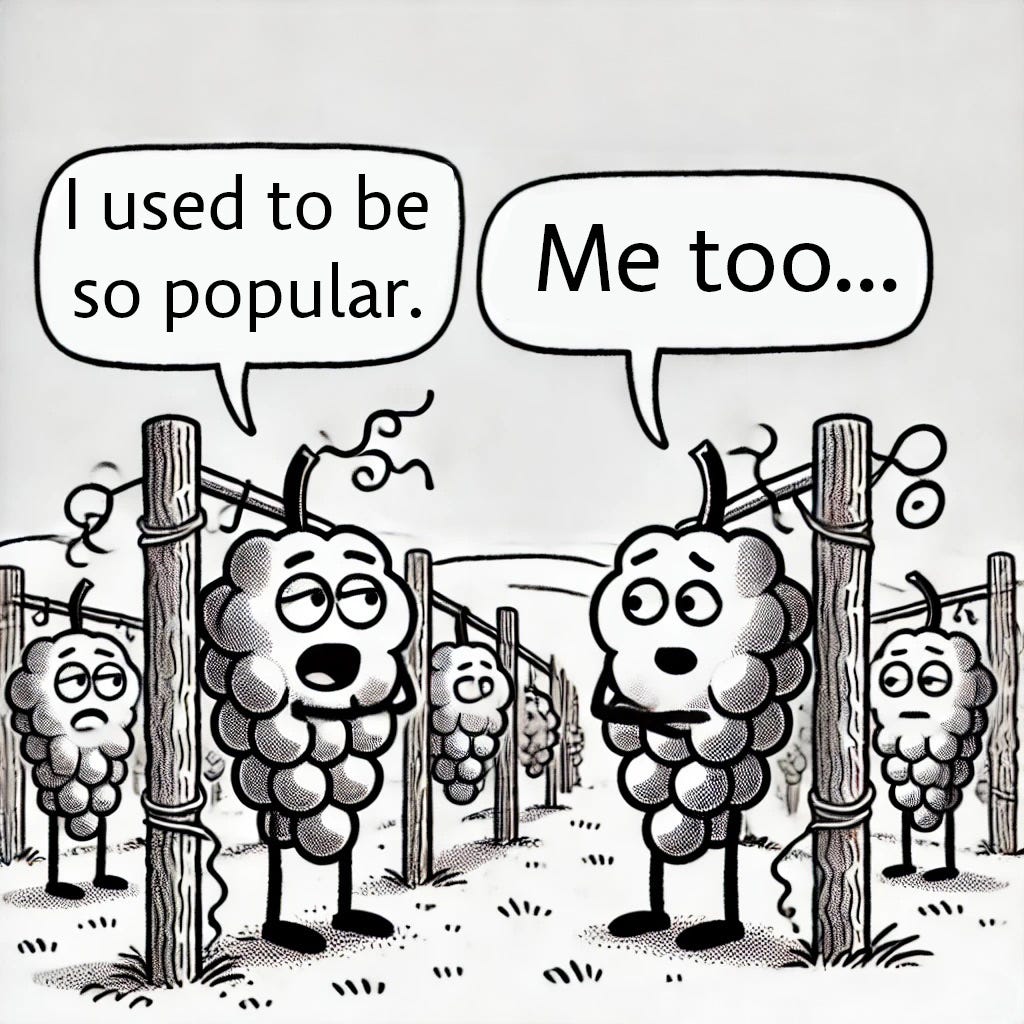

NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — Wine sales throughout the country are stagnant. Retail wine stores and restaurants nationally are closing. Alcoholic beverage consumers, who are offered infinitely more beverage choices than ever, are turning their backs on traditional wines, which I define as dry. The downturn is hurting the entire wine industry, which today faces serious problems.

One large Sonoma County wine company is strongly rumored to have acquired a massive quantity of bulk wine for 52 cents per gallon. An Anderson Valley winemaker told me this past week that pinot noir grapes from his prestigious district that would normally sell for $8,000 per ton or more are going for $1,000 per ton – and there are no takers for the majority of the fruit.

Several grape-growers with whom I have spoken estimate that approximately 20% of all the grapes grown in the Napa Valley and Sonoma County this year will simply not be harvested. Grape sales are flat, and some contracts have been abandoned. (One rumor said that the 20% figure probably is closer to 30%.) I have heard of some vineyard owners offering to give their grapes away if the taker pays the picking costs.

One Sonoma County winemaker told me that he will make only small amounts of his vineyard-designated wines and little else: “We having enough wine from previous vintages.”

Moreover, dining out has become a luxury for many people. This means a decline in restaurant wine sales. A headline last week in The Los Angeles Times read, “More than 75 big-deal L.A. restaurants closed so far this year.” This follows an article last Dec. 22, also in the Times, that said 65 major restaurants closed their doors in 2023.

One of Santa Rosa’s best cafés, Vine Burgers, closed in late August, a victim of patrons trying to save money. Owner James Byus said dining out has become a special occasion for many diners. And in spite of excellent reviews, his restaurant couldn’t survive the dining downturn.

If more proof were necessary that everyone is having a hard time selling wine, forget inflation; let’s talk about deflation. An article two years ago in The New York Post noted that restaurants are charging about the same for a glass of wine, but pouring sizes are shrinking. A line in that story: “Diners say they’re increasingly being served paltry pours, and industry insiders confirm their suspicions.”

The story said that in the last few years, a standard wine serving in some restaurants, which years ago was 6 ounces, has shrunk to 4 ounces. The Post story also noted that many diners have noticed this trend toward smaller pours.

(Thirty years ago I wrote that diners buying a glass of sparkling wine in a restaurant almost never get 5 ounces. Standard champagne flutes used at many restaurants are designed to carry no more than 5 ounces even if the pour is right to the rim. And little has changed. Champagne by the glass is frequently a rip-off.)

Meanwhile, I have observed an interesting phenomenon recently: Corkage charges at many restaurants have gone sky-high. Before COVID-19 invaded the world, café corkage charges ran between $10 and $15 per bottle. In the last six months I’ve seen corkage charges rise to $25 and more. Many cafés now charge $40. Even well-heeled diners say they think this is outrageous.

There are several reasons why there is such austerity in the area of wine sales, some of which can be attributed to a virulent neo-Prohibitionist movement that claims, without proof, that any alcohol at all is detrimental to human beings. (See below for a related article.)

Shortages and surpluses have existed in the California wine business on and off for decades. This is, after all, a business of agriculture, and wine is susceptible to all kinds of vagaries delivered haphazardly by Mother Nature. Over the last few years especially, heat waves and wildfires have caused shortages in some wines. And bumper crops have created surpluses.

However, few wine critics or wine writers ever attempt to separate Commonplace Wine (CW) from Fine Wine (FW). And they are differentiated from liquids that I call Wine Impersonators (WI). These definitions are clearly arbitrary and might be considered disrespectful to some of their producers. I am more than happy to debate people who make these products.

I think it could fairly be stated that a wine called Stella Rosa, one of the most popular wines sold in the United States today, is a WI. It’s an imposter because almost all of it is sweet and flavored. The fact that it is technically a wine does not prevent it from being in a category that might be determined to be a “winelike soft drink.” It’s not just slightly sweet; it’s cloying, so it does not appeal to people who drink either FW or CW wines.

(As an example of a CW, think of Two-Buck Chuck, which actually is more expensive than two bucks.)

I can imagine that almost all of the flavored wines are selling to people who really do not consider themselves to be wine-drinkers or even like traditional table wine.

Other WI wines include products that are flavored, such as with pineapple juice, peach flavoring or even wines that are supposedly aged in whiskey casks, a particularly abominable concept. (I have a theory that wine that was tainted with smoke from a fire ended up being marketed as a whiskey cask-aged wine.)

One recent example of a flavored wine is a chardonnay that was theoretically “enhanced” with a pumpkin spice flavoring. Cupcake has an entire line of lower-alcohol wines that are flavored with things such as raspberry, nectarine, peach and honeydew melon.

There is no pretense here that this is either FW or even CW. In a conscious effort, this is pop wine. And then there are the real imposters. They were made to look like fine wine and their prices indicate that they are, but they clearly are not.

I am not enamored of a wine called Meiomi, which may illustrate one reason why wine sales in the United States are under so much pressure these days. Is this really wine in the traditional sense? It is popular, but are the people who buy it really wine-drinkers?

It is rarely discussed by wine writers, who spend most of their waking hours trying to figure out how many points to bestow on a chardonnay or a cabernet. But a far more important issue is how vast are the numbers of Americans who are drinking sweet imposter wines. The market for this stuff is huge – and that probably is the main reason that huge Constellation Brands was willing to spend a reported $315 million to buy the Meiomi brand nearly a decade ago from Napan Joe Wagner.

In his Fermentation newsletter recently, wine observer Tom Wark began, “The gap between the attitudes of the elite and those of the plebes is never so wide as it is with wine and movies,” adding, “The wine elite HATE Meiomi, that succulent, flat, wildly fruity, oaky and easy-to-drink rendition of pinot noir.”

(Meiomi also makes several other wines under that label.)

Later, Wark writes, “…the wine-drinking public LOVES this wine in a way that infuriates the somms (sommeliers), wine critics, wine retail specialists and wine educators. How in the world could consumers embrace such a plumped-up, oak- and sugar-driven, artificial, lab-created head-fake toward ‘real’ pinot noir?”

His observation is accurate in describing how folks inside the wine industry dislike the concept of sweet, characterless red wine selling for $20 or more throughout the republic. However, to me, this is nothing more than a reminder that the United States is not and never has been a wine-drinking culture. A real wine-lover would never buy this stuff.

Most of the wine sold in the United States is either actually sweet or very soft, usually because of low acidity. As previously stated, this is pop wine and has nothing to do with CW or FW. To me, Meiomi is a WI. Any connection to fine wine is purely imitative. Fine table wines are dry and should have some reflection of place.

Which then, unfortunately, leads us back to what’s wrong with the California fine-wine industry and its major problem – extremely slow sales. If the majority of supposedly fine red wines in this country are all made to be homogenously dark, concentrated, oak-flavored, soft, slightly (or actually) sweet and have absolutely no sense of place, are we not taking a page out of the Meiomi playbook?

Some of the cabernets I taste these days are nearly as sweet as the impersonators. Not only do they not taste like cabernet, but they do not have sufficient structure to work with a typical savory dinner.

I was speaking with a longtime Napa Valley winemaker the other day. He was disrespectful of roughly 95% of Napa Valley cabernets today. He said they are so high in alcohol that he can’t consider putting one in his mouth.

“You know,” he said, “in a way, these wines have nothing to do with cabernet.”

He added, “We have all read about slow sales. Well, one reason may be that the American consumer is just getting tired of the alcohol.”

He suggested that producers of high-quality chocolates probably are doing a huge business these days because today’s cabernets work best not with food but with chocolate.

As a contrast to slow retail and restaurant sales of fine wine throughout the United States, I have anecdotally heard that direct sales to consumers from fine-wine websites are rising.

Dave Parker of Benchmark Wine Group told me that his site recently has been on a roll.

“Perhaps we’re bucking the trend, but [the second quarter of 2024] was the best sales quarter in the history of the companies. We had our best July ever, and these first nine days of September are setting a record. Overall auction prices have been moving up in fits and starts since the beginning of 2024 and steadily since July 1. Along with challenges are opportunities, as has always been the case in the wine business.”

Benchmark recently acquired the personal wine cellar of the late controversial pioneering winemaker Sean Thackrey, whose unconventional techniques produced some of the state’s most fascinating wines. Made from grapes grown in Napa, Marin and Mendocino counties, Thackrey’s portfolio goes back decades. Parker says every wine in the collection was perfectly stored and is in excellent condition.

Benchmark is offering the Thackrey cellar on its website.

Berger’s Wine Discovery of the Week

2021 Trefethen Merlot, Oak Knoll ($50) – Three decades ago it was not difficult to find red wines from the Napa Valley that were structured to go with food. In the last 25 years or so the fashionable wine was a cabernet that was made to be approachable, often sacrificing food compatibility and age-worthiness. Then two decades ago, the film “Sideways” caused a severe consumer backlash against merlot. However, the variety never disappeared, and those who had it planted in blessed locations continued to make wines of excellence from it. This wine is an exemplary example, with a classic Napa Valley aroma that retains its historic persona with hints of dried herbs such as wild thyme and savory. The fruit is black cherry with a hint of pomegranate. The near-perfect balance (less than 14% alcohol) delivers flavors that do not require excessive aging to access. The family’s website notes, “Rich aromas of plum and red cherry are softened by notes of lavender and sweet spices. On the palate, silky tannins carry the red fruit, leading to a lengthy and elegant finish.” The wine is young; I found it best 24 hours after pulling the cork. But it is structured to age for at least 15 to 20 years. The balance is impeccable. Part of the reason it is so reliable is that it comes from Oak Knoll, a district underrated for its ability to make sensational, balanced wines. The merlot is occasionally seen discounted to about $40.

If today’s story captured your interest, explore these related articles:

Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: Proof That Napa’s Older Cabs Can Age

Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: Napa and Sonoma as True Vinous Siblings

Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: The Nostalgia and Nonsense of Barrel Tastings

Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: The Evolution and Art of Winemaking

Dan Berger’s Wine Chronicles: How Wine Is Packaged Can Affect Its Quality

Dan Berger has been writing about wine since 1975.

The views, opinions and data presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy, position or perspective of Napa Valley Features or its editorial team. Any content provided by our authors is their own and is not intended to malign any group, organization, company or individual.