NAPA VALLEY, Calif. — For the past five years, the Land Trust of Napa County has increased its efforts to battle climate change by creating a large wildlife corridor, piece by piece.

Earlier this year the Black Sears family donated 117 acres of pristine forest land on the top of Howell Mountain to the LTNC. It is adjacent to the land trust’s 3,030-acre Dunn-Wildlake Preserve and is in a key location to help the land trust create a continuous corridor of protected land for wildlife along the ridge on the eastern side of Napa Valley, said Doug Parker, Land Trust of Napa County’s president and CEO.

“Everybody knows that animals, especially larger mammals, have large ranges and they move across the landscape,” Parker said. (As do smaller animals, and over time plants also migrate.) “There’s already a lot of evidence that lots of plants and animals in the Northern Hemisphere are moving north in response to hotter temperatures.”

If you protect land, as the LTNC does, Parker said it is critical to connect that property to other protected lands to provide that wildlife corridor.

“The whole idea is to make all the natural values of Napa more resilient to the changes that climate change has already started creating and will continue to create going forward,” he added.

Currently the corridor goes from the 7,260 acres at Robert Louis Stevenson State Park on the top of Mount St. Helena to the Dunn-Wildlake Preserve to forested land in Angwin, protected in partnership with Pacific Union College, to Las Posadas State Forest. Then the corridor extends past Lake Hennessey, which is a major source of water for the city of Napa. Currently there is a gap between the Dunn-Wildlake Preserve to the 800 plus acres of forested land owned by Pacific Union College in Angwin.

Once the Napa corridor extends to Lake Berryessa, it could easily connect to a large wildlife corridor made up of four contiguous national forests, comprising 7 million acres of protected land that runs all the way to the Oregon border. If the local corridor can reach that large corridor, then Parker said, “We can be a lot more confident that everything we’re protecting actually will have a better chance to survive over the long term.”

Parker estimates it could take another five to 10 years to fill in the gaps in the local wildlife corridor.

Black Sears donation

It seems only natural that the Black Sears family donated 117 acres of pristine forest land on the top of Howell Mountain to the Land Trust of Napa County. For years the family has had a special beautiful place on the property called “The Point,” which they cherished and which has a tremendous view north from the property, Parker said.

“As we’ve seen the valley change so much in terms of development, it became apparent that we wanted to ensure the permanent protection of the place that we love so dearly,” said Ashley Sears Jambois, the daughter of Jerre Sears and Joyce Black. “Gifting this piece of land to the land trust feels like the best way to pass on the torch of stewardship.”

Joyce Black Sears said the donation “honors the land and Harry Tranmer for his foresight as a founder of the Land Trust of Napa County. May nature thrive on this beloved land in the care and protection of the land trust in perpetuity.”

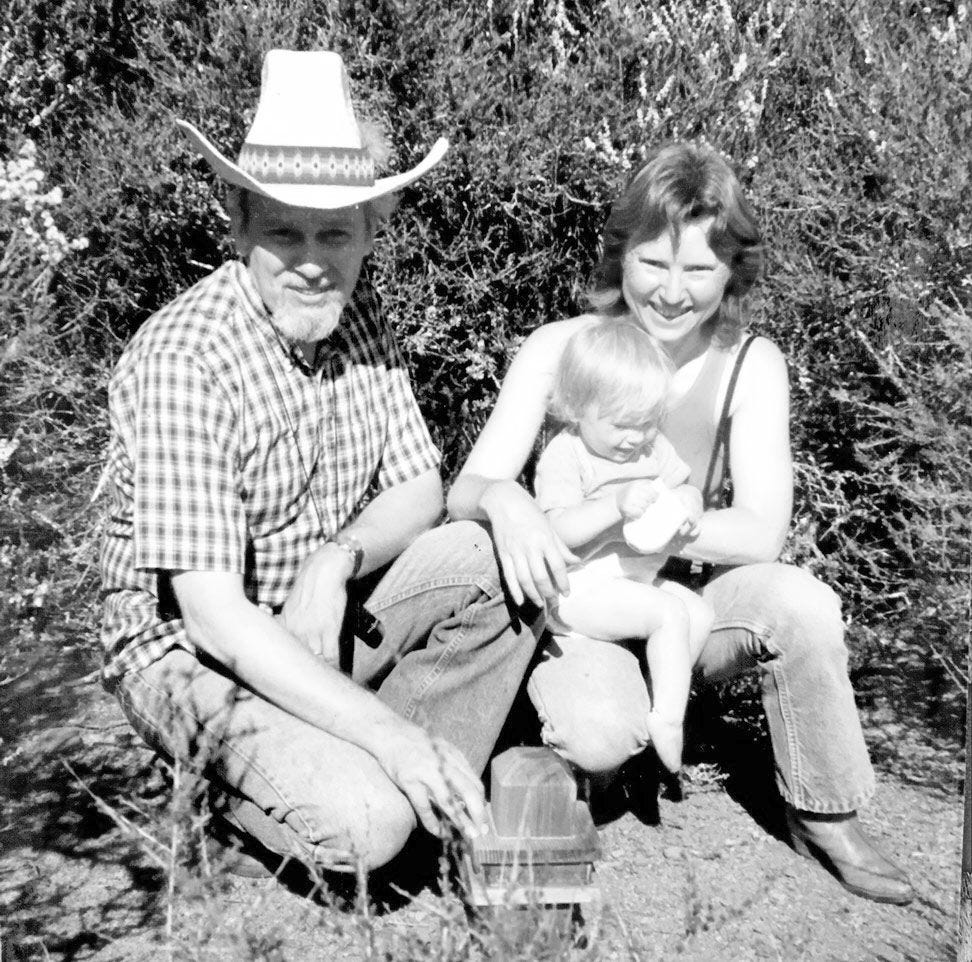

Jerre Sears and Joyce Black Sears moved to the top of Howell Mountain in 1979, a year before they were married.

“What I hope for our community is for people to understand what the land and forest can do to benefit us,” Sears Jambois said. “I think we often see land that is being unused and think that maybe it’s a shame, how can it be monetized? But that can’t be our ultimate goal at this point. There’s too much at stake with climate change. And in order to keep Napa Valley a grape-growing community, we also have to protect the forest and the watershed and the animals that live here.”

15 months without power

The September 2020 Glass Fire swept through the Black Sears property, “every square inch” of the 420 acres, including the 24 acres of vineyards, Sears Jambois said. The family lost 75% of their cabernet sauvignon vines, about 5 acres, although their 12 acres of zinfandel grapes survived.

“People say vineyards don’t burn, and it didn’t actually catch on fire, but it was the radiant heat from the trees that just cooked the vines,” she said.

Thankfully, the zinfandel vines held up just fine, so there was a grape harvest last year, and there will be one this year.

After the Glass Fire, “I think all of us are really rethinking what it means to live in this area, what our responsibilities are, what our goals are and whether we can continue living here with the threat of fire and PG&E turning off the power,” Sears Jambois said.

They were without power for 15 months, from September 2020 to just a week before Christmas in 2021, and although they had a generator, Sears Jambois said it was challenging and stressful with their three sons, Lucien, Oren and Dashiell, at home.

Before the land was transferred to the LTNC, a botanist came to survey the property. He evaluated the biodiversity of the 117 acres, which are adjacent to the vineyard and their home.

“He was seeing all kinds of plants, both those that bloom after a fire and also wildflowers that you can’t find in other parts of California,” Sears Jambois said. “It was very, very exciting for us. We’ve lived here so long and we see all these plants and know a lot of them, but to have a botanist come out who really knows what he’s talking about, that was wonderful. My kids came and walked with him. He was fantastic.”

The forested property has varied habitats, chiefly Douglas fir and mixed hardwood with madrone and several oak species as well as foothill pine and chamise/chaparral, according to the botanical survey. Nine special-status species were identified, according to a land trust press release. The species included Napa Lomatium, Cobb Mountain Lupine, Napa Checkerbloom and Nodding Harmonia, which are all rare, endemic wildflowers that exist only in Napa and three or four other counties.

Deep roots in Napa County

Joyce Black Sears is the daughter of two San Franciscans who moved to Oakville in 1938 or so. She was born in 1942 and grew up in Oakville, at the base of the Oakville Grade. She went to grade school and high school in the area.

“So she has deep Napa Valley roots, as they say,” Sears Jambois said.

Black Sears met her husband on a Sierra Club backpacking trip.

“My dad was a businessman in San Francisco, and he was in the midst of making life changes,” Sears Jambois said.

The couple bought a 100-acre plus parcel of land on the top of Howell Mountain in Angwin, were married on the property, had a baby, Ashley, and built a home.

“The idea behind their move was really to just get back to nature,” their daughter said. “They just really wanted to have quiet My mom wanted to find a place to live where she couldn’t hear traffic.”

Adjacent to their property was a sick and diseased zinfandel vineyard planted on top of an apple orchard in 1975. The owners, also a San Francisco couple, realized “they were in a little bit over their heads and wanted to sell.” Jerre and Joyce bought the vineyard, and later, when adjacent properties, raw forest land, were for sale, they bought them. Sears Jambois said the land in the 1980s and ’90s was expensive but still affordable, unlike today. Jerre and Joyce realized they didn’t need any more vineyards, “but they really wanted to maintain the surrounding forests.”

In 2004, after 25 years of being vintners, Jerre and Joyce decided it was time to slow down, and when winemaker Ted Lemon left Black Sears after the 2006 vintage, they retired. The next year they hired others to do the farming and sold all of their fruit. Jerre and Joyce talked about selling their ranch as it was becoming too much to manage.

Ashley grew up on the land and loved the wild property, now 460 acres, as much as her parents did. In 2008, she and her fiancée, Chris Jambois, left their careers and lives in Seattle and moved to the Howell Mountain property, even though they had little experience with fine winemaking. Now Ashley and Chris are running the ranch and vineyards and raising their family.

“We have three boys and now live here full-time with my mom,” Sears Jambois said.

Jerre died a few years ago.

Sears Jambois said she and her husband “very much understand farming, but our understanding of farming is that you can’t grow grapes without also maintaining the natural forest surrounding. That’s really an integral part of our farming.”

The forest adds to the beauty of the vineyard and the hawks and owls help with rodent control. Additionally, the family shares their ripe grapes with the bears that come through the vineyard and have built a bear ladder so the bears don’t have to break down the fence. Once the fence is broken, when the deer show up and if it’s spring, they will eat the shoots on the vines.

In the first two years since the Glass Fire, Sears Jambois saw bears come through the vineyard in the spring – unusual, but it may have been because their habitat was burned in the fire. This year, though, the bears came through in late July or early August.

“It was a little early in terms of fruit ripening, but much better than in the spring,” she said.

LTNC celebrates 47 years

According to its website, the Land Trust Napa County “works cooperatively with landowners and our community to protect agricultural land, water resources, wildlife and wildlife corridors, scenic open space, forests, ranches, wildflower meadows and native biodiversity throughout Napa County.”

In its 47 years of existence – it was founded in 1976 -- the LTNC has protected 91,000 acres, more than 17% of Napa County, according to its website. Of the 252 projects in that time:

-156, or 47,034 acres, are under Land Conservation Agreements, where the property stays in private ownership but the LTNC holds the agreement that forbids commercial or residential development;

-21 properties, 26,180 acres, were transferred to state and local agencies, including Fish and Wildlife and State Parks;

-24 properties, making up 18,246 acres, are owned by the land trust.

On the properties it owns, “We pursue active management, including removing invasive plants, restoring native species, protecting wildlife corridors, decreasing erosion, restoring streamside habitat, conducting prescribed burns, forest management and grazing to reduce fuel loads and restore natural values,” according to the LTNC website.

In the wake of the Glass Fire and other wildland fires, Sears Jambois said so many people have differing views on the relationships between nature and fire, between humans and fire and between farming and fire.

“There’s no clear-cut answer as to how we, as humans, deal with this new world we’re living in,” she said, “but one thing that is clear to us is our responsibility to nature and to what we have left in this valley in terms of forest and watershed. The Land Trust of Napa County is an organization that we’ve long admired for their efforts at conservation, working with the community to help ensure for future generations that we don’t lose all of the forest and habitat that we have.”

Dave Stoneberg is an editor and journalist, who has worked for newspapers in both Lake and Napa counties.

Absolutely love this article!! My best to the Black Sears family and their legacy of environmental stewardship on Howell Mt. Can’t help adding that I was Ashley’s 4th grade teacher ❤️

Thanks for another interesting article about our Napa Valley neighbors. Hooray for the Black Sears Jambois family!