rice are wrapped like a baby and positioned in cubbies. During this period koji starts doing its essential and irreplaceable job of converting starch into sugars for the yeast to feast on later and convert into alcohol.

Once the koji rice is ready, the shubo starter starts taking shape with additions of water, steamed rice, koji rice and yeast. In the case of sokujo, lactic acid is introduced to ensure clean sake and a faster process.

Over the following days additional portions of the four ingredients are added as the fermentation kicks off. Once fermented, the sake gets pressed to separate from the kasu (lees). The most popular pressing methods are via assaku-ki, an automatic pressing machine that allows for control and precision. Fune is an old-school artifact. Imagine a coffin-size wooden box with a press on top that functions like an old-school tortilla maker. The sake, in small fabric bags, is placed inside the box, and the filtered final product comes out of a spout.

The third most relevant and usually most exclusive and expensive is Shizuku. In this process the sake goes into bags that are hung up. Without added pressure, the free-run juice gets captured into its purest form. Shizuku gets low yields, and the lengthy process makes it the Tête de cuvée style. One of my favorite Shizuku sakes is Toko Divine Droplets Junmai Daiginjo Shizuku from Yamagata ($80, 720ml)

Once pressed, sake gets filtered to remove small particles. Initial pasteurization then begins, followed by a storage period, a second and final step of pasteurization, and bottling.

Editor’s Note: In the next in the series, Eduardo Dingler will talk about more terms to know. Dingler is a Napa Valley-based wine writer, wine judge and sake aficionado. Follow his sake journey @sakedrinker