NAPA, Calif. – I’ve been a fan of rosé wines since the mid-’80s, when I spent part of July in Saint-Tropez in Provence at a friend’s villa. We drank little but local rosé against the perfect backdrop of warm weather, sunny skies and a slightly decadent lifestyle.

Few people took rosés seriously back home, however, often lumping them together with sweet white Zinfandel, a wine that was extremely popular, much to the disgust of wine snobs and many critics.

When I moved to Napa Valley in 1997 and wrote about the wines here, I soon learned to largely ignore these delightful wines. The situation has certainly changed now, however, and rosés have become the fastest-growing category of wine.

Last year I attended a seminar at Napa Valley Wine Academy about rosés made by local winemakers and wrote about them. They were a bit out of the mainstream of the rosé market due to focusing on local grapes such as Pinot Noir and mostly making fairly expensive wines (for rosés) to entertain their wine club members and tasting-room customers.

This year I noted that the academy was having a rosé masterclass taught by Peter Marks MW, whom I’ve known since he was the early wine expert at Copia. I knew that he was truly an expert in wine, so I decided to attend that class, too.

An informative seminar

This seminar was focused on the broad market. Rather than winemakers giving their take, Marks gave us an interesting lecture about rosé wines. Though I feel that I know quite a bit about wine as a former home winemaker and longtime writer about wine technology as well as wine, I learned a lot.

After the talk we tasted, but first let me summarize a few of his comments.

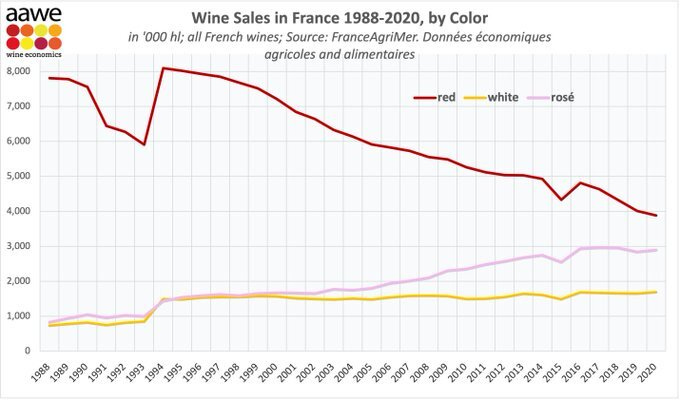

One, rosé is indeed booming, as he demonstrated in charts of growth.

Sales in the United States have grown 10 times from 2010 to 2020, and they’re growing faster in the United States than in France. Now one in 10 bottles sold worldwide is pink but in France one out of three as red wine sales drop. Rosé outsells white in France, in fact.

I’ll skip the history except to note that rosés have been around at least 5,000 years but didn’t take off here until about the 1990s. Marks noted that Rosé Prosecco, which wasn’t allowed until a few years ago, has really taken off.

“There has never been a better time to drink rosés,” he commented. “Rosé is refreshing, appetizing and good with food, particularly as we eat less beef.”

Though quality is better than ever, Marks warned, “There’s a lot of mediocre rosé out there.” It makes me wonder if a “Sideways” moment will hit the market as it did to Merlot.

On the other hand, though climate change is a threat to many existing vineyards, it may favor rosés. They are ideally picked early to provide sufficient acidity and low alcohol. Deep color and high alcohol obviously aren’t desired.

How rosé wines are made

Rosé wines are generally made via two methods. One is the traditional way of pressing fermenting red grapes when the must is lightly colored. This can take as little as a few hours. This allows the winemaker to pick the grapes at the optimum point with lower sugar -- hence lower alcohol -- and higher acidity, both considered desirable for rosés, particularly with food and to refresh.

The second method is called saignée, or “bleeding.” Here some of the must is drained quickly from fermenting red wines in an attempt to concentrate the color and flavor of the red wine.

That means the rosé has the same higher sugar and lower acidity as the red wine. Though that isn’t optimum from a traditional viewpoint, obviously many people like more alcohol and lower acidity.

This also leads to higher tannin, or “structure,” as winemakers euphemistically call it.

The most obvious way to create a rosé, blending red and white wines, is used for sparkling wines as the second fermentation can leave inconsistent colors but is not generally used for still wines. (Pedantic note: Some red wines traditionally included a bit of certain white grape juice to create deeper, more stable red wines. That was true in the Rhône Valley and Tuscany. Modern cultivars have largely overcome that weakness in the grapes, however.)

And some grapes like Pinot Grigio are really pink, so you can make rosés by fermenting their fruit like conventional red wine, but that’s fairly rare.

What grapes are best?

Many grapes are used to make rosé wines worldwide. Different regions use different grapes, but the most popular rosés are generally some blend of Grenache/Garnacha, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Cinsault, Carignan/Cariñena, Counoise and other grapes popular in southern France and Spain, even a bit of Cabernet Sauvignon.

In some cases, winemakers just use what they’re growing for other purposes. That’s why some local producers use Cabernet Sauvignon, I suspect.

On visits to Abruzzo and Puglia, for example, I found that traditionally winemakers didn’t grow many white grapes, so people drank red and rosés, the latter ideal with the seafood that is so popular in those coastal regions. Puglia now, however, is a big source of white wines.

Since we’re in the weeds of winemaking, we should mention two other issues: malolactic fermentation and wood.

ML occurs naturally in many wines, reducing their acidity by converting malic acid to mellower lactic acid, but good sanitation and cool temperatures can generally prevent it. It provides a bit of a “creamy” taste. Again, some people like those wines, but traditionally rosés were refreshing, which acidity favors.

Likewise, few rosés were traditionally oak-flavored. They were fermented and briefly aged in stainless-steel, concrete or old neutral tanks. With many wineries wanting to charge more for their wines, they sometimes tart them up with new oak barrels to try to make them like pink Rombauer Chardonnays and brag about the barrels and aging.

Rosés range from almost white to almost red, with the light tints favored in Provence most popular these days.

Tasting the 12

At this point we got to taste 12 wines from around the world. (We had a bit of Schramsberg Brut Rosé when we arrived, and you can’t do much better than that.)

Aside from the delicious 2015 Louis Roederer Rosé Champagne, which costs $115 per bottle, the French wines cost $20 to $28 with those from elsewhere mostly cheaper. (There was one outlier.)

I’d never had rosés from Beaujolais, Sancerre and Chinon, but now I have and they were fine.

But the $20 Chateau de Campuget from Costieres de Nimes, the most popular rosé in the United States, did exactly what I wanted in a rosé. It was tasty, refreshing and perfect for food.

The darker Tavel rosé from Chateau d’Aqueria Rosé was $22 and well worth it. It’s easy to see why Tavel was popular even when lighter rosés were not.

Other wines from Austria, Greece and Chile were comparable, and I’d drink them any day. The Austrian was $23, the others less than $20. Many sommeliers love Austrian wines, but I remain unconvinced.

Borsao Rosé from Campo de Borja in Spain was a real bargain at $8, and my personal favorite was the darker red Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo from Fantini at $16. I must admit that I’ve been to Abruzzo twice and that may color my tastes. Cerasuolo means “cherry-colored.”

The outlier we tasted was a $39 Law Rosé from Paso Robles. It is grown at 1,500 feet close to the Pacific and is a fine wine, but is it worth twice what most of the others were? Not to me.

Then Marks threw in a “mystery wine” that we tasted blind. It confounded two of my cherished beliefs about rosés: that Napa’s not a good place to grow them climate-wise and that Cabernet Sauvignon doesn’t make good rosé.

It turned out to be an excellent Honig 2022 Cabernet Sauvignon Pink, which is almost everything you want in a rosé. It’s not hot or tannic and has a very light color and delicate taste. In truth, I thought it was from Provence.

Unfortunately, it reinforced the other reason not to grow grapes for rosé in Napa: cost. The wine is $35, but they donate part of the proceeds to fighting breast cancer. This includes helping St. Helena Hospital provide mammograms for women who don’t have insurance.

My overall takeaway from the class: Don’t hesitate to try different rosés. They don’t have to cost that much, and there are plenty of good ones out there. One suggestion, however, is to look to the regions that aren’t so trendy, like the Rhône, Languedoc and Corsica instead of Provence and to regions outside France – or California – for the best values.

Napa Valley Wine Academy offers classes for professionals and wine-lovers. For more information, visit here.

If you’d like to find out more about events in the Napa Valley, subscribe to NapaLife, my weekly newsletter that focuses on news and events about food, wine and the arts – visual, literary and performing.