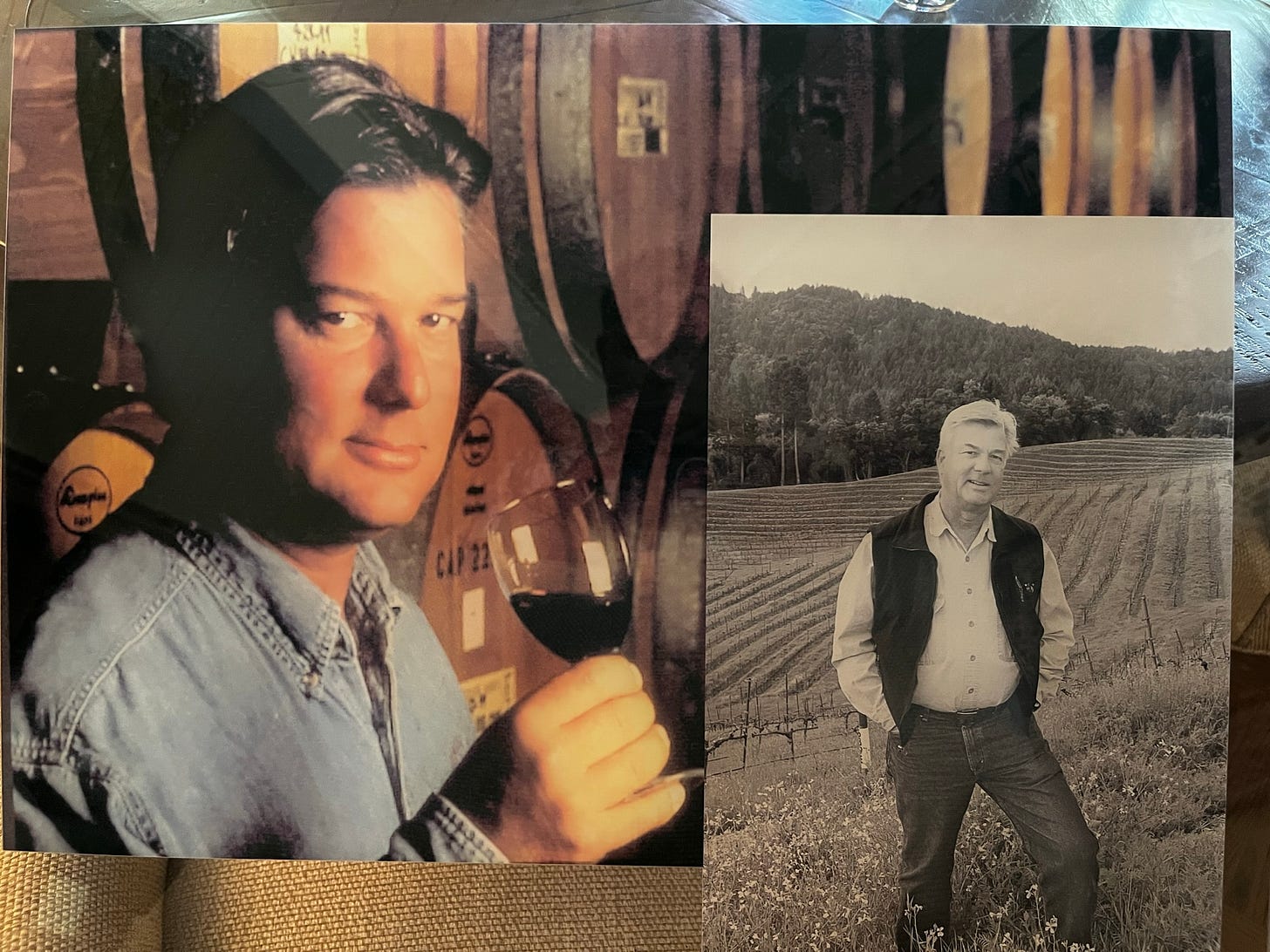

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Earlier this year, after nearly four decades at the helm of Freemark Abbey, Ted Edwards retired from the iconic St. Helena winery. To make way for his replacement before the 2019 harvest, he had stepped back to the position of winemaker emeritus. In February, he made his retirement official.

While it lasted, the emeritus title was a more-than-fitting honor for a vintner whose career spanned much of Napa Valley’s modern era.

Edwards started making wine in the days of an uncongested Highway 29, when fewer wineries dotted the map from Carneros to Calistoga, then watched the valley evolve into one of the world's powerhouse viticultural regions. Along the way, he contributed to Napa’s burgeoning reputation.

Hired out of UC Davis by the storied Freemark Abbey partners in 1980, he was named head winemaker five years later.

“I never knew that I would stay there for as long as I did. But that's just the way it went,” Edwards said in a recent interview, recapping the 40-plus years he spent at the venerable stone winery. “It was an opportunity to work for this pioneering winery in the Napa Valley. It would be my first job, so it was just a fantastic experience to help me to grow and to learn winemaking.”

A succession of acclaimed vintners preceded him, from Jerry Luper and Brad Webb all the way back to Josephine Tychson, the adventurous 19th century founder of a wine estate a few miles north of St. Helena near Lodi Lane.

The early years

Ted Edwards was born in 1955 in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “A great year for Bordeaux,” the vintner noted with a smile, sitting behind his office desk on one of his last days at the Oakville cellars facility next to Cardinale Winery, Freemark’s sister property under Jackson Family Wines. “It was also the same year that Disneyland started,” he laughed. “Those are my two claims to fame.”

His reference to Bordeaux was one of several that peppered the conversation: as the category of wine grapes that helped determine the arc of his career; and for the great cabernet and merlot region of France that has long influenced the California valley where that four-decade career — his true claim to fame — played out.

From his college years up to the present, Edwards’ world has mostly been defined by his relationship to grapevines and wines. But it really started with apples.

He spent his childhood in western Colorado, where his parents owned a 44-acre ranch and farmed apples and alfalfa. But back-to-back years of frozen crops caused his father, a part-time teacher, to re-think farming for a living. So the elder Edwards sold the property and moved the family to his wife’s home state of California. He found a high school teaching job in Orange County, where they lived until his son got to the eighth grade, “and then we headed up to Northern California and bought a house in Sebastopol,” Edwards said. “My mom always loved this area.”

Though he hadn’t yet finished middle school, the move to Sonoma County would prove instrumental to his eventual career.

As a high schooler in the early 70s, he developed an interest in the life sciences, biology in particular. It took him to junior college in Santa Rosa and then UC Davis, where he majored in biochemistry. He landed a job after graduation with a Davis professor of plant physiology — fittingly, Edwards assisted on biochemical research into alfalfa — and married his high school sweetheart.

“So I was working at Davis and thinking, ‘What's my next step?’ I was going to do graduate work, for sure, but in what? And my undergraduate degree lent itself well to winemaking and enology. It was almost like a no-brainer.”

He also considered a doctorate in biochemistry and a teaching career. But wine exerted its pull, and in a way that might have seemed unusual — though, in retrospect, not to Edwards.

“Since eighth grade in Sebastopol, I was basically from the wine country,” he said. “I'd tag along with my folks when they would go visit wineries. Of course, I couldn't taste wine with them.”

He circled back to his childhood in Colorado and to the apples his parents grew on the ranch. They sold most of the fruit but kept a small amount for themselves, which they stored underground in a neighbor’s orchard. Some they took to a community facility with an old basket-press to make apple juice and cider, using pillowcases to filter the freezing cold liquid. “That was my first hands-on pressing fruit and filtering! I would have been about nine or ten years old,” Edwards wrote in a separate email. “It was really cold work!”

But he loved the associated aromas, recalling vividly in his office “the smell of apples, basically aging in a subterranean environment. You had that apple smell and also the smell of earth, because you were in a cave, really.” Connecting the dots from Colorado to Sebastopol, he described walking into wineries with his parents as a teenager, the cellars redolent with “that really intense smell of aging fruit, and the earth smell the winery would have.”

“In essence, the apples were decaying very slowly. And a winery is where grapes have decayed into another food product, you know? You get those interesting smells, and I really loved that.”

“And,” he emphasized, “I loved visiting wineries.”

Later, as a young post-graduate, he was — unsurprisingly — drawn to wine. The first UC Davis professor he consulted in the school’s Department of Enology and Viticulture told him he had a perfect background for winemaking. Little could the professor have known how strongly that background was tied to some deep, olfactory memories, or the role they played in bringing him to Davis’ viticultural doorstep.

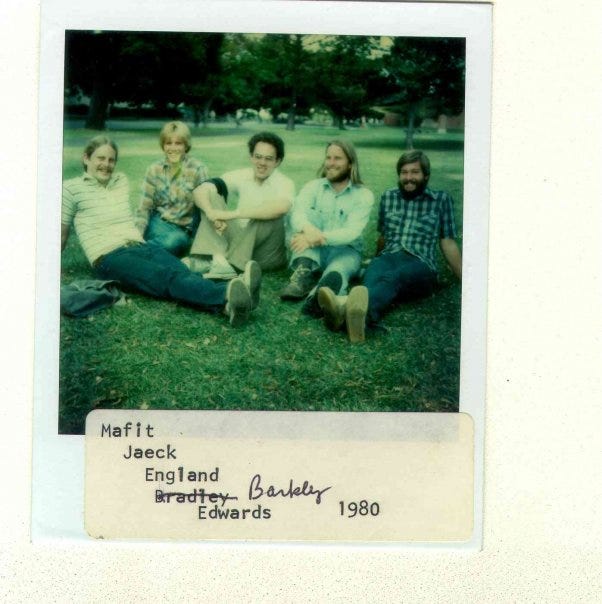

Edwards entered the Davis master’s program and, diploma-in-hand in the summer of 1980, shifted his attention to employment listings at the viticulture department. He saw one posted for an assistant winemaker at Freemark Abbey. While he hadn’t heard of it, a little digging clued him into what he called a “buzz” around this Napa Valley winery. There was a good reason for it.

“When I mentioned the job to my professor I worked for in the lab, he said, ‘Freemark? Oh yeah, I know that winery.’ Then I mentioned it to some friends, and that's where it came out that its reputation was significant,”— thanks, in no small part, to Freemark’s inclusion in the Judgment of Paris tasting in May of 1976 and a short but impactful Time Magazine article about it two weeks later. American wine drinkers would soon get acquainted with labels like Chateau Montelena, Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, and Freemark Abbey: lesser-known brands that showed up in Paris that eventful spring and helped change the course for California wine.

Edwards secured a job interview with two of the managing partners at Freemark, Brad Webb and Chuck Carpy. They offered him the assistant winemaker position under Larry Langbehn, who succeeded Jerry Luper, the highly respected vintner with a hand in Freemark’s Napa Valley chardonnay and cabernet included in the Paris tasting.

While at Davis, Edwards worked as a teaching assistant under Dinsmoor “Dinny” Webb, the brother of Brad Webb, but was unaware of a further link between the school and his soon-to-be employers until he got hired: in the early 70s, the Webbs established a yearly pipeline of Davis viticulture students to come work harvests in St. Helena. They called it “The University of Freemark.” Edwards laughed and remembered that Langbehn referred to the arrangement as “Davis Rent-a-Kid.” Either way, many future winemakers passed through the winery’s cellar, a program Edwards continued. “We would do that every year. I would look at Davis to get an intern for harvest,” he said. “It was great, and it kept me fresh too. But that's another story.”

Building a career

For Ted Edwards, the story really began to unfold a few years after he signed on with Webb and Carpy during Napa Valley’s great vintage of 1985. That was when he saw his career start to turn a corner. Of course, plenty had occurred at Freemark Abbey before then to set the stage.

The winery takes its churchly sounding name from a combination of the names of three earlier partners, including Albert “Abbey” Ahern, a Southern California businessman who led the purchase of Lombarda Cellars from the Forni family in 1940. Fairly successful wines were produced in the old stone cellar until Ahern’s death in 1959, then it operated as a roadside restaurant and candle shop for several years.

“The lights at Freemark Abbey came back on in 1967 when a partnership headed by Charles Carpy bought the old Lombarda place,” the historian Sullivan wrote in Napa Wine. “So dim was the memory of the Ahern and earlier Forni operations that…Carpy wondered at first what kind of religious institution had been housed here.”

Brad Webb was the partners’ first head winemaker, then he and Carpy hired Jerry Luper in 1969. The Fresno State graduate carved out his own place in Freemark Abbey history from the early 70s right up to the Judgment of Paris.

Larry Langbehn took over in the summer of 1976 when, soon after the Paris tasting, Luper, his wife, and their young family left Napa Valley for a European sabbatical. Unknowingly on deck was a future UC Davis master’s candidate.

Edwards smiled over the awkward memory of heading out to Napa Valley four years later with a fellow graduate to interview for the same job at Freemark Abbey. “I got the job, fortunately,” he laughed.

“I remember I was interviewing with [the partners]. Then Larry brought me back later for a little informal thing, and Chuck asked, ‘Why do you want to work here?’ And I said, ‘Well, this is close to home.’ I told him that my grandma lived in Yountville, and I had an aunt that lived in Yountville. So we just kind of clicked.”

In the summer of 1980, Edwards moved from Davis to Napa and started his first winery job.

Just a couple of vintages into it, he got acquainted with Phil Baxter, the winemaker at Rutherford Hill Winery, and was recruited to become his assistant at the larger operation. Conveniently, Freemark and Rutherford Hill were sister properties and shared a number of investor-partners, including Carpy and Bill Jaeger. It facilitated Edwards’ short move across the valley, which lasted three years.

Leading up to the ’85 harvest, those partners had their hands full at each winery. Langbehn was planning to start his own winemaking project, and Baxter had departed that spring for the same reason. Edwards recounted that the partners “were kind of in limbo on what to do.” Jaeger wanted a change of direction in St. Helena. “So they called me up and had me come in and said, ‘We want to offer you the job at Freemark Abbey.’”

Langbehn, he noted, stayed through the ’85 harvest — an epic vintage, as it turned out, and one thing in hindsight the Freemark-Rutherford Hill owners did not have to worry about—“but the problem was that we had no head winemaker for that harvest at Rutherford Hill. So I needed to stay there. It was kind of like I had one foot at Freemark and one foot back at Rutherford Hill.”

At the close of that memorable harvest, a new stage was set for Edwards, and one foot became two firmly planted at the old St. Helena winery for the next three and a half decades.

“By the first of the year in 1986, I was officially the winemaker at Freemark Abbey,” he said. “And I was happy as a clam because now I had downsized to a really comfortable, fun-sized winery. The production was around 25,000 cases at that time. It was just fun, fun, fun.”

With more amusement in his voice, he described the mid-80s scene at Freemark: “In the first year or two, there were actually only about three of us that ran the whole production facility. I was the winemaker. I would write all the work orders, do all the analysis, work harvest, call all the shots, and then”— he paused to laugh again — "clean up at night. It was really fun. We would hire, like I said, a Davis Rent-a-Kid. We would always have an intern who would help, and so that worked well.”

Over many vintages, including those impacted by the phylloxera virus of the late 80s and early 90s, Edwards incorporated grapes from a variety of sites around Napa Valley and its sub-AVAs. But in terms of importance, nearly all were second to the Rutherford AVA, which formed the backbone of Freemark’s wines.

A detailed Rutherford vineyards map hung on the wall, one of the few decorations left in his soon-to-be-vacated Oakville office. “The Carpy family owned about 80 acres. And there was Wood Ranch, which [partner] Laurie Wood owned. These were contiguous,” he said, indicating a large swath of property running from Conn Creek Road to the Napa River. “And we owned Red Barn Ranch nearby, which was 145 acres. So we farmed all that and took most of Red Barn's fruit.”

He then pointed to a pair of Rutherford vineyards sitting to the west of Highway 29: one slightly north and adjacent to both Inglenook and Georges de Latour; the other just south of Bella Oaks Lane, a stone’s throw from the Oakville AVA border. These were, respectively, the Bosché and Sycamore Vineyards — place names synonymous since the 1970s and 80s with Freemark Abbey cabernets. Along with Red Barn, Carpy-Connolly and Wood Ranches, they comprised what he called a “quadrant” of vineyard sites that were intrinsic to his career. “When you look at my history, most of it has been walking these Rutherford vineyards.”

The time Edwards invested among the vines proved to be one of the keys to Freemark’s success as a wine brand. Putting his viticultural training into practice, he saw his efforts dovetail with an important transitional period in Napa Valley. “The growth that we witnessed and demand from the public was for red Bordeaux varieties,” he explained. “We could make more money — and this, I think, was true for most of the Napa Valley — with reds like merlot and cabernet than with chardonnay and pinot noir, which we had planted in Rutherford, too. So we pulled out all of that stuff and replanted with the Bordeaux varieties.”

Edwards described several grape-growing developments of the period, including a switch to new and more phylloxera-resistant root stocks, the careful, vertical positioning of vine shoots for improved photosynthesis, and adoption of modern-day trellis systems. “Before that, we didn't really do it,” he said. “So in the 80s we brought in some new strategies and grape varieties planted in the right places. A lot of that continued into the 90s. And I was a part of all of it.”

“They were very interesting times. There was a lot of growth in the winery and in our vineyards,” he said. A prime example was his role in the development of Sycamore Vineyard as one of Freemark’s signature cabernet bottlings.

“First in 14 Years: A New Wine From Freemark Abbey,” proclaimed a Los Angeles Times headline above a story from October 1988, reported by Dan Berger. “The 1984 Freemark Abbey Sycamore Vineyards Cabernet ($20) is very ripe and supple with forward cherry and chocolate flavors, an attractive fruity aftertaste and ample tannin,” he wrote in his short piece.

Berger, the now-veteran wine country journalist, also mentioned that Freemark’s Bosché Vineyard cabernet, which debuted in 1970, was its only previous vineyard-designated wine. The Ted Edwards of that time was a young high school student. Just a decade later and less than a year out of UC Davis, he found himself deciding, alongside Langbehn and Carpy, that Sycamore Vineyard was a special piece of Rutherford real estate.

The vines planted in the mid-70s by owner John Bryan had started to produce small quantities of promising cabernet sauvignon grapes by 1980. “We were all excited about Sycamore because we had one gondola—just four tons, with very small berries and lots of flavor,” Edwards recalled about that year’s harvest. “John Bryan, who was one of the partners, and Chuck and everybody wanted to make another vineyard-designated cabernet, but one from Sycamore Vineyard. So that was one of the things I was in charge of.”

He would take charge of many more in the coming years. In 1992, Carpy and the other six partners offered him an opportunity to join their ranks. So he invested some of his own money in the winery and, at age 37, became its eighth partner.

His legacy

A year after Ted Edwards assumed an ownership role at Freemark Abbey, Chuck Carpy was interviewed by historian Carole Hicke as part of UC Berkeley’s “California Winemen Oral History Series” and made an observation about his newly minted partner. “We have a very good, competent winemaker who could operate this place on a day-to-day basis without any problem at all from now on if we had to,” he told Hicke.

It was fitting, then, that Edwards assumed a leading role when Carpy died unexpectedly in 1996. He teamed up with Carpy’s daughter, Catherine, who began working on the sales side at Freemark in the early 90s.

“I was basically the managing partner and was in charge of production, and Catherine was in charge of marketing and sales. And that's how we kind of divvied it up. And we actually did quite well,” he said. “The late 90s was a great time to be in the wine business. The winery was really turning good profits for the partners, and there were some good vintages. It was just a lot of fun.”

Now wearing multiple hats, Edwards never strayed far from the Rutherford vineyards that remained integral to his role as head winemaker.

In a 2020 interview, he confessed during a walk-through of Sycamore Vineyard that it had been a few years since he’d tasted that ’84 cabernet reviewed by Dan Berger. “I'm sure it's probably doing great” he said at the time. “We actually saved quite a bit of that wine, because it was the first vintage.” He instead shared a recent memory of sampling the ’87 Sycamore, another in a string of great 1980s cabernets he produced.

Most opportunities to pull the corks of these older wines came courtesy of Freemark Abbey’s extensive library of vintages, which the partners started stashing away in the 70s. To this day, the rarest include early Bosché Vineyard cabernets vinified by Jerry Luper and Brad Webb.

Back in his office, he explained that the library was created “to have some older wines available for restaurants that could take advantage of this program,” though it soon became popular with consumers and winery visitors. “So in today's world, let's say somebody was born in 1975. They could ring up the winery, and we could most likely supply them with a bottle from that year. And that's all thanks to the partners starting the program. It was probably the largest wine library in Napa Valley.”

If its status as one of California’s most historic wineries was what caught the attention of the wine entrepreneur Jess Jackson and his wife and business partner, Barbara Banke, the library was surely the icing on the cake when they purchased Freemark Abbey in 2006.

Edwards recounted that, while somewhat informal in the 70s and 80s, the partners’ business plan to start a wine library was well-conceived. “What's interesting is the Jacksons have really embraced it,” he added. “And I think they're holding back even more than what the original partners did, which is great.”

Under the new Jackson Family Wines ownership, he continued to run the production out of Freemark Abbey and, because of the growth of the cabernet and merlot programs in the leadup years, at a larger custom crush facility in south Napa. JFW soon had Edwards and his team move all of the winemaking to the Oakville cellars winery, where the equipment was first-rate and space was plentiful. The 2008 vintage, he said, was the last crushed at Freemark.

It was the end of an era in St. Helena. The stately stone winery, appearing no different from the outside, became what is today a marquee hospitality center and a showcase home for the growing wine library.

He continued, “Since then, they’ve made even more improvements, adding better grape-sorting capabilities and that sort of thing. And Kristy just told me she's going to get an optical sorter this harvest, which is a really nice piece of equipment. So she's taken it up a level.”

Edwards was referring to Kristy Melton, his fellow UC Davis alum who was a young but already experienced winemaker when she came on board at Freemark in 2018 as his assistant. The following year, she was named head winemaker and worked alongside him during the three emeritus years. Acknowledging four decades worth of pride in the brand and its wines, he displayed obvious pleasure having Melton as his successor.

“Kristy’s just doing a stellar job. She’s very intelligent, has a talented palate, and she's a good thinker on her feet. It's a very comfortable feeling for me to have her in place. I couldn't be more happy.”

Melton was put to the test immediately. To help acclimate her in 2018, Edwards handed over responsibility for the winery’s chardonnay production, a signature Freemark white wine going back to the Webb-Luper days that she quickly adjusted to fit her own winemaking style.

“It makes all the sense in the world that Ted would pass the winemaking mantle on to her,” Gilian Handelman shared in a recent email. The vice president of education at JFW was Edwards’ colleague for many years. She remains a keen observer of winemaking personalities across the breadth of the company’s large portfolio.

“There’s a big-heartedness in Kristy’s bones,” Handelman wrote. “She will carry on the winery’s point of view with the same sensibility. She’s as stubbornly adherent to craft as Ted, and I’m quite certain that’s why he chose her.”

“I think you can regard Ted as being the perfect guy to take on the legacy and carry it forward,” Freemark Abbey’s longtime brand ambassador Barry Dodds said of his now-former colleague over the phone in September. “He wasn't looking at making himself wealthier, wasn't pounding his chest to make sure he got the next rockstar winemaker job in Napa Valley. The way he went to work was saying, ‘This is what I'm responsible for.’ Ted showed up on a daily basis with 100% loyalty and passion for Freemark Abbey.”

The JFW acquisition in 2006 was preceded five years earlier by a sale of the winery to a different group, Legacy Estates. Edwards stayed on as the director of winemaking and, in that deal, arranged a 1031 exchange of his share of ownership for a commercial property in Napa. “It keeps me busy,” he said of the 1920s converted office building, a Craftsman showpiece in downtown Napa. “There’s always something to do.”

Retirement at 67 is Edwards’ reward for the loyalty and passion Dodds spoke of. The next phase for him and his wife, Jennifer, might hold some surprises, but he has a plan that includes 2024 travel to Tuscany and northern Italy, continued involvement with Freemark Abbey in various vineyard and tasting projects, and “a cabin in Tahoe that is calling.” Spending time with their five grandchildren also figures into the plan.

“It’s a great experience where I can create my own agenda for the day,” he wrote in an email over the summer. “I have dreams where I'm in the heat of harvest trying to figure out some decisions about what to pick. The dreams are an interesting aspect. I'm just glad I’m not running a bottling line in them!”

For the foreseeable future, that waking reality will be addressed by Kristy Melton, along with myriad other responsibilities. She can take Edwards’ accomplishments as her example.

“It's mind-blowing, the amount of change that's happened in the last 40 years,” Melton said on a recent call while gearing up for the ’23 harvest, already her sixth at Freemark. “To ride all of the changes in winemaking, it requires determination, ingenuity and a certain calmness and sense of patience. I think that's something I try to teach younger winemakers: we're in this for a long time.”

She recognized in her former boss a long-term vision, along with an overall demeanor that reflected professionalism and industry insight. “Those skills,” she noted, “have helped him deal with everything, whether it's Mother Nature, ownerships or technology. There are changes that abound every year in this industry.”

When Chuck Carpy and his six partners purchased the St. Helena winery in 1967, stirrings of change were already in the air in Napa Valley. Writing in Napa Wine about several new winery enterprises that launched during that decade, Charles Sullivan listed, among others, Chateau Montelena, Heitz Cellar, Chappellet and “a revived Freemark Abbey.” The late wine historian described them as names that “march across the page like hussars, leading the charge, in the vanguard of the great wine revolution of the sixties and seventies.” Now entering retirement after one of California’s longest winemaking careers, Ted Edwards is a living link to that revolutionary period.

“Brad Webb, Jerry Luper, and myself, we had some innovations in making the Freemark Abbey wines,” he shared recently. “We never did stand still. You know, we were always looking to improve our vineyards. We had a lot of work to do in them, and we still do. So Freemark has staying power, and I think it will always have this reputation and legacy. I would love to see that continue on into the future.”

“We're so lucky to have this jewel called the Napa Valley,” Edwards added, laughing again. “I mean, it's a Garden of Eden where you can grow anything. I think we're fortunate that we settled on grapes.”

Tony Poer is a Napa Valley-based writer.