Napa Legend Carl Doumani Dies at 92

Owner of Stags’ Leap Winery, Founder of Quixote and Mezcal Pioneer

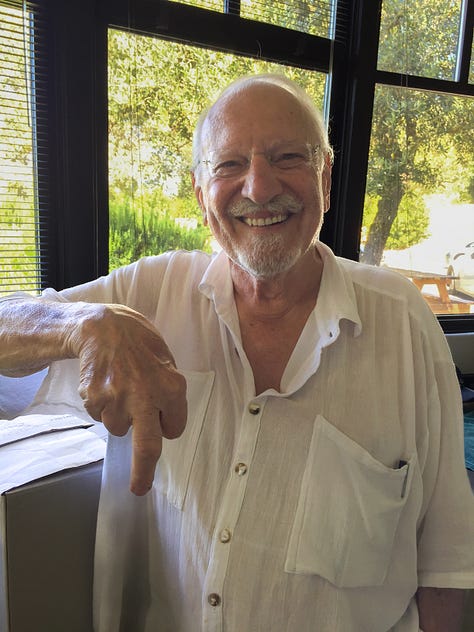

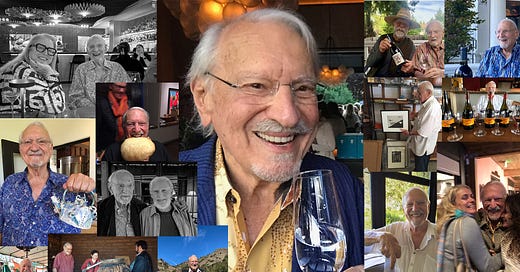

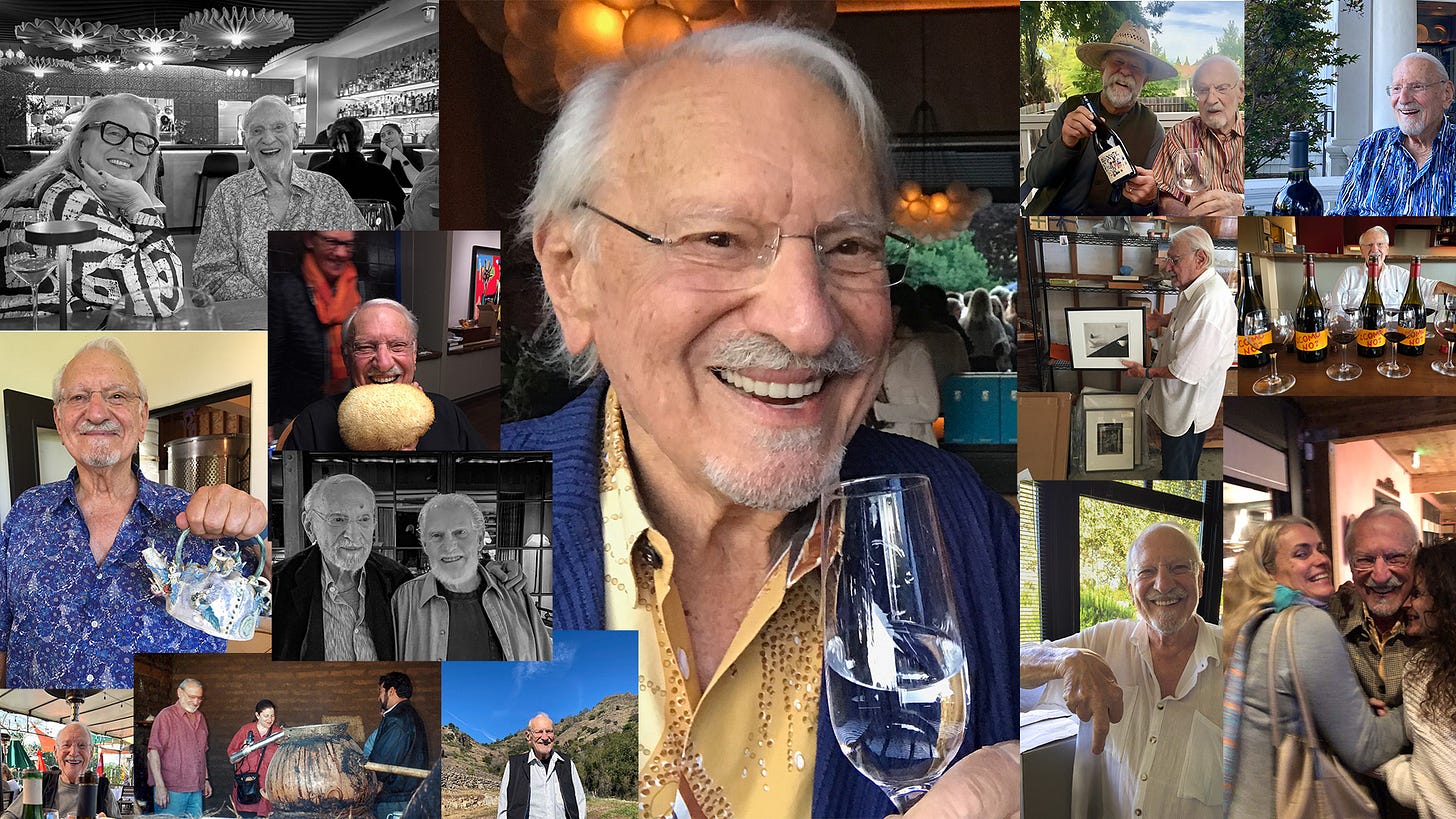

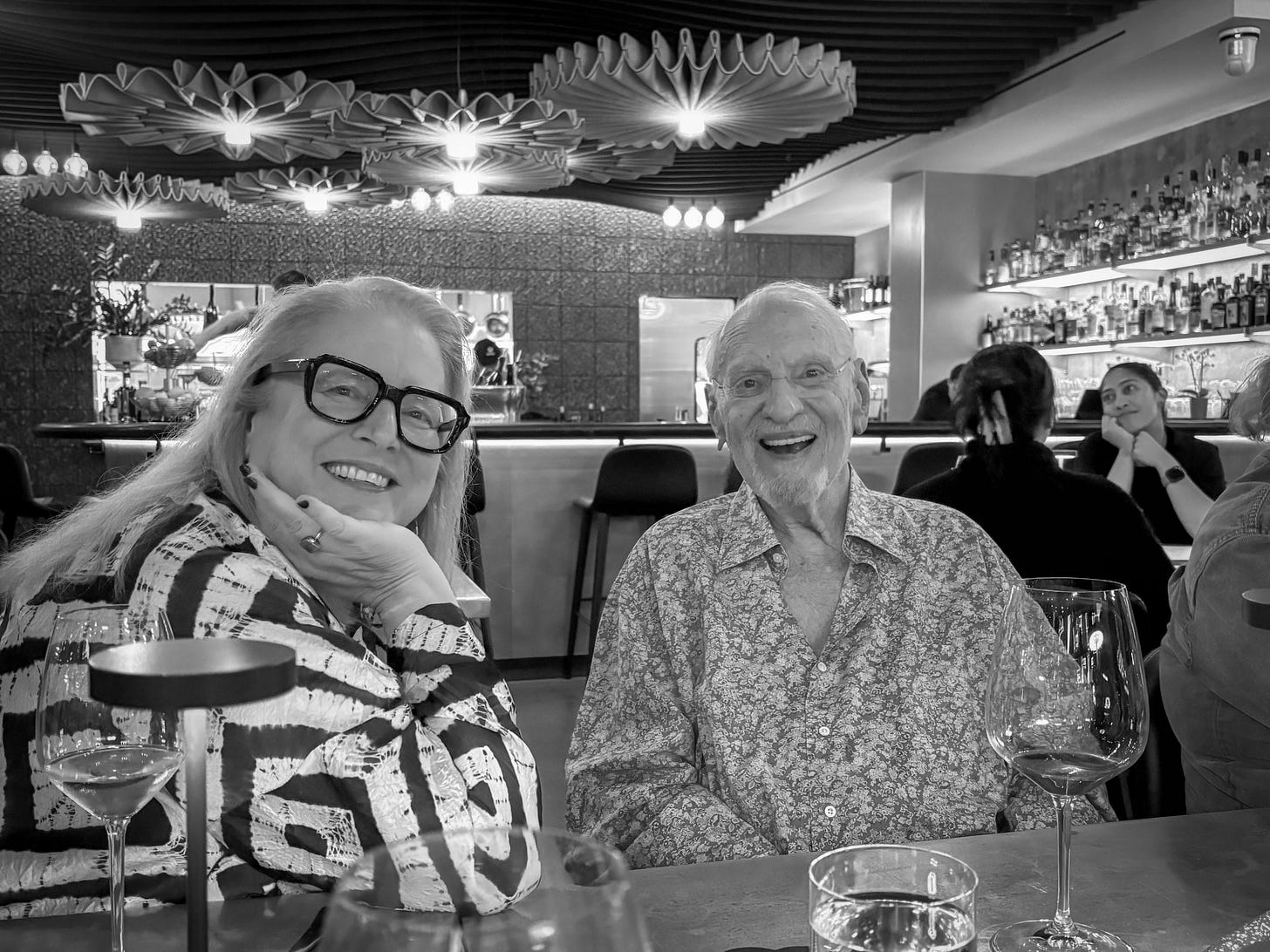

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Carl Khier Doumani, the sharp-tongued iconoclast behind two of Napa Valley’s most idiosyncratic wineries, died peacefully at home on April 22. He was 92.

Born Nov. 15, 1932, in Los Angeles to Peter Khier Doumani and Lillian Abdun-Nur Doumani, Doumani grew up in a family that understood odds. His father was a commodities trader. His mother excelled at cards.

“I was raised as a gambler,” Doumani said in a 2018 interview.

That instinct defined his life — from dropping out of UCLA to buy into a bar to launching restaurants, speculating on land and eventually reshaping Napa Valley’s wine culture.

In 1970, Doumani and his wife, Joanne, bought the dilapidated 400-acre Stags’ Leap estate for $525,000.

“I was just looking for 5 or 10 acres to build a cabin,” he recalled. “Next thing I know, I’m standing on the porch of this boarded-up Victorian manor house saying to my real estate agent, ‘You son of a b--ch,’ and we started to negotiate.”

The house had sat abandoned for years. They moved in and began restoring the property — by hand and with limited funds.

The original plan was to reopen it as an inn, but agricultural zoning shut that down. Instead, they turned to winemaking. Guided by vintner Lee Stewart, Doumani focused on petite sirah and chenin blanc, using century-old vines on the estate.

“We had petite sirah that was planted in the 1940s,” he said. “That was the youngest stuff.”

In our 2018 interview, Doumani shared stories of the estate’s deep winemaking roots that stretched back to the 1890s.

“His passing is a moment for the whole community,” said his daughter, Kayne Doumani. “He was an innovator, an iconoclast and so often a force for good.”

“This place was known as Stags’ Leap since 1890-something,” he said. “They made wine. They sold grapes. Mondavi used to buy grapes from Stags’ Leap.”

That history led to one of the most infamous legal disputes in Napa Valley: the battle over the Stags’ Leap name. In 1972, Warren Winiarski opened Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars nearby. Doumani’s winery bore the nearly identical name Stags’ Leap. The fight over trademarks and AVA naming dragged on for years.

“My attorney didn’t know diddly s--- about trademarks,” Doumani said. “That’s what f-----ed it.”

A judge ultimately ruled that both wineries could use the name, with punctuation separating them: Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars and Stags’ Leap Winery. The AVA? Just “Stags Leap.” The case dragged on for nearly a decade and was once described as “the most expensive apostrophe in California wine history.”

Despite the legal headaches, Stags’ Leap flourished. Doumani delivered his own wine to Bay Area restaurants and built relationships with chefs that helped define a new Napa era. He sold the winery to Beringer (then owned by Nestlé) in 1997 for more than $20 million.

“He didn’t care what anybody else thought—and that was wonderful,” said winemaker Aaron Pott. “He thought petite sirah was better than cabernet and couldn’t understand why everyone didn’t agree.”

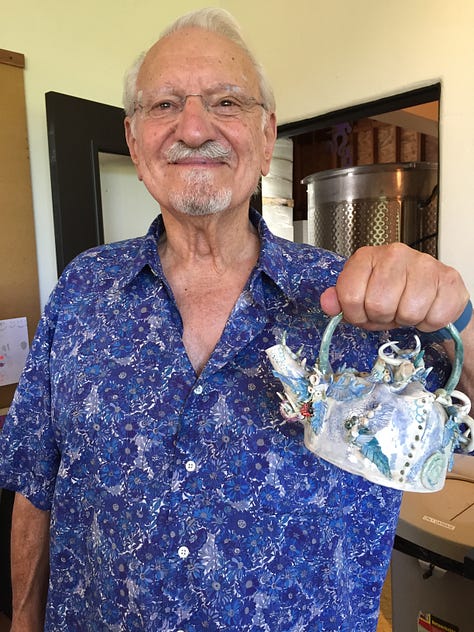

But Doumani’s vision wasn’t finished. Retaining a portion of the estate, he launched Quixote Winery, a surrealist winemaking dream with a building designed by Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser — the only one of its kind in North America. His wines, especially petite sirah, reflected his taste for the offbeat and the bold. He was also an early adopter of screw caps on premium wines.

“I was losing a bottle a case to cork,” he said. “I knew I was right.”

Aaron Pott, who worked with Doumani as consulting winemaker at Quixote, remembered weekly lunches filled with outrageous stories and unwavering opinions.

“He thought petite sirah was way better than cabernet and couldn’t figure out why everyone didn’t agree,” Pott said. “He was his own person — didn’t care what anybody else thought — and he had this incredible personal art collection, pieces bought not for prestige but for connection. He was a character in the very best sense of the word.”

Doumani’s influence often extended beyond winemaking. According to Pott, even Bill Harlan’s path into Napa Valley was shaped by him.

“Bill told me he originally came to Napa to buy a boat from Carl,” Pott said. “But he ended up falling in love with the place and Carl’s lifestyle instead.”

That mix of charisma, boldness and unorthodox charm had a way of pulling people in— and sometimes redirecting their lives.

Doumani’s friendships often defied the formalities of business. Stu Smith, a fellow vintner and member of the infamous GONADS lunch group — short for Gastronomical Order of Nonsensical and Dissipatory Society — remembers Doumani as the reason the club existed in the first place.

“Justin Meyer basically created it so Carl would have someone to eat lunch with after he quit the Vintners,” Smith said. “I probably enjoyed him more than just about anyone in the group. He was sharp, worldly, fun — someone you could love and admire and argue with, all in the same hour. I miss him dearly.”

Doumani’s daughter, Kayne Doumani, described her father as “98% a great guy” but acknowledged his complex nature.

“He could be really hard on people,” she said. “There are folks in the valley who worked for him who might remember that. But his passing is still a moment for the whole community. He was an innovator, an iconoclast and so often a force for good.”

One story she shared captured his blend of spontaneity and generosity. During a City Council debate over public use of a private soccer field in St. Helena, Carl overheard that farmworkers didn’t have anywhere to play.

“So he offered up a piece of land he couldn’t get permitted for and let them build a soccer field there,” she said. “It wasn’t perfect — it wasn’t grass — but it was something. That was just very much my dad.”

In the 1990s, Doumani also became one of the first Americans to import mezcal under the Encantado label — well before the spirit gained traction. His final project — ¿Como No? — was a small vineyard above Quixote that produced limited wine until 2018, when age and Alzheimer’s began to take their toll.

Doumani is survived by his children Lissa (Hiro), Kayne and Jared (Katherine); brothers Michael (Paige) and Peter (Sandy); grandchildren Gianna Lussier (John) and Imogen Doumani; and sister-in-law Carol (Roy). He was predeceased by his parents, his brother Roy, former wife Joanne, daughter Leslie and companion Pam Hunter.

In his later years, Doumani became a quiet philanthropist, supporting Providence Hospice Napa Valley, which helped care for Hunter and later himself. Donations in his memory can be made to give.providence.org/NapaValley/carl-doumani-memorial or by mail to Providence Community Health Foundation, 414 S. Jefferson St., Napa, CA 94559.

Funeral arrangements were private. A celebration of life is planned. More information is available at carldoumani.com.

What a lovely tribute to a man who clearly left his mark on much of the Napa Valley. While loss is always tough, I feel certain that his family, along with many whose lives he touched have endless wonderful stories to share. May his memory be a blessing. What a legacy he has left for us all to treasure. Thank you for sharing this important Napa Valley loss.